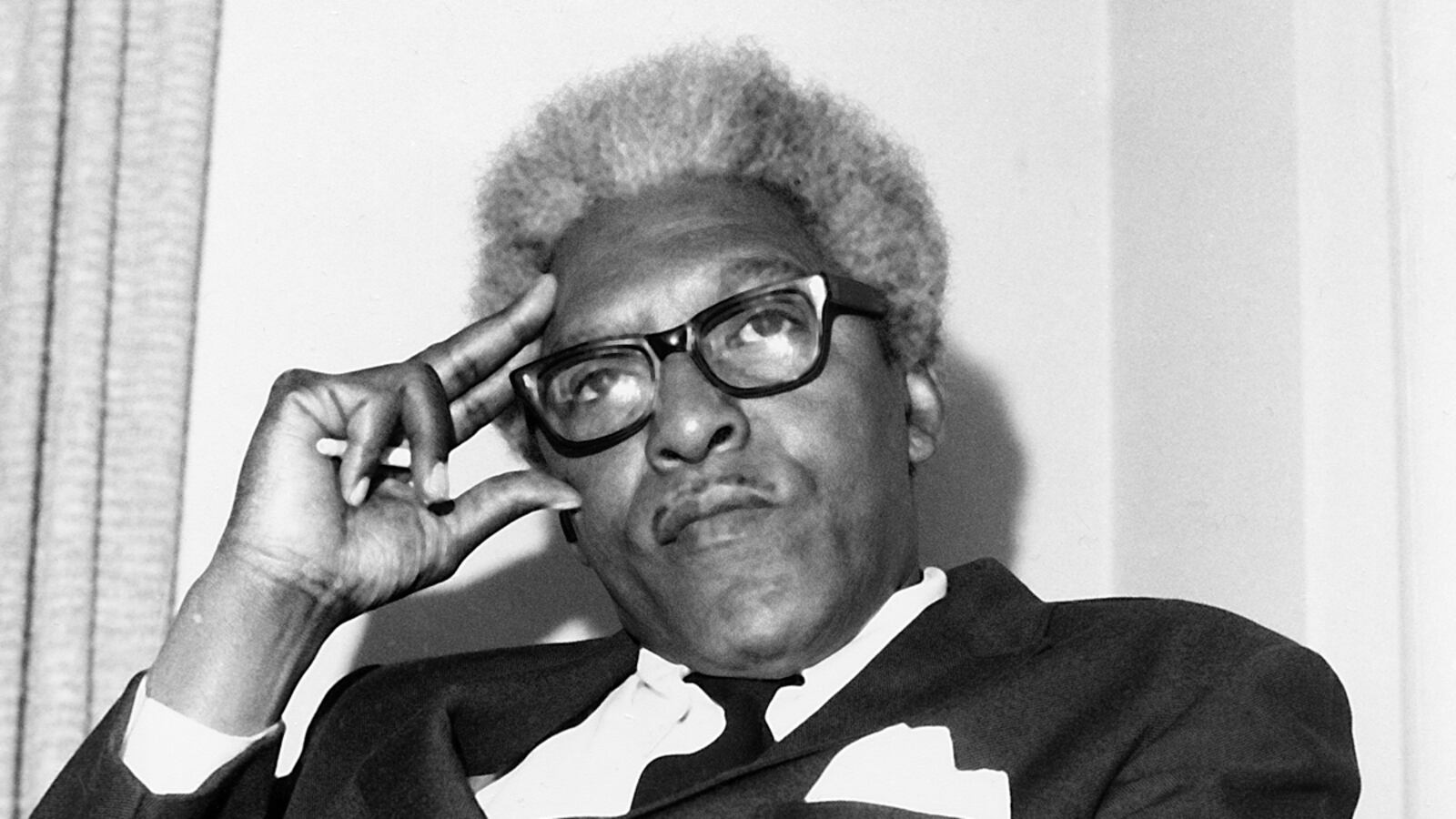

Martin Luther King, Jr. … Malcolm X … Jesse Jackson … Bayard Rustin …

Bayard Rustin?

If the name gave you pause, you’re not alone. Rustin was a central figure in the civil-rights movement, yet most people haven’t heard of him. A long-time pacifist, Rustin was the principal organizer of the 1963 March on Washington—which culminated in King’s historic “I Have A Dream” speech—and he developed much of the strategy utilized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and by activists on the battlefields across the South.

But all these contributions went largely unrecognized at the time, and they remain so today, for one main reason: Rustin was openly gay.

