When the entire Marion, Kansas, police department raided the small city’s only newsroom last week it drew national condemnation. At least 34 news organizations, including The New York Times, Associated Press, and CNN decried the attack on the Marion County Record as an attack on freedom of the press and the First Amendment.

Thankfully, newsroom raids are rare and constitutionally suspect in the U.S. But the alarming reality is that while newsroom raids may be rare in America, police surveillance of journalists is not.

From fake social media accounts to counter-terrorism databases, law enforcement agencies frequently use the sprawling surveillance systems that define American policing to track the press. And unlike with newsroom raids, the courts often never know.

Very few judges would sign off on the type of raid that took place in Marion, which came after a local resident complained that the paper violated Kansas’ identity theft law by obtaining records of her past DUI citation. Rather than voluntarily requesting the records, or even serving the paper a subpoena, police requested and—a judge approved—a full-fledged warrant, authorizing officers to knock down the door and take the paper’s files, computers, and other records.

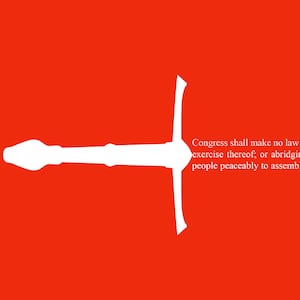

Such an approach would be considered heavy-handed with a lot of businesses, especially for such a far-fetched identity theft allegation, but it violates federal law when targeted at a newspaper. That’s because of the obscure Privacy Protection Act of 1980, which prohibits police from searching newsrooms without first serving a subpoena and exhausting all other options. The press freedom measure was enacted swiftly after the Supreme court ruled that it was constitutional for police to raid the Stanford Daily, looking for photos of a political demonstration.

On its face, the same federal law that bans newspaper raids should also outlaw electronic surveillance of journalists, but the reality is quite different.

The Privacy Protection Act only applies to police uses of a warrant, but much of modern surveillance completely circumvents the courts—not to mention public scrutiny. Not only can police take information from countless social media platforms without a warrant, but there is a booming business from data brokers who sell police our most intimate information. And, alarmingly, when police use public funds to purchase our private information, instead of getting a warrant, courts have held that the Fourth Amendment and many privacy laws simply don’t apply.

Several police departments have been especially eager to target these tactics at Black reporters. In 2018, an ACLU lawsuit against the Memphis Police Department revealed that officers had created fake Facebook accounts to “friend” Black reporters and activists, tricking surveillance targets to share private posts and personal information. But because officers tricked reporters to provide information, rather than serving a court order on Facebook, the Privacy Protection Act never applied.

Ultimately, the ACLU was able to prevail against the Memphis spy tactics, but such an outcome was hardly assured.

Police are also eager to use these same tactics against those reporters who are critical of police themselves.

Some of the most chilling examples come from the Atlanta-based opposition to the sprawling police training facility referred to by critics as “Cop City”—whose construction became a lightning rod for those fighting continued expansion and militarization of police. There, journalists were arrested, intimidated, and surveilled. In one case, officers tracked a reporter as they left the area near protests, even though the reporter’s work was clearly protected by law.

Records from Cop City also show how homeland security officials compiled information from local reporters as part of their surveillance dossiers on activists. Officers once again turned to social media to track reporters like the Atlanta Community Press Collective. And once again, since police could get this information without a warrant, federal journalism protections never kicked into place.

Where there are protests, police surveillance of journalists quickly follows.

In 2020, when the historic protests against George Floyd’s murder upended Minneapolis, Minnesota State Patrol officers began compiling detailed dossiers on journalists. The interagency consortium, named Operation Safety Net, scoured social media, phone records, and biometric data to track those reporting on protests. Alarmingly, the effort continued long after Derek Chauvin’s trial concluded, despite public reassurances to the contrary.

And it’s not just state and local police departments that abuse their surveillance systems against the press. In 2021, Yahoo News detailed a secretive unit of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) that used counterterrorism databases to track 20 journalists. And as with so many of these scandals, none of the officers that spied on journalists were ever charged.

Perhaps most alarming of all is the fact that these are just the examples we know about.

Oftentimes, we only learn about journalists being surveilled by accident, years after the fact. So while journalists are right to be outraged by what happened in Kansas, right to push back against these sorts of abusive tactics, they simply are missing the bigger story.

We need to mobilize just as strongly against the growing electronic surveillance targeting newsrooms. And it is long past time that Congress act to update federal law to protect journalists online, and not just in the office.