There’s never been a book like Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington, which documents over a half-century of the gay political and social scenes of the U.S. capital city.

But James Kirchick—a columnist for Tablet, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, and a past Daily Beast contributor—has written an exhaustive history of the joys, torments, and political advocacy of D.C.’s gay community spanning from World War II until the end of the 20th century.

Kirchick spoke with The Daily Beast’s senior opinion editor Anthony L. Fisher about the book, the stunning scoops he uncovered through archival research, and how the First Amendment gave gay advocates their strongest weapon to fight for their civil rights.

This interview has been edited for style, clarity, and length.

Squarely in the middle of the book, you've got a line that completely jumped out at me, which was that “the greatest fear of the American male is that he will be born homosexual.”

Can you talk a little bit about that and what that might have had to do with writing the book?

Yeah, it comes in the context of talking about Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, so I’m not sure if I would say that’s still true. But it’s written in that historical period, and I think it was true.

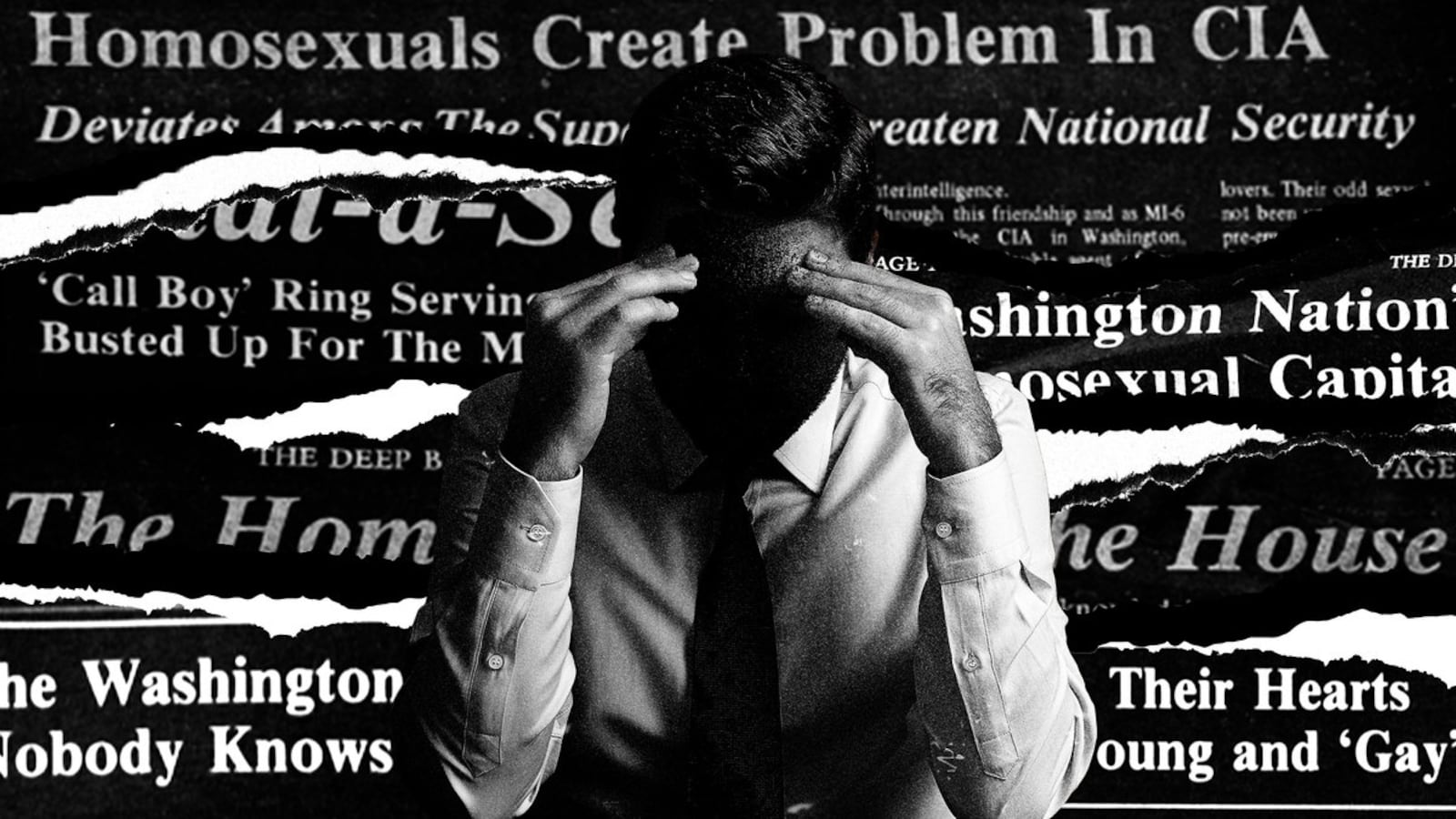

Certainly during the period of time I cover in the book—from World War II to the end of the century—the worst thing you could be was gay. It was condemned by all of organized religion. It was deemed a mental condition by the psychiatric establishment. It was criminalized. And it was socially taboo. Even being suspected of being gay could ruin a person.

When you look at a figure like [the late former Rep.] Jack Kemp—just the rumor that stuck to him with no real evidence at all—it was always there lurking in the shadows and it sounds like it stopped him from becoming Reagan's vice presidential nominee in 1980.

And Kemp was a former NFL player.

And he lived a vigorous heterosexual life by all accounts. But just that one rumor stuck and it really held him back politically.

You're a child of the ’80s and ’90s, did that kind of sentiment inspire you to write this book?

Until I was doing the research, I don't think I really realized how profound and extensive the fear and loathing of homosexuality was. And how gripped by this fear our society was, particularly in Washington. I mean, that's where it was the deadliest sin.

What made you zero in on the gay history of Washington? Why that city specifically?

