The Mets beat the Cubs decisively in the NLCS earlier this week. Not only did they win every game, they never so much as trailed. And so what promised to be an exciting series was a dud—unless you root for the Mets, of course, then it was heavenly. But the match-up reminded us that these two teams have a history—when the Mets won their first championship in 1969 it was in part because the Cubs gagged away the division. Then, in 1973, the Cubs were there again, fighting with the Mets—not to mention the Pirates and Cardinals—until the last weekend of the season. If ’73 isn’t as memorable as ’69 in New York, it’s because the Mets lost in the World Series. But the drama of the regular season—which included plenty of sloppy, mediocre ball, labor unrest, and personal tragedy—was irresistible.

Adapted from a chapter I wrote for the fine Baseball Prospectus anthology, It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over—edited by the talented Steven Goldman and featuring essays from Kevin Baker, Allen Barra, and Nate Silver—dig into the strange, compelling 1973 National League East pennant race.

—Alex Belth

The booze, smoke, and good spirits were flowing at Willie Stargell’s home in Pittsburgh on New Year’s Eve 1972. Some of his Pirate teammates who lived in town were there with their wives. Stargell was a warm, emotionally direct man who spoke softly, loved to laugh, and had a gift for putting his teammates at ease. Soul music boomed from the stereo.

After midnight, a friend told Stargell about something troubling he had just heard on the radio. Stargell went upstairs to listen for himself, then he picked up the phone and called a friend who would know more. The friend was home. Stargell listened. When he hung the receiver up and walked back downstairs, people were leaving quietly.

Al Oliver had left the party earlier and was lying in bed when the phone rang. “Scoop,” said Stargell, “a plane went down in San Juan and they think Roberto was on board.”

Oliver could not fall back to sleep. Neither could any of the Pirates upon hearing the news that their teammate, Roberto Clemente, might have been aboard a plane that had crashed outside of San Juan, Puerto Rico. Pitchers Steve Blass and Dave Guisti had thrown their own raucous party across town that night. At 5 a.m., they drove to general manager Joe E. Brown’s house, looking for more information. Later that morning, they arrived at Stargell’s. Another teammate, Bob Moose, joined them. The four men sat, hung-over, and cried. Later, most of the team gathered at broadcaster Bob Prince’s annual New Year’s Day party. “Nobody knew what to say to each other,” recalled Oliver, so they acted like men and commiserated together in silence.

A major leaguer since 1955, Clemente was a perennial All-Star who had been, he felt, slighted by the press, but had finally received his due after a brilliant performance in the 1971 World Series. Shortly after watching the Pirates win in seven games against the Orioles, Roger Angell wrote that Clemente had played “a kind of baseball that none of us had ever seen before—throwing and running and hitting at something close to the level of absolute perfection, playing to win but also playing the game almost as if it were a form of punishment for everyone else of on the field.”

“One couldn’t face Roberto after having a bad game,” Stargell later wrote. Clemente was stoic and reserved around outsiders, particularly the press, but he was engaged and comfortable in a Pittsburgh clubhouse. Guisti would scream at him in Italian, and Clemente would shout back in Spanish. Blass recalls Clemente chewing him out in jest when he found the pitcher reading a porn magazine in the whirlpool before Game 7 of the ’71 Series. The pitcher was a cheerful, self-deprecating man; he and Clemente were not the best of friends but they genuinely liked each other. Blass was chosen to deliver a eulogy on behalf of the Pirates at Clemente’s funeral in Puerto Rico on January 3, a variation of the same speech that was read at Lou Gehrig’s funeral decades earlier. Like the Iron Horse, Clemente would be quickly ushered into the Hall of Fame.

***

Joe Torre smoked a long, black cigar in the visitor’s locker room in Philadelphia and watched former White House council John Dean speak in front of a Senate Hearing committee on a television set several feet away. Dean was a mild-mannered man in brown tortoise shell glasses. He looked like an accountant. Torre was a grave-looking, heavy-set man, a butcher or undertaker or Luca Brasi. It was late June 1973, and it was hot. Reserve catcher Tim McCarver remembers Torre being the most interested in the Watergate hearings of all his teammates. Most of the guys in the league didn’t pay much attention, but Torre was intrigued.

John Dean’s voice was hoarse as he sat in front of the committee for the second straight day and explained in detail how his former boss, Richard M. Nixon, was in on the cover-up of the Watergate break-in and how the president also kept an extensive list of his enemies.

