John Didion and John Wilbur never made the Pro Football Hall of Fame but they joined an even more select group in 2013. Didion and Wilbur’s deaths shortly before Christmas mean 23 former players suing the National Football League have died in this past year alone.

The NFL and players settled this summer for $765 million, which will be paid out according to injury, next year. But even a slice of the almost-billion-dollar pie is not enough for some retired players: ex-quarterback Craig Morton opted out of the settlement so he could sue the NFL for failing to protect players.

While Morton and other retired players like Brett Favre (who suffers from memory lapses and claims he forgot his daughter played soccer) are looking for answers to their troubles, what’s clear is that a lifetime of head trauma results in a clinical syndrome that varies from player to player.

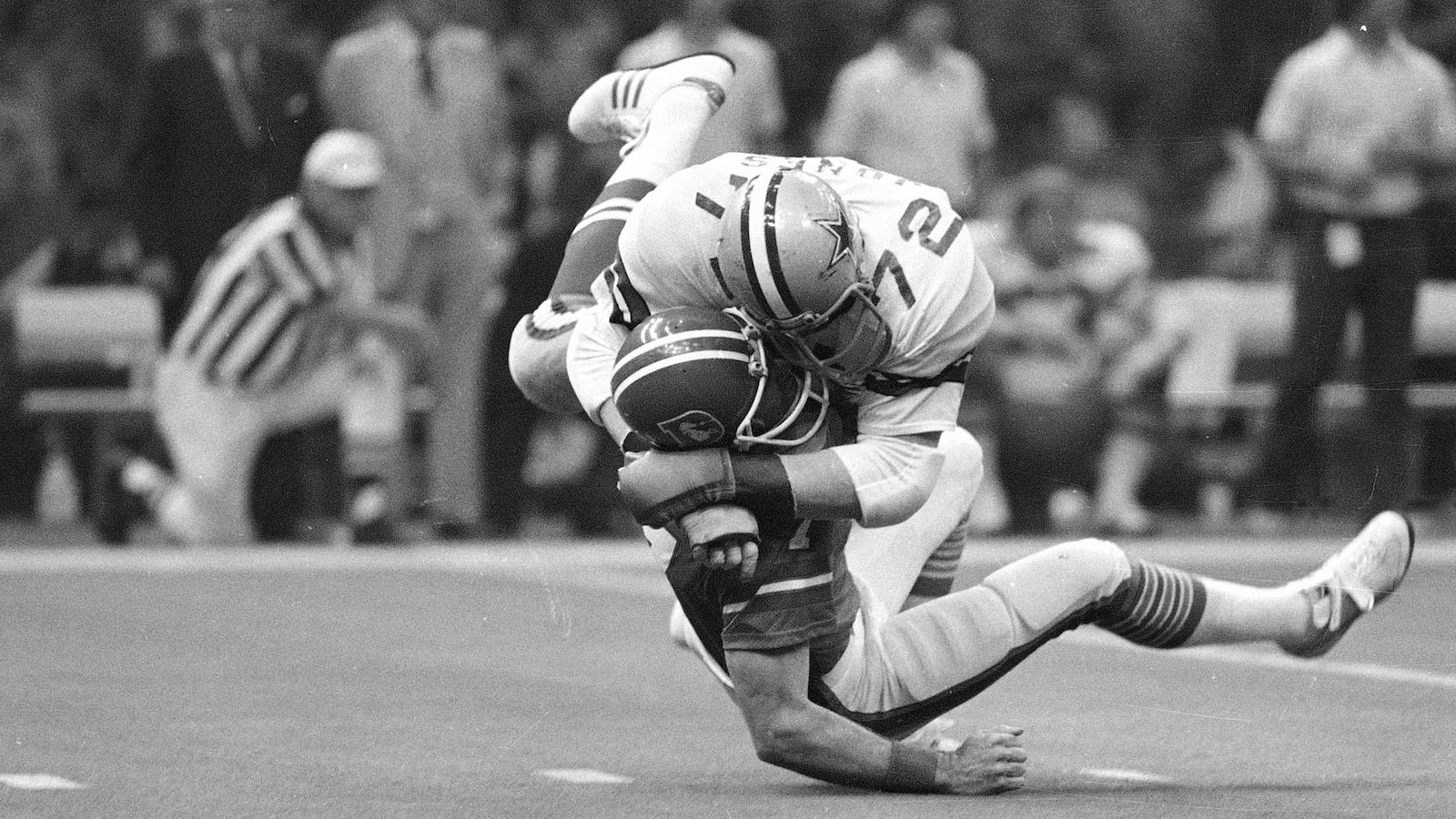

A crushing impact directly to the head is not required to cause brain injury. Any time a player sustains a jolt from a blow to the head, neck, or upper body, the brain suffers some degree of trauma. After all, the brain is as soft as gelatin, and the body can only do so much to protect it. Such aggressive hits can result in impaired brain function, fuzzy thinking, disorientation, and symptoms such as headache, dizziness, or nausea – in other words, a concussion.

Formally, the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology defines concussion as “a trauma-induced alteration in mental status that may or may not involve loss of consciousness.” Concussions are particularly tricky to identify because signs of the injury can appear anywhere from minutes to days after the insult, and symptoms can disappear without warning. Remember, it is also possible for a player to have a concussion even if he or she does not lose consciousness.

In today’s era of athletic competition where money, fame, and whole industries are on the line, admitting pain or discomfort suggests weakness and can have severe consequences for the player and the team. Thus, players often rack up multiple concussions throughout their career. Data suggests that head injuries are significantly underreported by players, who often dismiss concussive symptoms. These are all direct contributors to a robust concussion culture in contact-heavy sports like football, hockey, and even soccer. Scientists have shown that the impact of repetitive concussions is cumulative--one builds on the other. Even sub-concussive hits increase an athlete’s risk of developing long-term neuropsychological problems.