Washington is a city of secrets, as the title would suggest, and there's no secret that was more dangerous than this one. When you're a journalist, you're trying to find something new to say and this seemed like a really good way to tell a story about Washington that hadn't been told before.

There’s been lots of books about the Red Scare and Cold War Washington in terms of the fear of communism, but very little has been done on this theme.

How homophobia is like antisemitism

This book is more than just a compilation of previously reported history, you actually uncovered some pretty big scoops.

The archival research generated the best finds, and the biggest scoop was probably this sort of crazy “Reagan gay scandal” in 1980 that I uncovered.

There was a fear that Ronald Reagan was being controlled by a right-wing gay cabal, which was brought to the attention of Ben Bradlee at The Washington Post in the summer of 1980, right before the Republican convention. The Post investigated it, and Bob Woodward was one of the reporters. They did uncover the existence of several gay men who were basically Reagan’s PR managers from the end of his governorship until he was president.

The Post didn't find the existence of any sort of nefarious conspiracy, but it’s an example of how people thought at the time. If you had gay people in any sort of proximity to a politician, that automatically, was indication of a conspiracy, yeah.

It's very similar to antisemitism actually. Some people see a couple Jews and all of a sudden it's some vast conspiracy. People used to think about gays the same way.

I wrote an essay for The New York Times Magazine on the long history of homophobia as a conspiracy theory, which I traced back to this scandal in Wilhelmine Germany in the early 20th century, where there was an alleged ring of gay advisers around Kaiser Wilhelm II. There was a “camarilla of pederasts” around the Kaiser, this newspaper wrote. And the controversy went on for years.

But then it gets updated during the Cold War, and the “velvet mafia” is a more modern take on that.

Another big find in my research was the existence of this aide who worked for Lyndon Johnson, Bob Waldron, whose 1,000-page FBI file I was able to get declassified. He was a very close adviser—almost a substitute son—to LBJ, who tried to bring him on staff when he was moving into the White House. They do a background check, they find out he's gay. It's a really sad, tragic story. Not even [LBJ biographer] Robert Caro knew about this.

I got a couple seconds of Nixon tape where he's talking about various people being gay. It had been redacted while those people were still alive.