The Watergate hearings were a little more than one month old, and Dean was aware that he was in a David vs. Goliath situation. A good many Americans may have suspected that the president was capable of breaking the law—he wasn’t called Tricky Dick for nothing—but Nixon had not been found guilty of any wrongdoing yet. In accusing the president of the United States of being a crook, Dean was a man alone. But he spoke “with deadly earnestness,” according to The New York Times. “He wants to be believed.”

A respected veteran hitter who had been League MVP in 1971, Torre was committed to playing by the rules, either of baseball or government. But like Dean, he was not afraid to speak his mind, even at the risk of alienating his employers. Torre’s affiliation with the Players Association had already caused him to be traded once, from Atlanta to St. Louis in 1969; he was ripped by the fans on the road and at home for his role in the strike of 1972. “I understood why they were booing, but I was hurt,” he remembered years later. “I was too sensitive about it.”

Along with Tom Seaver and Jim Perry, Torre was the most visible player representative in the game. He had become a presence at the bargaining table alongside Marvin Miller, the executive director of the Player’s Association, and Miller’s head council, Dick Moss. Torre had worked on Wall Street and in the finance industry during the off-season for years. He understood power brokers and how to handle himself in their midst. John Gaherin, the owner’s council, told historian Chuck Korr that Torre was “the original godfather, talking out of a cloud of cigar smoke.” He recalled Torre as a level-headed optimist in a room dominated by pessimism and volatility.

The Phillies and the Cardinals were playing two that day, and Torre spoke to a writer from The New York Times about the ups and downs of the St. Louis season. The Cards started the year by losing 20 of their first 25 games, and then played better than .600 ball for three months. Torre explained that one of the critical reasons for the team’s success was improved relations with management, particularly with the Cardinals owner, Gussie Busch.

Busch was a Nixon man, and as such was unable to understand the players’ need for a union anymore than he or the president could comprehend the protests and picketing by young Americans across the country. More than any other sport, baseball represented the Old Guard. Only a few years earlier, Dodger owner Walter O’Malley said, “These are times when people spit on the flag, when priests go over the fence. You have to understand the pattern of things today. There is rebellion against the establishment, and baseball is linked to the establishment.”

Busch had been good to his boys; he treated his players better than any owner in the National League. What did he get in return? Ingrates who wanted more rights and more money. In 1972, Busch finally lost his composure. “Let ‘em strike,” he barked to reporters in a hotel lobby shortly before the players did just that. The first major strike in American sports history lasted ten days, exposing the collective weaknesses of the owners, while fanning the resentment of fans and sportswriters alike. It was tough for the players to feel that they had won anything when they went back out to play in front of thousands of increasingly disillusioned and spiteful fans.

Busch let his anger get in the way: He traded two pitchers holding out for more money (Jerry Reuss and Steve Carlton). Ted Simmons, a promising 22-year old catcher, could not agree to terms with the team either and played without a new contract. Under the reserve clause, his previous contract was simply renewed. But if Simmons went the entire season without coming to a new agreement, he would be able to challenge the legality of the reserve clause. His teammates admired Simmons’s resolve, especially during the long, cruel baseball summer. In the end, Busch blinked first and coughed-up a new two-year deal by early August.

The owners did score a victory when former Cardinal Curt Flood lost his antitrust suit against MLB in the Supreme Court in June 1972. Flood was old news for Busch but a constant reminder of everything that he could not countenance about the direction America was headed. By the time his case reached the high courts, Flood had fled the country, an emotionally distraught man. In Our Gang, Phillip Roth’s 1971 comic novel about Nixon, Flood appears as a prominent member of the president’s list of enemies.

“Flood, and his mouthpiece [former Supreme Court Justice, Arthur] Goldberg, appeared to be out to destroy the game beloved by millions,” says one of the president’s advisors in the novel. Marvin Miller later noted, “Roth was joking, but the point survives the exaggeration: What Flood was trying to do was perceived as a revolution.”

The St. Louis clubhouse had been known for its harmony in the ’60s but had become an antiseptic, cold place. The chill was lessened before the ’73 season started, however. Busch may have despised Marvin Miller and the union, but he still had paternalistic feeling for his boys. He couldn’t keep a grudge forever and no player saw his salary cut.

