Excerpted with permission from Pharaohs of the Sun: The Rise and Fall of Tutankhamun's Dynasty by Guy de la Bédoyère, published by Pegasus Books.

In the murky drama of Akhenaten’s aftermath and the first few years of Tutankhamun’s reign the small and scrappy Valley of the Kings tomb known as KV55 and its wrecked contents are never offstage. The controversies, bolstered by recent scientific evidence which has only muddied the waters further, have rumbled on ever since the tomb was found. However, the surviving evidence of the deposit suggests it was originally a reburial of Tiye and Akhenaten whose bodies were brought from Amarna by Tutankhamun for safety. Subsequent clearance work left behind only one male body of indeterminate identity, but undoubtedly a close relative of Tutankhamun’s, along with cluttered and damaged remnants of funerary equipment.

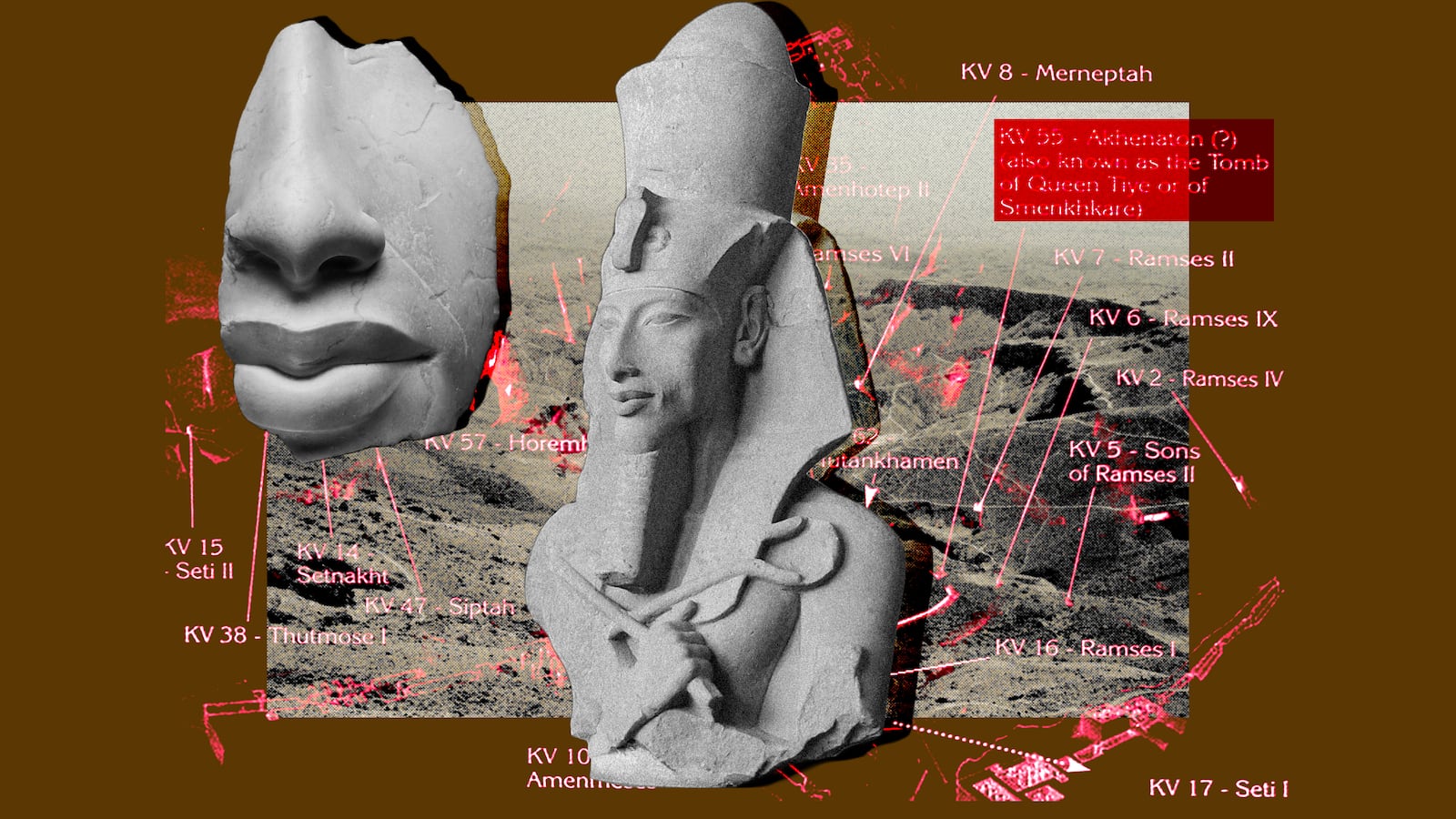

KV55 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings that contained a cache of material and bodies brought from Amarna after Akhenaten’s reign. It lies only about 120 ft (36 m) across the valley floor from Tutankhamun’s tomb (KV62). No other two 18th Dynasty royal tombs are so close to one another but neither had been designed originally as a royal tomb. They were far too small, corresponding to the tombs of nobles allowed the privilege of a burial in the Valley, such as Yuya and Thuya’s. Tutankhamun’s was subsequently modestly enlarged to squeeze in the paraphernalia of a king but KV55 was not. KV55 consists only of an entrance corridor, a rectangular burial chamber, and a small niche annex. There were no dockets or decoration that might have explained whose tomb it was. It had suffered from a chaotic burial of at least two bodies, after which it was reopened. Some of the contents were removed, leaving only one body behind in a royal coffin and some funerary equipment. Deliberate damage was caused to what was left behind, made worse by later water ingress and structural collapse.

The tomb had the misfortune to be found in 1907 by a team led by Edward Ayrton, then working for a wealthy American hobbyist Egyptologist called Theodore Davis who pressured them to make a hasty removal of the contents. The tomb was not recorded properly, or a plan made. Some small pieces were stolen and rapidly appeared on the local antiquities market. The result was to compromise permanently analysis of the assemblage though sterling efforts since have made good some of the lost information.

