In the wake of the Unite the Right rally in 2017—and even more so during the George Floyd protests of 2020—hundreds of Confederate monuments across the country were toppled, removed, or added to the agendas of countless city council meetings. Of course, thousands more remain, spread far and wide below the Mason Dixon line as well as stretching up through the North and as far west as Alaska. But for the cities that did remove these racist statues, the next issue has become: what to do with them? While supporters claim they’re historic pieces of artwork, activists believe that they are symbols of intimidation and remnants of treason against the United States.

“I doubt that most people within their right mind would see [a Confederate statue] as a ‘fabulous piece of art,’” a pro-removal activist, Ashton Woods, said. “The reality is that it is a form of intimidation. It is representative of subjugation, hate, slavery.”

Government officials have tried to grapple with the best course of action for monuments that are symbols of both divisiveness and history, balancing the need to confront America’s past without glorifying it. Do they relocate the statues to a museum, repurpose them into something entirely different, or just destroy them completely?

Here’s what several cities have decided to do with their removed statues.

Melt it down and turn it into art

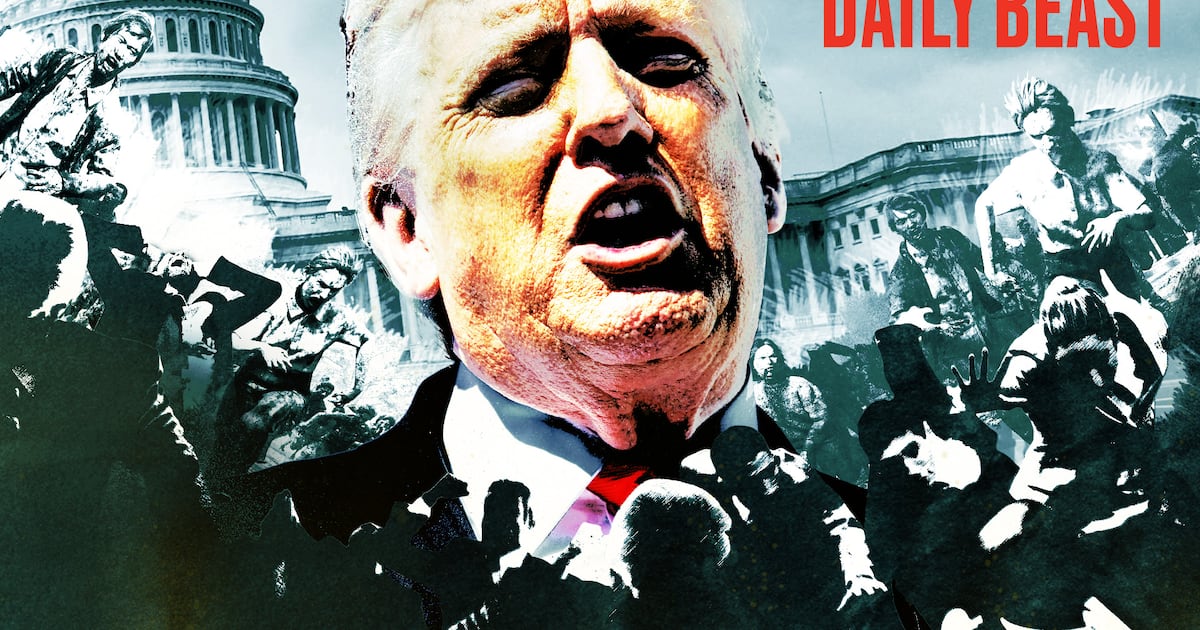

Charlottesville’s decision to remove the city’s Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee statue sparked the deadly Unite the Right Rally in 2017, when white nationalists stormed the University of Virginia and led a violent march throughout the city. It then became the genesis of the recent trend of removing Confederate statues across the country.

The statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee stands behind a crowd of hundreds of white nationalists during the “Unite the Right” rally on Aug. 12, 2017, in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Chip Somodevilla/GettyThe nearly 100-year-old statue was taken down from Market Street Park, formerly Lee Park, in July 2021 and had sat in storage as court battles played out. In December 2021, the Charlottesville City Council unanimously voted to donate the statue to the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, a Black history museum in the area. During the meeting, city council members addressed other proposals for the monument, from exhibiting it at an art museum in California to selling it to an interested rancher in Texas. However, they ultimately settled on the Jefferson School as it was a charity the city had supported in the past, and the institution promised a permanent resolution rather than a temporary move. Council members said they trusted the mission of the school over sending the statue elsewhere for it to be repurposed in a way that the group did not agree to.