The Cards and Phils split the double-header that day, and St. Louis’s record stood at 34-36. They were eight games out of first place and had every reason to believe that they could win the division. So, in fact, did virtually every team in the National League East. Earlier that spring, Yogi Berra, the Mets manager, predicted that it would take just 85 victories to win it.

In a season in which the American League introduced the designated hitter and Hank Aaron closed in on Babe Ruth’s venerated home run mark, it seemed as if nobody wanted to win the NL East. Each team except the Phillies—who had improved but slightly from their miserable 59-97 showing in 1972—had reason to believe that they could win. The Pirates had the best hitting and had won the East the previous three seasons (they would win it a total of seven times in the decade); the Cubs had veteran sluggers like Billy Williams and Ron Santo, as well as an ace pitcher in Fergie Jenkins; the Mets had superior starting pitching, led by Tom Seaver, and even the Expos put together their best season to date, propelled by breakout seasons from outfielder Ken Singleton, fireman Mike Marshall, and rookie starter Steve Rogers.

The winner of the East would own the dubious distinction of long having the worst record of any playoff team in baseball history. But mediocrity in no way lessened the tension and excitement of what turned out to be an unpredictable, free-for-all battle in September, which saw no fewer than five of the six teams in contention for the flag in the final days of the season. Tug McGraw, the charismatic relief pitcher for the Mets, coined the phrase, “You Gotta Believe” that summer, and, as it goes with McGraw, there was a funny story behind that one.

In a year when cynicism ran deep, in and out of the game, “You Gotta Believe” was a rally cry that every team in the East could have applied to its season. It was a slogan made for Madison Avenue, but made innocently enough, intended to be taken at face value, without irony. Americans’ belief in their government was shaken, and baseball fans’ belief in the players, the owners, even their own perception of the sport as a symbol of less complicated times, profoundly disturbed. Still, You Gotta Believe. In what, exactly? Perhaps just the fantasy that professional sports were still a game.

But the most enduring line from that summer belonged to Yogi Berra, or was at least attributed to him. If the 1973 NL East demonstrated any one thing about baseball, it would have to be that “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.”

***

During spring training, Clemente’s absence was just beginning to hit many of his teammates; still, the Pirates were a formidable offensive team with decent pitching. For his part, Blass had an uncommonly good spring. Blass was a control pitcher just coming into his own. He was the surprise hero of the ’71 Series but refused to let sudden success go to his head. “You can’t get carried away by what happened in one week,” he said in 1972. “You can’t allow it to make you think you’re something that you’re not.”

Blass won 19 games in ’72, going 8-1 with an ERA well under 2.00 during the last two months of the season. But in his first 11 starts of ‘73, Blass was 3-3 with a 8.21 ERA. He wasn’t overly concerned, as he remembered struggling terribly at the start of the 1970 season. But May turned to June, and something appeared to be seriously wrong. Blass’s splendid control deserted him, and soon, he was in something more than a slump. He had never experienced control problems in his life, now he simply could not get his body to do what it had always done effortlessly.

Blass hit rock bottom against the Braves in June. On Friday night, June 11, he was knocked out of the game in the third inning, having allowed five runs on eight hits. Two days later, he was brought into the game in the fourth inning with the Pirates down 8-3. Blass pitched one-and-a-third innings, and surrendered seven runs on five hits, six walks, and three wild pitches. The Pirates ended the day 24-30, nine games out of first place.

“You have no idea how frustrating it is,” Blass later told Sports Illustrated. “You don’t know where you’re going to throw the ball. You’re afraid you might hurt someone. You know you’re embarrassing yourself but you can’t do anything about it. You’re helpless. Totally afraid and helpless.”

Blass received every kind of advice possible. Everybody had a theory as to what was wrong, and everyone offered a cure. Blass saw a shrink, tried meditation and was grateful for the support he received, but nothing helped. He believed that he’d snap out of it eventually. There was nothing physically wrong with him, and while Blass retained his sense of humor, he became almost unnaturally calm, making a deliberate effort to take it all in stride. Perhaps he was taking it too well. Guisti remembers Blass’s wife asking him to shake her husband up, but Guisti was careful not to probe too deeply and risk losing a friend in the process.

The following season in a profile for Sports Illustrated, Pat Jordan wrote that Blass was a lot like the stock Woody Allen character. “Like Allen he is forever mocking his success and himself, as if secretly he distrusts it all,” wrote Jordan. “Blass gives the impression that he feels he is losing things he has possessed fraudulently. Sooner or later he had always expected to be exposed.”