Nevertheless, the tomb yielded some important but controversial evidence. The most conspicuous relics were panels from a gilded wooden shrine intended for the burial of Tiye, commissioned for her by her son Akhenaten. The shrine had been in the process of being removed during the clearance work that took place within two centuries of the original deposit, but the job was abandoned when it became too difficult to drag the panels up through the corridor. The shrine parts were damaged, but they still bore scenes decorated with figures of Akhenaten and Tiye in the Amarna style. Akhenaten’s name had been cut out but the surviving inscriptions on the shrine described Tiye as Amenhotep III’s queen. The Aten’s name had not been touched.

There were four magic mudbricks. Three were in their niches in the burial chamber, and one apparently displaced in the little annexe. Akhenaten’s throne name Neferkheperure was still visible on two of the bricks, most clearly on the ‘northern’ brick. Such bricks were a common inclusion in New Kingdom tombs and carried protective spells connected to birth, and thus the rebirth of the deceased. The spells resemble, for example, those found in the tomb of Thutmose IV.

The shattered dereliction that greeted the discoverers of the tomb known as KV55. This view shows the badly damaged and defaced royal coffin which contained skeletal remains, usually identified as either those of Akhenaten or Smenkhkare.

Pegasus BooksThe tomb contained a royal coffin with a badly preserved mummy of an adult male reduced to a skeleton. The only names still visible on gold foil with the body were those of the Aten. Anything that might have identified the man had been carefully removed. There were also four canopic jars, each bearing portrait bust stoppers of a royal woman wearing the ‘Nubian wig’, popular towards the end of the 18th Dynasty. Each bust had been modified by adding the cobra uraeus symbol of royalty, subsequently removed. The inscriptions on the jars had been deliberately rubbed off, with only traces remaining. There were other items, but few were inscribed. Those that were mostly carried the names of Tiye and/or Amenhotep III. The sole exceptions were a collection of clay seals carrying Tutankhamun’s throne name Nebkheperure. There were no objects that carried Smenkhkare’s or Nefertiti’s names, or their shared throne name Ankhkheperure. Nor was there anything that could be linked to Meryetaten or other members of the Amarna royal family.