The Jefferson School intends to melt the monument down and reconstruct it into artwork to be gifted to the city and put on public display.

“Our aim is not to destroy an object, it’s to transform it,” the heritage center’s executive director Andrea Douglas told Charlottesville Tomorrow. “It’s to use the very raw material of its original making and create something that is more representative of the alleged democratic values of this community, more inclusive of those voices that in 1920 had no ability to engage in the artistic process at all.”

Tour it cross-country as an art exhibit

In June 2020, legislators in Charleston, South Carolina, voted unanimously to boot a statue of former Vice President John C. Calhoun, a white supremacist and major proponent of enslaving Black Americans during the 19th century.

“We have a sense of unity moving forward for racial conciliation and for unity in this city,” Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg said after the vote.

Now, after months in storage, a group of art curators want to temporarily add the statue to an exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. The Post and Courier reported that the exhibit, starting in 2023, will feature Antebellum-era artifacts and artwork borrowed from different cities, along with explanations giving the historical context of each item. The City of Charleston Commission on History recommended in December 2021 to lend the monument to the exhibit, but the decision will ultimately rest with the city council when it rules this month.

A statue of John C. Calhoun is removed from the monument in his honor in Charleston, South Carolina.

Sean Rayford/GettyDuring the commission meeting, Hamza Walker, the director of LAXART—an art museum which is overseeing the exhibition—said he hoped it would lead to a partnership to share and tell history beyond the monument’s return to Charleston.

“We were looking for partners in this exhibition, and it isn’t simply a question of just borrowing the object as a formal loan and that’s the end of the relationship,” he said.

He said the statue would be treated like “any other work of art.”

Destroy it altogether

After racial justice protests erupted across the country following George Floyd’s death, many North Carolina cities removed Confederate statues and simply put them in storage while they grappled with what to do. Asheville went a step further, deciding to permanently destroy a monument dedicated to former white nationalist Gov. Zebulon Vance that had stood for more than 120 years at a city center where enslaved Africans were auctioned off.

In a February 2021 document from the Joint Vance Monument Taskforce, the group noted that the monument was constructed as an obelisk, not even in Vance’s likeness.

“The Egyptians used the obelisk to commemorate the dead, represent their kings, and honor their gods,” the document read. “The obelisk in Asheville could tell the real history in Asheville by…tell[ing] the truth about Vance…illustrat[ing] slaves sold on the site…[and] illustrat[ing] through artwork the accomplishments, contributions, culture, and history of African Americans in Asheville.”

The task force added that repurposing the statue could help heal, unite, and educate the community. But ultimately the Asheville city council decided in a 6-1 vote in March 2021 to remove it and have it demolished due to concerns about public safety and how it could impact tourism, the Charlotte Observer reported. The city will have to approve of the way a third-party contractor demolishes and discards the monument, and it won’t be able to be broken up, sold off, or used again in any way.

Replace it with a better one

A Confederate monument in Decatur, Georgia, was removed from the front of the Dekalb County Courthouse in June 2020. Though the obelisk monument has been put in storage for the time being, the city has decided that a new statue of the late civil rights activist Rep. John Lewis (D-GA) will take its place.

The court decided that the statue “was a public nuisance and saw that it needed to be removed,” Dekalb County Commissioner Mereda Johnson told The Daily Beast.

“That statue represented hatred, bigotry, racism, all of the negative aspects that Dekalb County government and its citizens do not embrace,” she added. “That was one of our initial reasons to want the removal—with everything happening in the country. I think that with the last administration, it was open season to openly discriminate.”

Johnson said plans for the John Lewis statue were already in the works but the city saw an opportunity when the Confederate monument came down.

“We have not gotten much opposition at all from the announcement of placing the John Lewis statue at that location. It’s been overwhelmingly positive feedback,” she said. “Overall, people have just really embraced it and celebrated. That was our intent.”

The new statue isn’t expected to be completed until at least 2024. The fate of the Confederate monument has not yet been decided but Johnson said she couldn’t care less what happens to it.

Put it on display… in a Black history museum

In 1908, a chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected the Spirit of the Confederacy statue in a Houston park for “all heroes of the south who fought for the principles of states rights.” After ongoing protests against racism and police brutality, a Houston task force made up of historians and community leaders decided to remove the statue of a male angel bearing a sword in June 2020. Rather than destroy it, the group received a grant from the Houston Endowment to permanently relocate it to the Houston Museum of African American Culture in August 2020. The Black history museum, which boasts a mission “to collect, conserve, explore, interpret, and exhibit the material and intellectual culture of Africans and African Americans… for current and future generations,” is the first in the country to showcase a Confederate statue.