***

Blass was not the only pitcher searching for clues early in the summer. Tug McGraw, the Mets demonstrative and wildly entertaining closer, was also experiencing the worst slump of his career. Over the previous two seasons, McGraw put up a 1.70 ERA in 217 innings. He was handsomely rewarded when the Mets made him the highest-paid relief pitcher in National League history with a $75,000 contract. McGraw had a broad, cartoonish jaw, and a mischievous smile. During batting practice when pitchers shag fly balls, McGraw would lie out and make reckless dives. When he walked off the field after a big out, McGraw would slap his glove hand on his thigh, hollering. Is it any surprise that his best pitch was the screwball? “He had four or five different words for titties,” remembered Mets outfielder Ron Swoboda, “very much a California mentality.”

Yet for all of his exuberance, McGraw was troubled. After the Kent State shootings in May 1970—when National Guardsmen killed four students and wounded nine others during a demonstration—McGraw fell into a depression, temporarily unable to perform. That summer, he wrote in his diary:

“I want to know the difference between right and wrong: I don’t. Sometimes you think you do because you have been brought up a certain way, the way of your parents or school, church or country. But every morning you wake up only to discover that your parents are divorced, your school is not with it, and your church is struggling, and, worst of all, your country is falling apart.”

McGraw, who served a brief stint in the Marines during the mid-’60s, was as disillusioned with the government as he was with the student protest movement. “It must be the people that are screwed up,” he wrote. “I don’t know in which direction to head or what to do. Why? Because I’m a people and I’m screwed up. I think the reason I love baseball so much is because when I come into a game in the bottom of the ninth, bases loaded, no one out and a one-run lead … it takes people off my mind.”

