For all of their obvious populism—the ootsy-cutesy singalongs, the exhortations to love everyone and everything—the Beatles, in their most beat-loving, insectoid hearts, were purveyors of oddities. Not to the degree of a Frank Zappa or a Syd Barrett, but they loved getting their weird on, going back to John Lennon’s youthful days as a Goon Show nut who liked nothing more than drawing figures copulating in the margins of his school books, then making his classmates giggle.

Sometimes Beatles oddness took the form of early covers, especially in the early days—a show tune like “Till There Was You,” a girl-group number like “Boys,” pronouns and gender notions be damned. This put them far ahead of their time, and it also set them up for sonic experimentation that no one was yet dabbling in—Revolver and Sgt. Pepper, obviously. Paul McCartney has cited 1970 B-side “You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)”—the official cut a Beatles nut is most unlikely to know—as his all-time fave by the band, precisely because of the spirit it invokes, a mad hatter’s call of We Will Not Be Hemmed In.

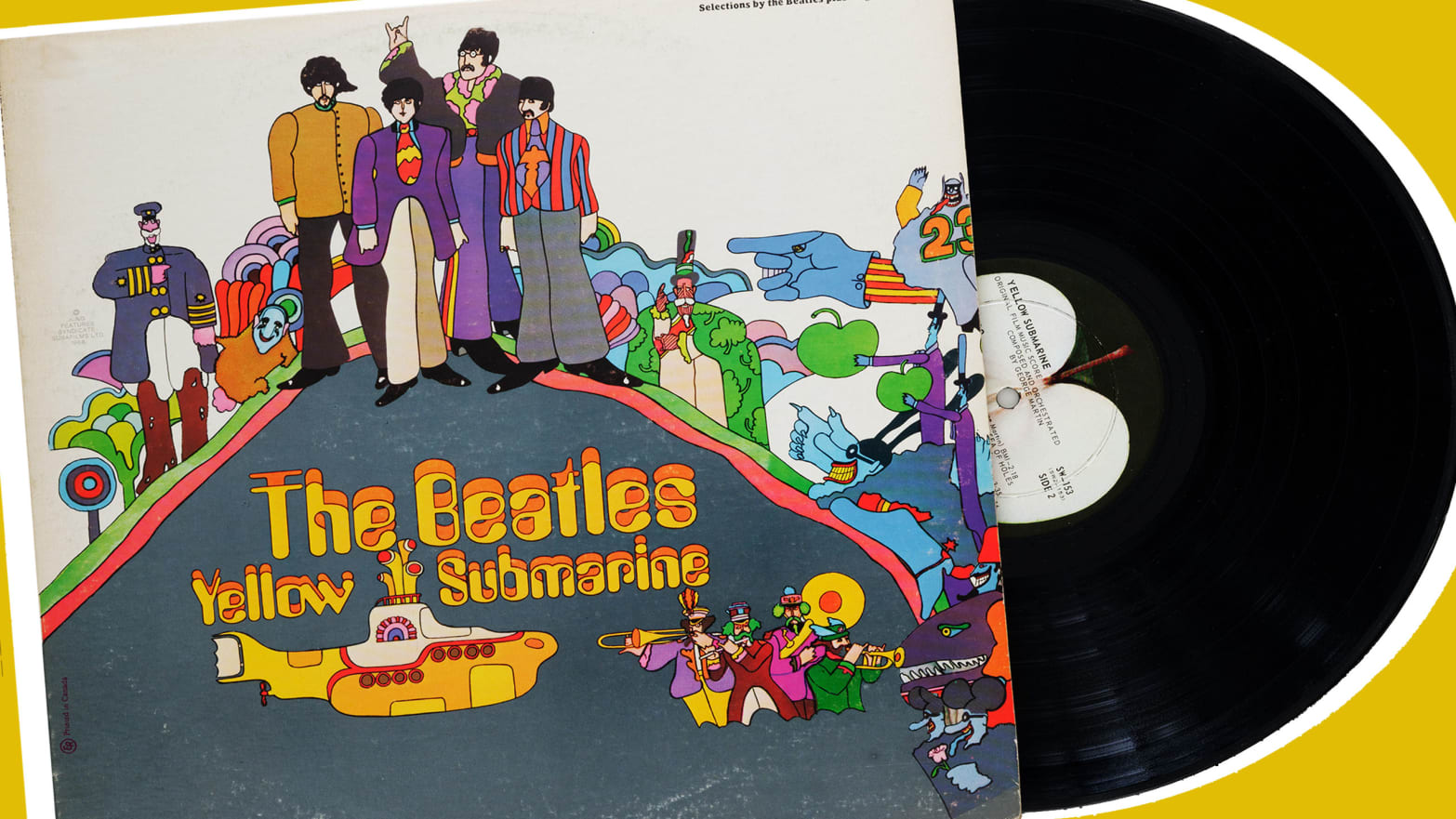

A collective that presents as a rugged individualist is a formidable one, and in the case of the Beatles, it’s what allowed them to both serve up the tunefulness to make a melody master like Schubert say “my my,” and also scrabble about to mine their peculiarities. But just as “You Know My Name” is the great lost Beatles song in plain view, their Yellow Submarine album, which came out 50 years ago on January 13, is the lone unmentionable of the Beatles catalogue. People act like it didn’t happen, as though we took a straight shot from The White Album to Abbey Road, with Let It Be and the Get Back mess—or, rather, the anecdotes of it, and what was salvaged from it—being a kind of PS to their career.

Recently there were a lot of puff pieces on The White Album—a slew of listicles ranking its best songs. But though the Yellow Submarine material predates The White Album in the recording chronology, the latter freed up the Beatles’ inner weird to put out the disc in the first place. I would argue that there are no songs on The White Album, let alone best songs and bad songs. It is an exegesis of styles in song forms that are both idiomatic and representational. It’s meant to show you all the colors of the paint box, rather than the paintings on the wall. Which is pretty strange.