There's one line where he refers to Allen Drury [author of the seminal 1959 D.C.-set novel Advise and Consent] as a homosexual, which I'd always suspected. One thing I discovered writing this book is that Advise and Consent was a very revolutionary book in its portrayal of a gay subject. It might be the first work of mainstream American fiction to have a gay hero. And everyone around [the hero] is using homophobia to basically destroy him—and he kills himself.

But the issue of his homosexuality, while tragic, it's not seen as a character fault. Which is very unusual. The film adaptation changes that, and I write about how Drury was very unhappy with the movie version. He was on the record about that. No one really dug into why.

And you write in Secret City about a real-life D.C. tragedy that was a major inspiration for Advise and Consent.

Lester Hunt was a Democratic senator from Wyoming whose son was arrested for solicitation in Lafayette Square—which used to be the main gay cruising ground in Washington. And that tells you a lot about gay Washington, that the main hangout was right across the street from the White House.

After his arrest, two of [Sen. Joseph] McCarthy's allies in the Senate tried to use this to pressure him to resign his seat. And Hunt ends up killing himself. It's the first and only suicide in the halls of Congress. And it was one of several inspirations for Advise and Consent.

Going back to conspiracy theories about homophobia, it feels like there’s a modern-day version of this happening right now with the whole “groomer” panic. And in Secret City, you cite Joe McCarthy’s quote, “If you’re against me, you’ve got to either be a communist or a cocksucker.”

That sounds a lot like the people who rant about “Cultural Marxism” and “groomers” in schools. Do you see the parallels between the Red Scare and the Lavender Scare with what’s happening in political discourse right now?

I’ve become, in general, more skeptical of moral panics on the left or the right. Particularly with this age of social media, it’s easy for people to get swept up into something with very little evidence, that then gets blown out of proportion. That’s ultimately what the lavender scare was. It was a complete and utter moral panic, more so than the Red Scare because that was at least based on some truth. There were some communists in the government.

Alger Hiss seated and smoking a pipe, 1965.

Courtesy of Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLAAlger Hiss, who I write about extensively, was a Soviet spy. And the liberal reaction—which was to immediately defend Hiss—gave McCarthy the kind of ammunition he needed. Cause he could point to them and say, ‘A-ha, look at these liberal elites, they're protecting communists.’

But with the Lavender Scare, there was absolutely no basis whatsoever. There was never any evidence of a single gay person turning over sensitive information because they were gay. There was just a complete and utter moral panic. It’s made me more hesitant of these waves of hysteria that we very easily get swept into.

And yes, this grooming discourse is definitely an example of that. I mean sure. Are there examples on Libs of TikTok that are disturbing? Yeah. I'm not going to deny that. But is this being taught in every single school across the country? That's what we're being made to think. And that's obviously bonkers.

Gay rights have come incredibly far almost seven decades since McCarthyism, and yet this kind of conspiracy-mindedness about homosexuality persists.

The idea that people can make other people gay. Yes. That persists.

And it’s all about the children.

Right, and that goes back to the McCarthy period, when gays were supposedly pedophiles. We see these waves of gay visibility, followed by a backlash reaction.

After World War II was sort of a national coming-out moment. You have Truman Capote and Gore Vidal publishing their novels all in the same month in 1948, which was right around the time the Kinsey Report, which was shocking to everyone. “Oh my God, 10 percent of the country is gay. This is crazy!” And that leads to a backlash.

Then you have Stonewall in 1969 and gay lib starting in the ’70s. A couple of years later, you have Anita Bryant and the Save Our Children campaign and the rise of the Christian evangelical right that sweeps Reagan into power.

Then the ’90s, you have Ellen, you have gay people with increased cultural visibility. You have Bill Clinton welcoming gay people into his administration.

That’s followed in the 2000s, [when Republicans pushed] for a federal marriage amendment and the anti-gay backlash around that. There was a Gallup poll last year that showed the number of self-identified LGBTQ+ people doubling over the past decade. I think that’s also sparked a backlash.

Gayness as a national security threat

If I recall correctly, when writing about the Lavender Scare you said to be suspected of homosexuality literally was more of an indictment than to be suspected of being a communist or a fascist.