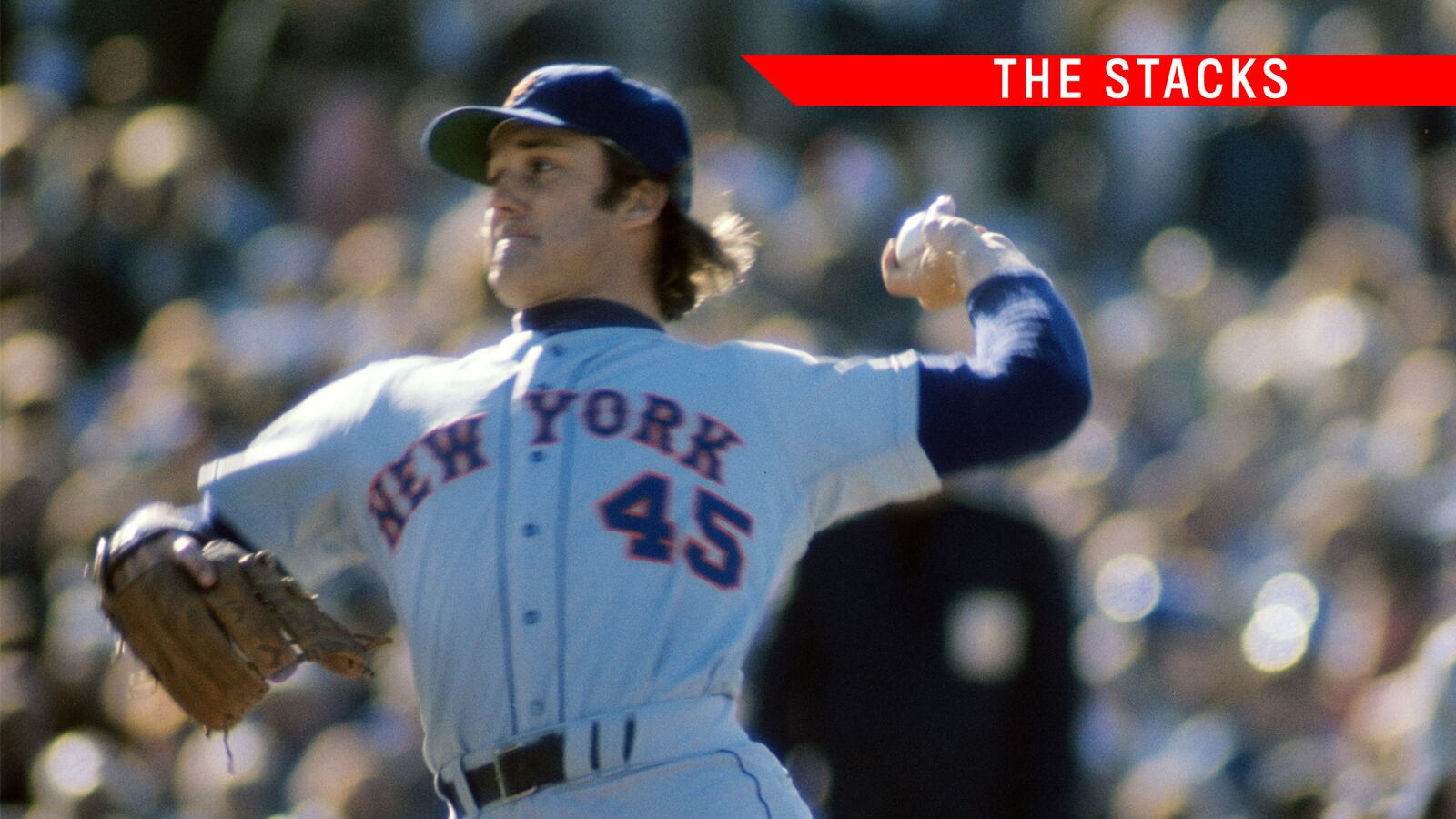

The Mets had fielded decent teams in the three years since they won the World Series in 1969, but they were not a force. Pitching was their strength. Tom Seaver was arguably the best starter in the game, Jerry Koosman was a talented number two (though he was coming off a rough season), and John Matlack was a formidable number three. But the Mets didn’t have enough hitting. They also had an unfortunate habit of trading away valuable young players. Nolan Ryan was the most famous Met to be shipped off, but Amos Otis, Ken Singleton, Tim Foli, and Mike Jorgenson were all traded away as well.

When manager Gil Hodges died in the spring of 1972, the Mets brought Yogi Berra in to replace him. Berra hadn’t managed since the Yankees let him go for winning the pennant but not the World Series in 1964. Berra was liked by his players but the running joke on the Mets was that the difference between Yogi and Hodges was three innings. In the third inning, Hodges was thinking about what he wanted to do in the sixth inning, and in the sixth inning, Yogi was thinking about what he should have done in the third. The Mets also acquired Willie Mays, another New York icon of the ’50s, who was at the end of his career. In a baseball sense, Mays had returned home to die. He was well-liked by his teammates but utterly mortal on the field, a sight that pained many longtime fans.

Injuries killed the Mets during the first part of the 1973 season—catcher Jerry Grote and shortstop Bud Harrelson the two most crucial losses. McGraw started the season well enough, allowing two runs over 11 innings in April. Then on a Friday night in early May at Shea, the Mets were leading the Houston Astros 5-2 in the eighth inning. The bases were loaded and there was one man out when McGraw replaced Koosman and walked the first batter he faced to force in a run. He struck out Lee May next, then walked the next two batters to tie the game. Berra yanked him. McGraw could not get over it—both his inability to throw strikes and the fact that he was pulled from the game.

McGraw’s ERA was 5.95 in May, and 6.00 in June. On July 3 the southpaw gave up three walks, a single, double and a homer, seven runs in all.

“I didn’t have any idea how to throw the baseball,” McGraw wrote in his book, Screwball (published the following spring). “It was as though I’d never played before in my entire life. I just felt like dropping to my knees and saying: Shit, I don’t know what to do.”

When the team returned from Montreal, McGraw went to see his friend Joe Badamo, an insurance salesman who had been close with Hodges. Badamo was something of a motivational coach and McGraw had been meeting him regularly for years. In the course of their conversation, Badamo told McGraw that he had to believe in himself, to visualize success. On his way into Shea Stadium that night, a group of fans were waiting for the players. They asked McGraw what was wrong with the team. “There’s nothing wrong with the Mets. You gotta believe!”

Shortly thereafter, with the team squarely in last place despite another brilliant season from Seaver, M. Donald Grant, the owner’s right-hand man, gave the team an old fashioned pep talk. Grant fancied himself a baseball expert and was sincere with the players even if he came across as a stuffed shirt. Over the course of his speech, he stressed that the team had to believe in themselves. When he was finished, McGraw popped off his stool, flexed like a pro wrestler and yelled, “You Gotta Believe! You Gotta Believe!”