The museum’s executive director, John Guess, said the statue’s installation was “something special.”

“This is the only place that this is going on in the country,” he said as the statue was being relocated to the museum. “If we can have this voice, to have this conversation… it’s not overwhelming, but it’s something.”

“As an educational space, we wanted people to think about it and engage with it,” he told Hyperallergic. “Healing comes from taking control of negatively impactful symbols and turning them into teaching opportunities to help ensure they never have power again.”

Sell it off to some Texan’s fancy golf club

Unfortunately, not every Confederate monument can be repurposed for good. ABC News reported that a 1935 statue of Robert E. Lee was removed from a Dallas park in 2017 and later snapped up at an auction by a Texas golf resort.

“I, for one, think the statue needs to be destroyed, but the city of Dallas thought that it could probably, most likely make a profit off of it,” Houston Black Lives Matter chapter lead organizer Ashton Woods told The Daily Beast, adding that Confederate statues are a “physical representation” of institutional racism that still persists.

The private Lajitas Golf Resort on the Mexico border in Terlingua bought the statue in 2019, according to ABC News. The resort’s manager, Scott Beasley, reportedly said that the statue was “a fabulous piece of art.”

“I highly doubt that anybody who looks like me would see it that way,” Woods countered. “If [people] can’t get rid of a simple Confederate monument, what else will they not be able to handle?

“These are the same people who were OK with children being separated from their families at the border. These are the same people who were OK with putting children of various ages and young adults of various ages in facilities that were deplorable. These are the same people who want to build border walls that fall apart. These are the same people who peddle hate, Naziism, white nationalism, white supremacy, you name it,” Woods continued. “So, it says to me that that is a form of intimidation.”

Neither Scott Beasley nor the Lajitas Golf Resort returned The Daily Beast’s request for comment.

Round them all up and let Black historians decide what to do

The Black History Museum and Cultural Center in Richmond has agreed to take ownership of multiple Confederate monuments from around Virginia and D.C.-areas. The most notorious, the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, has been a central figure in the fight against Confederate memorabilia. The statue, along with other monuments dedicated to J.E.B. Stuart, Stonewall Jackson, Jefferson Davis, Matthew Fontaine Maury, Joseph Bryan, Fitzhugh Lee, Confederate Soldier and Sailors, and a ceremonial cannon will be sent to the museum.

“What the museum has done is agreed to accept ownership temporarily until [the city] figure[s] out where all of the pieces go permanently,” said Greg Werkheiser, whose law firm Cultural Heritage Partners, PLLC is overseeing the relocation. “I’m not aware of any community in the United States that has a larger collection of monuments that have been removed.”

Circle Neighbors, a group of homeowners in Richmond, hired the law firm to remove the Robert E. Lee statue from their residential area after they said it “contradicted the values of the neighborhood” and conveyed “a false and harmful historical narrative.”

Black Lives Matter activists occupy the traffic circle underneath the statue of Confederate Gen. Robert Lee in Richmond, Virginia.

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via GettyWerkheiser explained to The Daily Beast that it was a lengthy process to determine where the monuments would go. Initially, the city wanted to consider everyone’s input about the monuments’ futures, but Gov. Ralph Northam decided the best option would be to display the monuments with an appropriate context. Descendants of Lee tried to challenge the statue’s removal, arguing that it would cause them emotional distress, while some residents living near the statue claimed that its removal would negatively impact their home values.

“From the museum’s perspective, there’s a little bit of cosmic poetry that flows from the idea that an African American history museum would be the one to ultimately” decide how to tell the story surrounding the Confederate monuments, he said.

“Although they were put up by white people to continue to send symbols of messages of oppression, the oppression was obviously directed at certain populations. It makes sense now at a modern time to have that population at the table, as opposed to just a conversation between city and state bureaucrats and institutions.”

Werkheiser pointed out that the museum will only hold onto the monuments temporarily. “It doesn’t mean that you’ll be able to, a year from now, buy a ticket to the Black history museum and see a ‘Losers Park’ or whatever it is. It may very well be the case that one or two of the most iconic pieces end up there. It may be that others go elsewhere. But to have the museum in charge of that discussion… is really kind of meaningful,” he said.

He added the museum also wants to be part of “a more thoughtful and directed conversation” about why these monuments became a focus for people in the post-George Floyd era.

“And so, to the extent that the conversation around the monuments is a gateway to a much more important conversation about policy and current conditions of life for Black and brown people in this country,” Werkheiser said.