The effects of repeated brain trauma are classified as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), where brain and mental injuries increase in severity and duration with additional hits. An encephalopathy is a disorder of the brain, so CTE refers to accumulation of separate traumatic incidents over time that result in brain disease. People suffering from CTE – which can only be definitively diagnosed with a post-mortem analysis of the brain – experience significant problems with thinking, behavior, mood, and motor function.

CTE is not the only neurodegenerative disease linked to head impacts though. Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease), have also been linked to head injuries. Additionally, researchers are making great progress in understanding the cause-effect relationship between brain injury and depression, bi-polar disorder, and suicide. The general idea is that physical disruption of the brain can upset normal processes and also kickstart disease-causing progressions, such as buildup of proteins in specific parts of the brain.

In the controversial settlement between the NFL and retired players, those with Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease could receive up to $3 million. The families of players who committed suicide and received a post-mortem diagnosis of CTE are eligible for as much as $4 million, and up to $5 million was offered to players with ALS.

If it is determined that the league intentionally ignored evidence of the damaging effects of concussions, then maybe the NFL does deserve a sizeable share of the blame for retired athletes’ problems. However, these head injuries began long before professional play. An estimated 10 percent of college and 20 percent of high school football players sustain brain injuries each season. This means retired professional athletes experienced hits early and often, for upwards of 20 years, and the hits only got harder as they moved to higher levels of competition.

If we are going to ask ourselves what is killing concussed NFL players and other professional athletes, we have to be willing to discuss the dangers of playing contact sports from an early age. We should be compelled to explore what aspect of sports culture motivates a player to ignore symptoms like dizziness and nausea after a jarring tackle. When Jadeveon Clowney returned to the sideline after laying out a Michigan runningback at this year’s Outback Bowl, it is highly unlikely he received a word of caution about tackling so fiercely. Clowney was heartily congratulated by his teammates, and then saw his tackle repeatedly on highlight reels. Indeed, he is now projected to go in the top five of the 2014 NFL draft. Yes, Clowney’s was an effective hit, but the question remains – do these players know what could be happening to their bodies?