That cracked everyone up, but McGraw’s performance did not improve. Finally, by the middle of July, he was “demoted” to the starting rotation. On July 17, McGraw allowed seven runs, on ten hits over six innings. The Mets scored seven in the ninth and won the game. He didn’t pitch again until July 30, and he fared better this time, only giving up a single run in 5 and two-thirds innings in a 5-2 loss.

***

While McGraw struggled to regain his groove, the best screwball in the league was being thrown by a right-hander, fellow relief pitcher Mike Marshall, a converted infielder with a stocky body and a sharp mind (an academic fascinated by the science of pitching, Marshall was working towards a Ph.D.). He was 27 when he arrived in Montreal during the 1970 season, and it wasn’t long before he hit it off with Gene Mauch, the team’s tough, controlling manager.

“He was very receptive to collaboration,” Marshall recalls. “I’ve never seen a manager more in touch with his players. He was great with the players who knew what the hell they were doing. He could also be cantankerous with the idiots on the team.”

Mauch admired Bob Bailey, the team’s veteran slugger, and absolutely loved Tim Foli, his short-fused shortstop. Foli’s nickname when he played for the Mets was “Crazy Horse,” and with good reason. He made a name for himself fighting with coaches, teammates, opposing players, and umpires. Easy Eddie Kranepool once punched him in the mouth. After going 0-5 with several errors in a minor league game, Foli took his glove and record player to the field and slept next to second base that night, swearing to himself that he’d never have such a bad game again. “He had a bad night and he went home to sleep,” said Mauch later. “His home is shortstop, that’s all.”

Mauch did not have a playoff-caliber team in 1973. Montreal’s fielding was awful and they didn’t have enough starting pitching. But the emergence of Ken Singleton (.302.425/.479), along with a thrilling second-half rookie debut by a high-strung right-hander Steve Rogers (10-5, 1.54 ERA in 134 innings), gave the enthusiastic fans of Montreal something to get excited about. Marshall was a key reason for their improvement. He had been lobbying Mauch, his frequent bridge partner, to use him more often ever since he arrived in Montreal. “He was a stubborn SOB,” says Marshall, who threw 111 innings in 1971, and 116 the following year; in 1973, he tossed 179 innings—all in relief—to the tune of a 2.66 ERA.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, the Cubs spent the majority of the summer in first place. But Chicago was an old team. Ron Santo was having a disappointing season, and though his final numbers were more than decent (.267/.348/.440), it would be his last as a Cub. Fergie Jenkins had a losing record (14-16) after winning 20 games for six straight years, and he too would be traded during the winter. Still, the Cubs overachieved, thanks in large part to strong, first-half performances from Rick Monday (.267/.372/.469) and Jose Cardenal (.303/.375/.437). But it all came to an end in the thick of the summer; Chicago was 52-46 in the first half of the year, 25-38 in the second.

The Cardinals snatched first place on July 22, led by Lou Brock (.297/.364/.398) and Ted Simmons (.310/.370/.438), and stayed there until the last day of August. But they lost their ace, 37-year-old Bob Gibson, to a knee injury on August 4. The team’s record was 12-18 for the month, yet they managed to remain in first. When the Cardinals beat the Mets, 1-0 in 10 innings on August 30, Tom Seaver’s record fell to 15-8 (though his ERA was 1.71). Seaver went the distance in the loss. With 23 games left in the season, the standings looked like this:

WLGB St. Louis6865-Pittsburgh63652.5Chicago64673Montreal62705.5Phillies62716New York61716.5

***

The Pirates tied the Cardinals for first place on September 1, but then lost four of the next five games, which resulted in the firing of manager Bill Virdon. Old reliable, Danny Murtaugh, in his fourth stint as Pirates skipper, took over. But the Pirates had struggled all season long with their roster. Catcher Manny Sanguillen replaced Clemente, his best friend, in right field. The experiment lasted through the middle of June, at which point Sanguillen returned to catching. The Pirates couldn’t decide if Sanguillen or Milt May should be the full-time catcher, whether Bob Robertson or Al Oliver should be the everyday first baseman. They also struggled to solidify their middle infield positions. It was as if everything went awry in Pittsburgh.

Willie Stargell had reluctantly accepted the role of team captain earlier in the season, and was having a sensational year (.299/.392/.646), with 43 doubles, 44 homers and a 119 RBI, but the team was underachieving. “I think we needed Roberto to push us,” Stargell wrote in his autobiography. “Without him, there wasn’t anyone around to crack the whip. Subconsciously, we waited.”