I think we can look at Whittaker Chambers as an example of that. He and several other leading conservative figures were ex-communists. You could be an ex-communist, you could come out (so to speak) and renounce your communism. But Chambers could not come out as a homosexual. No one was defending gay people, as there were people who were willing to defend—at least on Fifth Amendment grounds—communists.

There was no one willing to do that for gay people. Even the ACLU! Not only was the ACLUE slow to defend gay people, the chief council of the ACLU, Morris Ernst, was the one leading this campaign against David Walsh, the senator associated in 1942 with the “Gay Nazi Brothel” scandal in Brooklyn. The [then] liberal New York Post and the general counsel for the ACLU were both pushing this campaign to out an isolationist, anti-FDR Senator. And it was because he was gay.

This isn’t to indict liberals, everyone was willing to use homophobia as a weapon back in this period of time. We use the term “ally” a lot. No one was an ally of gay people in the 1940s. Not even the people that you would expect to be.

You wrote about how JFK’s lifelong best friend was a gay man. President Kennedy seemed to be completely comfortable with openly gay people in his private life. But did he do anything to advance gay rights?

He didn’t. And this is a story of several of our presidents.

FDR was very firm in trying to defend his Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, whom enemies of his administration were trying to get fired because he was gay. President Roosevelt was very loyal to him and went to the mat to defend him for years, but ultimately dropped him. FDR policy-wise was not defending gay people—he was involved in purging them when he was an Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1919.

Secretary Cordell Hull, left, and Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles, right. arriving at the White House in 1938.

Courtesy the Library of CongressSame with JFK, who may have been quite ahead of his time as a heterosexual man in terms of his comfort level around gay men. But the policies of the JFK administration were no different from those of the Eisenhower administration or any other. They were purging gay people left and right.

Using the First Amendment to advance gay rights

That’s interesting, because JFK was one of the first presidents to support the civil rights movement. But he didn’t include gay people in that.

No, no one did. It was unfathomable that that would even be thought of. I write about Frank Kameny, who was the leader of the Mattachine Society (an early gay rights organization).

Kameny was the first person who was fired by the government to challenge his firing. He was an astronomer, a PhD from Harvard, who worked for the Army map service—which is now the Geospatial Intelligence Agency. He was really the first person to come out of the closet in America and say: “You know what? Yes, I am a homosexual, but that doesn't mean that I cannot serve my country.”

And he waged a decades-long campaign to restore his job, basically while living in poverty. His papers are at the Library of Congress, you can read them, and he’s an extremely well-written and thoughtful person. All his letters [to the government and elected officials] appeal to the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. These are the arguments that, decades later, the gay rights movement would use successfully. But he’s doing it as this one-man struggle against the entire federal government. He organized the first [gay rights] picket outside the White House in 1965 and later, pickets outside other government agencies.

No one answers his letters, though they occasionally write back and say, “You're filthy. You're disgusting.”

Kameny’s long fight for gay rights wouldn’t have been possible without the First Amendment.

Absolutely.

Which, again, is another thing that ties to today’s politics, as so many people believe that “social justice” and the First Amendment are in conflict with each other. But without the First Amendment, it would have been impossible to wage these protests—while supporting ideas that were wildly unpopular with most Americans.

Yes. They were extremely unpopular. It’s actually hard to think of a more unpopular cause than advocating on behalf of “sexual deviance.”

But Kameny was ultimately successful.

Absolutely. Yeah. Look at the world we live in today. We owe a lot to him.

And the Mattachine Society itself is a fascinating and under-acknowledged part of American political history.

When they had their first meeting at the Hay-Adams in Room 120 in August, 1961, it was surveilled by the FBI. And the Metropolitan Police Department had an informant inside who—by the way—some of the men recognized because he was the same undercover officer they sent to entrap gay men in public bathrooms and parks. Sort of clumsy on [the MPD’s] part.

But this meeting should rank up there with the Stonewall uprising in 1969. It’s not as sexy, a bunch of white men in coats and ties drinking coffee in a hotel room, but it was impactful [for gay rights]. They articulated the intellectual basis for gay rights.