So much for what we know. What we can infer takes the story a little further. The battered shrine panels were of dimensions compatible with a restoration of Tiye’s sarcophagus from fragments found in the Royal Tomb at Amarna. It seems Tiye’s body had been removed along with the shrine and her other burial goods and taken to Thebes for reburial in KV55. Tutankhamun’s seals make it likely this was his decision; it certainly took place in his name.

The bust stoppers of the four canopic jars did not necessarily belong to the jars originally. While the wigs resemble the one that Kiya wore, the faces’ profiles resemble most closely Nefertiti’s (or by extension one of her daughters). The erased jar inscriptions left traces compatible with the names of the Aten, Akhenaten and a reference to Kiya’s unique title Greatly Beloved Wife. However, the traces really are just that. The only part of her title detectable on the jars now is the sign for wife, but barely, and is not definitive on its own. Kiya’s personal name is not visible and nor is her special title. Moreover, the restoration of her name and titles is founded on the assumption they were accurately laid out originally and did not replace an earlier text. As viable evidence this restored text is another non-starter. The erasure of the inscriptions was probably to prepare the jars for use in KV55 for the male burial. The best that might be said is that the jars were possibly Kiya’s but might have been fitted with stoppers bearing portraits of Nefertiti or another female member of the royal family. Although very similar in appearance, the stoppers are not identical. They may even have been manufactured as generic portraits of Nefertiti or her daughters, intended for any one of them who needed the equipment.

The coffin inscriptions were changed or defaced in two phases. The inscriptions on the coffin’s front and inside have the word Maat in the traditional form of the hieroglyph for the eponymous goddess. On the coffin’s foot the word is spelled out phonetically, an Atenist characteristic of the latter part of Akhenaten’s reign also found on Tiye’s shrine that avoided a direct reference to a divinity of the old order. The technicalities and restorations of the coffin’s modified texts are extremely complicated, but a plausible original owner was Kiya, after which the coffin was repurposed for a king in preparation for his reburial in KV55. This king’s names were themselves subsequently removed. Those on the lid of the coffin were neatly cut out from the cartouches in a way that suggests the plan might have been to replace them with someone else’s names, a procedure that was never completed. This work left in place key Atenist epithets used for Akhenaten, such as the ‘perfect little one of the living disk’, suggesting that the intended third(?) owner of the coffin was someone for whom these would be suitable.

(L-R) Tiye, KV55 canopic jar stopper, Tutankhamun and Nefertiti. The resemblance of the latter three to one another is obvious, raising the possibility that all three were related and that the Tutankhamun gold mask was not originally made for him. The resemblance of the stopper bust to Nefertiti is particularly strong in the nose and upper face, making it feasible that Nefertiti or one of her daughters was the subject.

Pegasus BooksThus, the coffin was most likely once a lesser wife’s before probably being reused for Akhenaten or Smenkhkare, or both. It is not possible to say which and nor would either necessarily determine whose body was found in the coffin. There was nothing unusual about reusing coffins and canopic jars. Possible contexts are that either Kiya’s burial equipment had never been used, or there was a general clearance of Amarna tombs during Tutankhamun’s reign which freed them up for redeployment.

Armed with this information it is possible to imagine some of what might have happened. On Tutankhamun’s instructions Tiye and Akhenaten were removed from the Royal Tomb at Amarna, together with selected portable funerary equipment drawn from their original burials. Other available pieces which might have included some of Kiya’s were added. These and the two bodies were taken to Thebes and reburied in KV55, possibly joined at some point by the ‘Younger Lady’. If so, Tutankhamun was therefore seeing to the burial of his parents, or at least those whom he believed to be his parents, and his grandmother. An effort was made to create a conventional 18th Dynasty royal burial, hence the magic bricks, and thus also reassert the dynasty’s entitlement to rule. The disappearance from the Amarna Royal Tomb of the remains of Meketaten and her younger sisters, and virtually all their burial equipment, makes it possible another reburial is still waiting to be found. It is also probable that some of the royal funerary goods taken from Amarna were set aside to be used in later burials, including eventually Tutankhamun’s.