People steer clear of the Yellow Submarine album because of the lazy diagnosis that its first side—that is, where you find the songs by the Beatles—represents their ennui following the heights of Sgt. Pepper. This is Beatles-lite, psychedelic-style. Then on side two, we get a bunch of classical music movie soundtrack compositions from George Martin, channeling his inner Bernard Herrmann. Then there is the film itself, which is suffused with a downbeat mood that clings to the picture like, well, reality. The Beatles had next to nothing to do with the movie, but it was as if in that proprietary Beatles way, their profundity informed the spirit of the entire venture.

The worst thing a Beatle could say about a piece of music was that it was Muzak. We all know Muzak, even if we’re less familiar with the word itself these days. It’s that somehow-even-drossier version of Christopher Cross’s “Sailing” in instrumental form that you hear in the mall elevator. When I was a kid and first getting into the Beatles, I sometimes heard the American iterations of their albums before their proper English ones. That’s how I became acquainted with A Hard Day’s Night, which had something approaching Muzak on its second side.

But those instrumental versions still felt weird and detached from plain, ordinary cliché; I didn’t play them a lot, but they intrigued me, such that I wondered if they ever thought of doing this elsewhere. Of course, they did, I just didn’t know it yet. Martin’s orchestral numbers on Yellow Submarine always suggest to me a strobe light with its power failing and a shirt draped over it, this anglerfish flickering in the dark. I find it comforting. The Beatles, of course, never granted him the opportunity anywhere else to write like this. I hear a man enjoying himself.

The glissando that starts “Sea of Holes,” coupled with those phlegmatic piano clusters that sound like a pudgy person’s footsteps on some distant underwater moon, stir wonder. Which is what the film is all about. And I’m sorry, but the “Pepperland” theme is as memorable as any in 1960s cinema. Good old George hit upon a big-time melodic refrain there. It’s pure movie soundtrack heaven.

But people weren’t buying this then or listening to it now for George Martin’s writing. If you took the portion the Beatles did and made it an EP, you’d have one of your dozen-best EPs in rock-and-roll history.

Give me weird Beatles, please, which is why I deeply dig this album side. All of the talk of how they believed in George Harrison is, alas, a lie. John Lennon and Paul McCartney wanted no part of Harrison’s songs on their proper albums. I don’t know if Harrison knew that he had to write something like “Something” to get a prime album spot and that’s why there could be such a gap between his best and his regular work, like he was dispirited, but I do know that his junior status as he got better as a musician and writer is one of the reasons they were not going to stick with it together. It was that a lot more than, say, Yoko Ono.