And having a protest outside the White House—all these men and women dressed in business attire—[showed Americans] that gays don’t look like pedophiles or criminals. And it was modeled very much on the African American civil rights movement—respectability politics.

Just how bad was Reagan on gay issues?

Let’s talk about Reagan for a bit. I’m not sure how you politically identify these days…

Center. Maybe center-right.

But you definitely have had some certain conservative leanings over the years.

Sure.

And yet you spare no punches whatsoever on Reagan’s handling of gay civil rights issues and the AIDS epidemic. Just how bad was he on both?

Well, on civil rights—in 1978 he stood up against a measure in California to bar gay people from serving as public school teachers.

So he wasn’t governor anymore?

No, it was in between when he was governor and when he was about to announce his presidential campaign. So there was some risk in doing this. He could have just stayed silent.

And why did he do it?

The case was made to him by a left-wing gay activist named David Mixner that this would lead to chaos in the schools—as students would lodge baseless accusations of homosexuality against their teachers. It would lead to anarchy. It would lead to lawsuits. It would lead to more regulations.

And this was very appealing to Reagan because when he was governor, he had stood up to student radicals on the Berkeley campus. So the argument was made to him from a conservative perspective that this was a violation of individual rights. It was a violation of privacy. And Reagan came out against it a week before [the vote] and he almost single-handedly defeated it. He deserves credit for that.

But then, obviously, his policy on AIDS was terrible. He didn’t even mention the word until 1985, in his second term, four years after the disease was identified.

And you found in his presidential archives evidence that he basically erased his and Nancy’s friendship with [the late actor] Rock Hudson.

I found this draft of the statement that he and Nancy released on Rock Hudson’s death. I remember thinking, “Wow, this is really terrible.” Because it’s in his own handwriting. He’s crossing out—very specifically— any sort of [affection for Hudson]. He crossed out the words “profoundly saddened,” as if the public would care that he said “profoundly saddened.”

You have to understand that Rock Hudson was really the first celebrity to die of AIDS. That’s what put AIDS on the front pages in a way that it hadn’t before. He was a matinee idol, this very handsome leading man. He never officially came out, but when he acknowledged he had AIDS, he effectively came out as gay. That kind of confirmed it.

That’s another thing I discovered while writing this book—it wasn't just that they were afraid of the Christian right. The Reagans actually feared that the president would be perceived as gay himself, because he had a Hollywood background.

I’m curious about a narrative choice of yours in telling this story. Obviously the Reagan era gets a huge section of the book, followed by a short one on the George H.W. Bush years, and an even shorter one on the Bill Clinton years. And then the book ends.

It feels like there a lot more to tell about “Gay D.C.” during both of those presidencies—as well as George W. Bush’s and maybe even Barack Obama’s—when gays were finally allowed to be out and serve in the military. Why did you essentially cut the narrative in the mid-1990s?

I decided that this would be a book about the era when the secrecy of homosexuality was the greatest fear in Washington. And that really exists from World War II—when homosexuality goes from being a sin to a national security threat. And that's because America enters the world stage as a global superpower and needs to develop security apparatus, national security states, and a bureaucratic system for managing secrets.

Take the Sumner Welles case. If that had happened before World War II, I don’t think it would’ve been much of a scandal. They wouldn’t have been able to make the argument that he was blackmailable [for being gay]. I don’t think FDR would've been forced to do anything. And the first outing—of Sen. David Walsh—doesn’t occur until 1942. Clearly there were gay people in governments before those two incidents but it didn’t become scandalous behavior until World War II. And I think that’s meaningful.

Then in 1995, it’s the end of the Cold War. And Bill Clinton lifts the ban on gay people getting security clearances. To me, those seemed like the proper bookends for this book.

Obviously gay history goes on and there are other debates, but it’s not secret anymore. It’s not enforced by the government as being a secret. There’s still the closet. There’s still outing. Outing, of course, becomes a huge [right-wing] phenomenon in the early 2000s during the Federal Marriage Amendment debate. And you have all these Republican staffers being outed, and [Republican] Sen. Larry Craig, and all that. I just felt like this book was long enough as it is and didn’t need to go on any longer. So I decided to end it in 1995.