The soldiers are blinded, their eyes covered in gauze, but they lead one another in line, hand stretched over shoulder, past the dead lying at their feet.

Off in the distance, off-duty soldiers play soccer. The mustard yellow background, tinged with a touch of pink, is nearly blinding and, at twenty feet across, the painting all but smacks visitors across the eyes with all the subtlety of a flamethrower.

“Gassed” by John Singer Sargent, on loan from the Imperial War Museum in London and on view in New York for the first time, is the centerpiece of World War I Beyond The Trenches, a new exhibition up at the New York Historical Society through September 3.

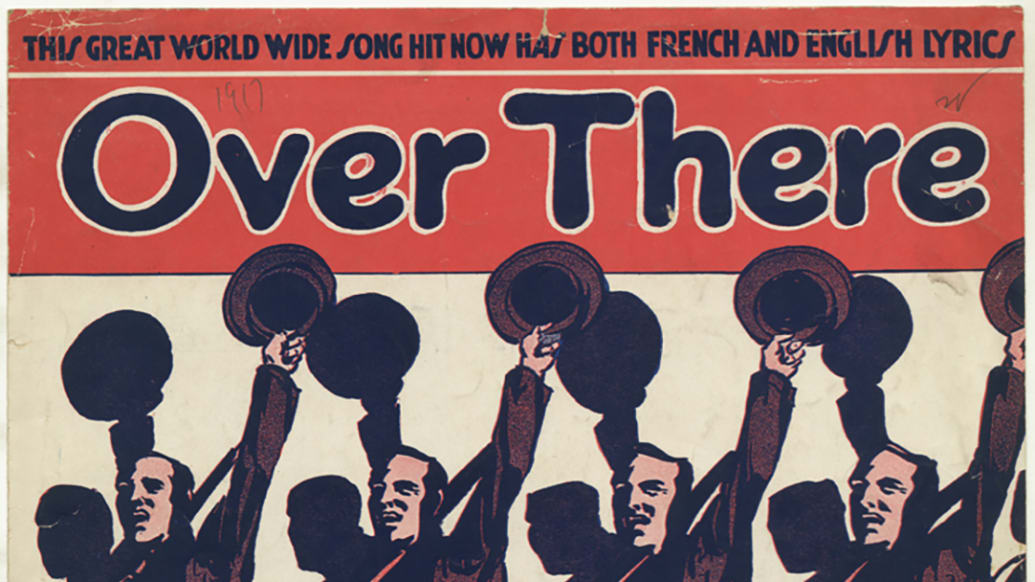

The occasion of the show is the 100th anniversary of America’s entry into what was then known as the War to End All Wars. The show is a tour around the battlefield, as it were, of the artistic and cultural milieu that sprung up around and in response to a war unlike any the world has seen.

Courtesy of Debra Force Fine Art, New York

As the show makes clear, the war helped make modern America. America began to see itself in the years leading up and immediately after the war as the world’s indispensable nation.

The Preparedness Movement, which called for military readiness even as President Woodrow Wilson and congressional leaders maintained a position of strict neutrality, believed that the war would make the world safe for democracy, and pushed a kind of American patriotism that the country had not yet seen.

Artists were enthusiastic foot soldiers in the propaganda effort. A series of Impressionistic paintings by Childe Hassam reveal city streets choked with patriotic paraphernalia. “The Greatest Display of the American Flag Ever In New York, Climax of the Preparedness Parade in May,” one is subtly subtitled.

George Bellows, who before the start of the war was a second generation Ashcan School painter most known for romantic and vivid depictions of urban life in New York City, went from war skeptic to war enthusiast with the publication of the Bryce Report, a lurid accounting of wartime German atrocities in Belgium.

Bellows made the claims found in the report—later found to be largely exaggerated--appear real. "The Germans Arrive," from 1918, depicts a couple of German soldiers holding down and chopping the hands off of a teenager leaving him helpless. Another soldier sets up a farm girl--presumably the now crippled man’s girlfriend or sister--while the rest of the town burns in the distance.

"Return of The Useless" shows starving and elderly Belgians, too worn out to work in forced labor, being dragged from a cattle car. The image echoes with images that were to overtake Europe a few decades later.

However, because the macabre depictions of Europe in the early days of the war by Bellows and others were largely discredited soon after the war’s conclusion, it led the world to believe that the situation in Europe in the 1930s wasn’t to be believed either.

New York Historical Society

Most of the country was against the war, but as the show makes clear, it would have been hard to not get caught up--not when propaganda posters featured a gorilla in a German military helmet and carrying in one hand a club that said “Kultur” and in the other a lithe American woman dressed in little more than sheet arriving on American shores. “DESTROY THIS MAD BRUTE: ENLIST,” the poster read.

Another, exhorting viewers to buy war bonds, showed Lower Manhattan in flames, the bright orange of the flames inching ever closer to the Statue of Liberty.

Once in, the war proved as catastrophic for the Americans as it had for Europe. More than 50,000 dead in just a few short years of fighting, and four times as many wounded.

Some of the strongest parts of World War I Beyond The Trenches show artists coming to grips with this grim account.

Claggett Wilson is largely forgotten today, but his watercolors explode with life and color in a style recognizably modern. Despite its tongue-tied titled, “Flower of Death--The Bursting of a Heavy Shell--Not As Looks, but as it Feels and Sounds and Smells” hardly feels like it can be experienced by the eyes alone, and is oddly beautiful despite the horror it depicts.

The same can be said for “The First Hepaticas” by Charles E. Burchfield, another painter not as well remembered as he should be. The famed James Montgomery Flagg “I WANT YOU” poster featuring the bony finger of Uncle Sam (which hangs in the exhibit as well) was a bit of a lark; all men of age were required to enlist to be eligible for the draft, but those that volunteered had a better chance at the placement of their choice.

Burchfield chose to take the risk and not volunteer, and “The First Hepaticas” is awash in a gray despair, an almost psychedelic deserted forest scene, a reflection of his interior mood as he awaited the conscription call. The very ground looks as if it will open up and swallow the painter whole.

A quieter kind of despair is evident in Georgia O’Keefe’s “The Flag,” which shows a blood-red American flag bleeding into the blue sky beyond.

Photography, Glenn Castellano. Courtesy of New York Historical Society

O’Keefe painted the work after visiting her brother who was stationed at a military training camp in West Texas. Such a simple image, but within it is plain all the torment over what happens when perceived patriotic duty divides loved ones from their home.

In the end, the war was too catastrophic, the leaders that plunged the world into it too blundering and misguided, for there to be any kind of hopeful note on this show.

But if there is it is too be found in “The Subway” a 1919 work by Walter Pach, yet another artist here whose work deserves much greater recognition. The war is over. New Yorkers are crowded into a subway car arriving at 8th Street in Greenwich Village, proof that the war had been a financial boon to America and helped spur a building binge.

An African-American soldier is on board, evidence of how the war helped spur ever so slightly the cause for greater civil rights back home. On the subway is an ad for cookies that can be bought at the store saving women hours that would otherwise be spent baking at home.

Somehow, the painting seems to say, the war ended, and the world moved on, heedless of its lessons.