Enough survives of the skeleton to be certain it is that of an adult male who was a member of the royal family. He was closely related to Tutankhamun, sharing what was at the time a relatively unusual blood group (A2/MN) and physical appearance which included the large pelvis, though this connection did not become apparent until after Tutankhamun’s body was unwrapped in 1923. No physical remains have been found in the Royal Tomb at Amarna, while the magic bricks made it possible, even likely, that Akhenaten’s body or a body believed to be his had been reburied in KV55 at some point. By default, Smenkhkare is the only alternative candidate to Akhenaten that we know of, apart from Akhenaten’s older brother Thutmose who had long predeceased Akhenaten’s accession to the throne. The only circumstantial physical inference we can draw from what little we know about Smenkhkare is that he was younger than Akhenaten and was a close family member. Nothing found in KV55 belonged to him, and even the material in Tutankhamun’s tomb that might have been his is not demonstrably so. Without the unidentified body and the deleted names on the coffin there would never have been any suggestion Smenkhkare had been buried in KV55, unlike Tiye and Akhenaten.

No named sculpture of Smenkhkare is known, so it is impossible to compare the skull with representations of him and Akhenaten. The identification debate has been based around the body’s estimated age at death, and most recently DNA which has been used to claim that the body, regardless of its identity, is that of Tutankhamun’s father, adding to the evidence of the shared blood type. This leaves unresolved the ‘highly contentious issue’ of Akhenaten’s family circle. One of the main reasons is that the only bodies whose identity is not in doubt are those of Yuya, Thuya, and Tutankhamun. Some believe that the KV55 body is that of a young man aged in his early to mid-twenties. Others prefer the idea that the age at death was thirty-five to forty, which is more consistent with what happened during Akhenaten’s reign but is not essential. That two such incompatible estimates continue to subsist inspires little confidence in the evidence.

Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their three eldest daughters Meryetaten, Meketaten and Ankhesenpaaten. Found at Amarna.

Pegasus BooksSticking with the lower range for age at death means those in favor of the body being Akhenaten’s arguing that his reign, religious revolution and large family, and all the known events, were packed into his adolescence and young adulthood. This is not impossible, especially given that becoming king as a child or an adolescent was common in the 18th Dynasty (or indeed in antiquity in general). In Akhenaten’s case, however, it is difficult to believe he was only in his mid-twenties by the time he had ruled for an absolute minimum of sixteen years in such an epoch-changing reign. Either way, nothing helps the case for Smenkhkare, who is the alternative solution for explaining the alleged youthfulness of the KV55 body, while sometimes also suggesting that he was Tutankhamun’s father but without any corroborating evidence. Had Smenkhkare been his father it would be necessary to assume also that Meryetaten was Tutankhamun’s mother. Since we know Tutankhamun died in his late teens after a reign of a little under a decade, he must therefore have been born around the 8th to 10th regnal year of Akhenaten at the latest, and when Meryetaten was still only eight or nine years old at most. This stretches the credibility of the case beyond breaking point.

Much more likely is that for different reasons the various estimated ages of the KV55 body at death and the DNA evidence are unreliable. DNA does not name or identify individuals. DNA markers can be used to identify potential relationships but cannot, for example, distinguish siblings. For example, one body’s DNA may be compatible with being the father of another but could also be an uncle. In a family with multiple consanguineous unions over several generations the potential for other options is even greater, involving cousin relationships that are now untraceable. The techniques used to estimate age at death are notoriously prone to major error for a variety of reasons, including the lack of any controls in ancient populations. These techniques do not name or identify individuals either. They have been demonstrated to be prone to significant error with a blind study conducted on the bodies of known age (specified on coffin plates) from burials in the crypt at Christ Church, Spitalfields, in London. No investigation of the KV55 body, which includes examination of the bones (for example, the fusion of the epiphyses) and teeth, has led to agreement. Since many Egyptologists are disinclined to accept any of these unpalatable truths except where to do so allows them to refute someone else’s theory, the result has been a ceaseless and wholly unresolvable controversy about the KV55 body and other human remains from this period.