There are six songs on Side A, but one, as the Beatles would joke, was an oldie in “Yellow Submarine,” from way back in 1966—which in Beatles time was about 70 years prior—and “All You Need Is Love,” which is also the most untrue chorus ever sung in music history, from 1967. Of the other four numbers, two are by Harrison, and together they constitute a jettisoning. “Only a Northern Song” is a Harrison bitch-fest about the lack of respect he was shown. It’s pretty didactic, but also pretty funny, because Harrison had a way of mixing up the two. He even mixed up the two during his solo scene in A Hard Day’s Night when he’s telling off the fashion honcho who is trying to tell him that he’s not cool enough to even understand what he likes.

There are a lot of overlaid sound affects on “Only a Northern Song,” like Harrison was cribbing from the 20th take of “Revolution,” in which he and Lennon attempted to blend the familiar White Album version of the song—with its loping, opening guitar riff—with the collage aspect of “Revolution #9.” The song plays on the fact that Harrison had sold away the rights to his own compositions earlier in the Beatles’ career, so, basically, here, suck on this oddity.

The Beatles did a lot of meta stuff around this time. “Glass Onion,” for example. They were referencing themselves quite a bit, talking directly to you, the listener, as if singer and hearer were conspiratorially in on a joke, which is the fulcrum of “Only a Northern Song.” Harrison was tetchy, you might say, but wow did that tetchiness get a glorious airing and purging on “It’s All Too Much,” the other Harrison song on the record.

By this time, Harrison was one of the best guitar players in the world. He wasn’t in 1965. His technical development as a guitarist is one of the most underappreciated parts of the Beatles’ career. Boy could flat out play, and he’s damn near Hendrixian here.

So it has always amused me that, with Harrison doing what he was doing, McCartney was serving up “All Together Now,” one of those songs that, in its later morphings—and he did a lot of them—would get him branded a fuddy-duddy.

This will take you back to singalongs in the nursery school sandbox, but that’s hardly a bad thing. Even when McCartney did what could have been dross, he remained one of our peerless melodists. He could out-melody you, and that’s really where he separates himself from every other rock composer. That is the home ballpark, you might say, in which McCartney was unbeatable.

This was bad for him, because he became too reliant on it, and his work said less and less of substance—ideologically, emotionally, sonically, and structurally. But I feel that if I was a young child and I heard this, it would instill in me a love of music. I’d want to bust out my crayons and color something to it as I listened. And as an adult it “takes me back,” to paraphrase McCartney on The White Album. The best music moves us. That can be backwards, forwards, both. It makes our mind ambulate.

But then we have what I maintain is the most overlooked song in the Beatles’ entire catalogue, one I’d number among their dozen or so finest: John Lennon’s “Hey Bulldog.”

This song has an edge you rarely get even in rock. Lennon at his best could bring this edge, but he often saved that edge—or could only deploy it—on covers like “Twist and Shout,” “Money,” and “Keep Your Hands Off My Baby.” With “Hey Bulldog” it is like he wrote an Arthur Alexander-type number for himself, so he could belt away with it. McCartney and Lennon used to egg each other on to see who could knock the shit out of a song better. They may have conspired to keep Harrison down, but they sure had no problem competing with each other. This is that kind of vocal performance, a “try and top that, boyo,” one.

Lennon starts by name-checking animals. There’s a sheepdog—shades of “Martha” from The White Album—and a bullfrog. McCartney makes amusing answering noises like Lennon did on their cover of the Coasters’ “Three Cool Cats.” The Beatles were often trailblazers; but as they blazed their trails, they were also always looking back. They are our most Dickensian band, because they existed in the past, present, and future. Harrison is playing one of the top Beatles riffs—bluesy, slightly distorted, suggestive of a Fuzz-Tone but not quite fuzzed.

“Childlike no one understands / Jackknife in your sweaty hands.” This is like the pocket-sized version of “Strawberry Fields,” but for rockers. Lennon’s vocal comes across as importuning, as if he’s owed something, but also insouciant, like you can go screw if you’re not going to cough up what you should be coughing up.

I’ve always liked how Lennon makes “If you’re lonely you can talk to me” sound like “If you’re lonely you can’t talk to me.” That duality. On the extemporized coda, Lennon opts to pretend he’s bantering with a dog, asking the dog if he can speak, which makes them all start barking like madmen and howling with laughter. You think it’s going to end that way, but then Lennon calls for quiet, just so he can lay back into the vocal groove of the chorus one more time. That is the stuff and I will take another hit, please. Give me weirdness or give me death—or, if not death, something else as pleasingly nutso as all of this.