On September 11 in Chicago, Murtaugh gave Steve Blass a start, the pitcher’s first in six weeks. Blass had spent most of the summer pitching batting practice. The Pirates had called up a kid named Miguel Dilone just to stand at the plate as Blass pitched. “I pounded him,” says Blass today. “It got so that he’d hide in the hotel lobby when I was ready to pitch BP. He knew he was going to get it again.” Blass walked around Chicago until 5:30 in the morning before the start, obsessing about his mechanics. He didn’t perform too badly either, allowing just two runs on two hits and five walks in five innings. The Pirates lost, but Blass was encouraged. When he was taken out of the game he called his wife from the clubhouse and said, “I’m back!” The Pirates leap-frogged St. Louis into first place the next day and remained there when they began a five-game, home-and-away series against the Mets beginning on September 17. They were 7-3 under Murtaugh.

For their part, the Mets were winning, going 12-5 since the 1-0 loss against the Cards at the end of August. They were finally healthy and Tug McGraw was on a roll. While Seaver tired, Koosman and Matlack pitched well. But it was an unlikely lefty, George Stone (4-0, 2.15 ERA in September), who made a big contribution, just as normally light hitter Wayne Garrett was the team’s hottest hitter (.315/.407/.598 in September). New York began the two-game set in Pittsburgh just two-and-a-half behind the Pirates. But Seaver was bombed 10-3, and the defending champs looked primed to pull away from the rest of the division. The following night, the Mets trailed 4-1 going into the ninth inning but then scored five runs and went on to win, 6-5.

Stone and McGraw combined to give the Mets a 7-3 victory the next night as the series shifted to New York, where Willie Mays announced that he would retire at the end of season. “It’s been a wonderful 22 years,” he told reporters. “I’m not just getting out of baseball because I’m hurt. I just feel that the people of America shouldn’t have to see a guy play who can’t produce.”

On September 20, the Pirates held leads of 1-0, 2-1, and 3-2 before the Mets tied the game in the bottom of the ninth on Duffy Dyer’s single to left field. The score remained even when Richie Zisk singled off Ray Sadecki with one out in the top of the thirteenth inning. Manny Sanguillen flew out to right for the second out, and then Dave Augustine, a recent call-up from the minors, lined a shot to left over the head of Cleon Jones. The crowd at Shea gasped as the ball headed for the fence. But it did not clear the left field wall; it hit precisely on the top of the wall. It did not skip over for a home run, and it did not ricochet wildly back onto the field of play. Instead, it bounced into Jones’s glove. The left fielder spun and fired a strike to the cutoff man, Garrett, who then pegged the slow-footed Richie Zisk out at the plate by several feet.

Catcher Ron Hodges singled home the winning run in the bottom of the inning and the Mets were suddenly just a half-game behind the Pirates. Sensing the drama of the moment, more than 51,000 New Yorkers piled into Shea the next night to see Seaver, working on four days rest, start the most important game of the season. Blass started for the Pirates and didn’t make it out of the first inning (he later called his return start in Chicago, “a head fake”). It was the second-to-last start of his big league career. Seaver went the distance in a 10-2 laugher. Garrett and Grote each had three hits, Jones and Rusty Staub both homered. The Mets reached the .500 mark for the first time since May, and they were in first place. The Pirates were a half-game back, the Cards a game back, the Expos 1.5 games behind, and the Cubs only 2.5 games out of first.

A week later, little had changed. The Mets were still hot. Going into the final weekend series of the season, they led the Pirates by a game, with the Cards 2.5 back, the Expos 3.5 behind, and the Cubs still technically alive at four back. In the NL West, the Big Red Machine in Cincinnati had finally overwhelmed a talented young Dodgers club and were the favorites to represent the National League in the World Series no matter what transpired in the East.

The Pirates and Expos played each other, while the Cards played the Phillies and the Mets and Cubs squared off. The Expos beat Pittsburgh on Friday and Saturday, putting an ugly end to a painful season for the Pirates; Pittsburgh came back and clobbered Montreal on Sunday. With Gibson returning and going six innings in a 5-1 win, the Cards swept the Phillies, winning their last five games in a row and finishing with an 81-81 record. The Mets and Cubs sat around and waited in the rain. “The field is absolutely bad, almost a quagmire,” said the chief umpire, “And the forecast is bad for tomorrow.” When Friday’s game was called, a double header was scheduled for Saturday. When Saturday’s games were called, double headers were set for Sunday and Monday.