From the privacy of his Greewich Village apartment, where he sat closeted in virtual anonymity, Rustin introduced the concept of non-violent civil resistance to the battle for racial equality. He had recently returned from India, where he met with leaders of the Gandhian movement. Knowing that his sexual orientation would have been a distraction from the causes of racial and social justice he was fighting, Rustin spent his time in the background.

His story becomes all the more poignant in light of President Obama’s recent “evolution” on the issue of same-sex marriage. A key question has been whether Obama’s endorsement would trigger a backlash from the more conservative members of the black clergy, cutting into the president’s overwhelming support among African-Americans and endangering his reelection prospects.

The fact that this is a question in the first place highlights a sad reality: After Dr. King’s assassination, the civil-rights movement stalled.

The reasons for the stall were varied. For one thing, it became harder to identify racist targets when the more blatant forms, such as segregated seating and voting discrimination, were conquered. As individual and institutional racism became more subtle and sophisticated, different strategies were needed.

Jesse Jackson, along with younger activists, realized that the way forward was to embrace new groups that were forming to demand equal justice—groups such as the National Organization for Women, the American Indian Movement, and later, gay-rights groups.

But the older, more patriarchal members of the black clergy, who still held tremendous sway over the direction of the movement, lacked the far-sightedness, clarity of thought, and understanding of fairness for all that Dr. King exemplified. Even as lay leaders of the movement—such as union leader A. Phillip Randolph, James L. Farmer Jr. and Norman Hill, and Stokley Charmichael—openly embraced Rustin for his brilliance and unwavering commitment to the cause, Dr. King was one of the few ministers to do so.

In the decades following the heyday of the civil-rights movement, black clergy slowly but steadily retreated into misogyny and homophobia, and the hard-won gains of those electrifying early years of the struggle began to dissipate.

For example, black preachers have, with very few exceptions, fought tooth-and-nail against females in the pulpit, so when NOW began making demands for equality, old-line civil-rights activists turned a cold shoulder, despite the fact that both groups had a common enemy and could benefit from a common front. In sermon after sermon, black clergy decried the exclusion of African-American women in the leadership of feminist organizations while ignoring the absence of women in their own churches’ hierarchy. Some even went so far as to suggest that any gains made on the gender front would come at the expense of minorities. The notion that justice is a zero-sum game, that any gains won by one group come at the expense of another, is nonsense.

And when gay-rights organizations came along and began demanding equal treatment, many members of the black clergy went apoplectic, fulminating from their pulpits that these groups were usurping the legitimate tactics of the black civil-rights movement for foul purposes. That these were our strategies, and ours alone. The irony was that the black clergy had quit using those tactics against the legitmate enemies of black progress and instead focused their ire on homosexuals.

Like reactionary religious leaders the world over, the black clergy took (and still take) extreme umbrage at any questioning of their motives, tactics, and theology. One of the primary methods clergymen use to deflect criticism is to make it appear that anyone questioning them is actually questioning the word and will of God. But their selectivity in applying scripture shows the depth of their hypocrisy.

Fortunately, this generation is in decline, and their self-serving bumbling has far less impact today than when they frittered away the gains of the 1950s and ‘60s with their backward thinking.

Conservatives, by definition, strive to prevent change (when they are not attempting to roll back the clock), and yet everything the civil-rights movement achieved was at its core about change. So how can members of the black clergy now be for the status quo? Maybe keeping someone like Bayard Rustin in the shadows seemed to make sense at the time, but no one can argue that now.

Rustin himself understood the true breadth of the civil-rights movement. In a 1986 speech, he asserted, “Today, blacks are no longer the litmus paper or the barometer of social change. Blacks are in every segment of society and there are laws that help to protect them from racial discrimination. The new ‘niggers’ are gays … The question of social change should be framed with the most vulnerable group in mind: gay people."

Of course, conservative preachers would never give back the civil-rights gains made by an earlier generation simply because a gay man played a large role in making them happen. But still they find a way to conveniently overlook or deny the fact of his sexuality, as they do with, say, their gay choir directors who put so many butts in the pews—and cash in the collection plates—every Sunday morning.

With his support of gay marriage, President Obama has opened a new door in the ever-expanding universe of civil rights. Bayard Rustin did not live to see the day—he died in 1987—but he could have walked proudly through that door as both a black man and a gay man. We now have a profound responsibility to drag these reactionary black men of the cloth through it too, even if they are kicking and screaming all the while.