Presumed coffin of Akenaten.

Hans OllermannAnyone who starts reading the relevant literature in depth will be confounded by the claims and counter-claims which are driven almost entirely by a personal preference for Akhenaten or Smenkhkare. Consequently, none of the information (such as it is) yielded by the body can be tied conclusively to either candidate. Nor does any of the physiological or DNA evidence affect the view that whether the body is Akhenaten’s or not, it would still be the case that Akhenaten is the strongest candidate for the original burial in KV55 along with Tiye, and that Tutankhamun was most likely Akhenaten’s son and the one who reburied him in the Valley of the Kings in KV55.

Like a gun without a serial number, the anonymous body in KV55 only leads back to itself. The evidence needed to answer the question conclusively has either not survived or has not yet been found. After all, the whole intention was to deny the body its identity, a job that was done very efficiently and that tells us a great deal on its own. Moreover, when the tomb was found it housed only the remnants of a cache. We have no idea what else it once contained. Clearly there is something very wrong either with our understanding of what might have happened or the nature of the body, or both. Another mistake is to assume that the family relationships and the identities of the bodies were all correctly known to those involved in the original extractions from the Royal Tomb at Amarna and the reinterments in KV55, Tutankhamun himself, and especially those responsible for the subsequent removals and rearrangements. Therefore, the endlessly recycled arguments in favor of the body being either Akhenaten or Smenkhkare have gone everywhere and got nowhere.

A composite photograph of busts of Tiye and Akhenaten showing their remarkable similarity. The vertical dimension of the Akhenaten bust has been slightly adjusted to reduce its distorted proportions.

Pegasus BooksThose obsessed with KV55’s human remains consistently miss the point, which would be to ignore the body and concentrate instead on what the original assemblage was supposed to be. The mistake has always been to believe that an anonymous skeleton is the key to the history of this confusing episode. It can never be so. KV55 was apparently part of the wider effort under Tutankhamun to shut down Amarna by reburying the remains of Tiye and Akhenaten, and possibly others with them, in the Valley of the Kings. This clandestinely honoured tradition and protected the bodies from being robbed and desecrated had they remained at Amarna. It was a sensible precaution and means that there were probably other reburials elsewhere, for example of the deceased daughters of Akhenaten, which have never been found and may no longer exist. The subsequent partial clearance of KV55 and erasure of the remaining body’s identity have only served to divert attention from the original historical context of the deposit, apart from showing that the body was that of a prominent male member of the royal family in the Amarna period whose identity had to be obscured in perpetuity.

*

Anyone who chooses to pursue the musical-tombs story of KV55 will find that the arguments say far more about Egyptology than they do about the events and personalities enshrined in what was left of its rotted contents. The short period between Akhenaten’s death and Tutankhuaten’s accession injected only a minor delay in ending the Amarna period. For all the talk of graves, of shrines, and epithets, the child Tutankhuaten was so far as we know the only dynastically eligible royal male left to fill Egypt’s hollow crown. His accession secured the regime’s hold on power, at least for the moment, and Amun was restored. This indisputable turn of events rendered the possible fleeting tenure of the throne by any intermediaries, regardless of their order (or even attempting to rule at the same time) or who they were, during the last part of Akhenaten’s reign and its immediate aftermath neither here nor there.

The crisis was, however, only just beginning. The overwhelming issue was whether as Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun the new king and his young queen would live long enough to secure the dynasty’s future and maintain the grip on power that had already lasted well over two centuries. In that endeavor they were to fail.