“It’s nice to be at home when there are delays like this,” said Ron Santo. “You can just go home and relax a lot more. The Mets have to sit around the hotel and try to kill time.”

With four games scheduled for two days, the Mets’ lead over the Cardinals was 1.5 games on Sunday morning, just two over the Pirates. The Cubs beat the Mets 1-0 in the opener as Rick Reuschel out-dueled John Matlack, but Koosman shut the Cubs down in the second game as the Mets pounded Jenkins, 9-2 to clinch at least a tie of the division.

St. Louis was only a half-game out. Joe Torre and Tim McCarver watched the Mets game at a convention hall in Atlantic City where they were being paid $500 to glad-hand businessmen at a paper convention. The teammates saw the game on TV and prayed for the Mets to lose. They wanted nothing more than to be in New York in the following day, facing the Mets in a one-game playoff.

Seaver took the hill late Monday morning in front of fewer than 2,000 fans at Wrigley Field. It was overcast and the field was a soggy mess. Seaver was exhausted, and allowed 11 hits and four runs over six innings, while striking out only two. But in the second inning, Cleon Jones hit his seventh home run in 11 days, and Grote singled home two more runs in the fourth. New York Mayor John Lindsey was addressing 500 recruits at the Police Academy on 20th Street that morning in Manhattan. When he gave a score update: Mets 5, Cubs 2, the auditorium erupted. Rusty Staub went 4-for-5, and Tug McGraw pitched three scoreless innings as the Mets hung on, 6-4. Believe it or not, the Mets had won the division.

A pot of chicken soup simmered in the visitor’s locker room at Wrigley Field as the Mets congratulated each other. “That’s the hottest champagne I’ve ever drunk,” said one New Yorker. The Mets celebration was muted as there was still one game left to play. Five minutes later, the second game was called and the place went bananas. “One, two, three, you gotta bee-lieve,” said Tug McGraw. “Unbelievable,” said Wayne Garrett, “You couldn’t have convinced me two months ago we’d win.”

From August 22 on, McGraw went 5-0 with 12 saves in 40 innings, allowing 12 walks while striking out 38. He did not surrender a lead once. “We couldn’t believe we had won it and that nobody wanted to win it. It got dumped in our lap,” Koosman remembered.

“I hit .239 and we finished the season in Chicago,” said Ed Kranepool after the game. “In 1969 I hit .239 and we finished in Chicago, too. Next year I’m going to hit .239 again. In between I’ve hit .270 and .260 and we haven’t won. I can make us all more money hitting .239.”

It was still several years before Atlantic City got a gambling license. Instead of going to New York for a playoff game, Torre and McCarver were stuck by the seaside in a dead-end town. “A bad trade-off,” says McCarver. Surely the Cardinals would have won the division had Gibson not been hurt. Then again, if Clemente were alive and Blass didn’t go from 19 wins to just three, the Pirates would still be champs. If Chicago hadn’t traded Ken Holtzman, who went 21-13, with a 2.97 ERA in 297 innings for the Oakland A’s, maybe they would have won it. And if a frog had wings it wouldn’t bump its ass a-hoppin’.

McGraw and his teammates latched onto a catchy phrase with “You Gotta Believe,” and it is tempting to imagine it was their collective faith that won the division. More likely, the Mets simply got hot at the right time, while the Pirates could not overcome a season of missed opportunities. After all, no player displayed more hope and faith than Steve Blass. Did believing help him?

For Gibson, the sting was lessened only by the Mets’ success in the playoffs—at least the Cards weren’t the only ones losing to New York. The Mets beat the big, bad Red Machine in a tense, five game series, and eventually came within a game of a championship against the A’s. The playoffs and World Series were filled with memorable moments—the Pete Rose-Buddy Harrelson fight, Pedro Borbon taking a bite out of a Mets hat, Willie Mays on his knees protesting to the home plate ump—but it was New York’s valiant playoff run which helped make the 1973 team, as well as the division race, memorable. What’s endured more than even the race, however, are those two quotes: “It ain’t over til’ it’s over,” and “You gotta believe.”

A few nights ago, the Mets celebrated their sweep of the Cubs in the NLCS. The party began on the field at Wrigley in Chicago. Behind the visitor’s dugout a gang of New Yorkers celebrated along with them. Of course, a few of them held up signs that read, “You Gotta Believe!”