Just in time to spoil the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the publication of the Pentagon Papers, the Obama Justice Department is trying to do what Richard Nixon couldn't: indict a media organization.

A grand jury investigation into WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange under the Espionage Act and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act is underway in Alexandria, Virginia. The Justice Department has already subpoenaed the electronic records of many former WikiLeaks volunteers and at least three people have now been subpoenaed to testify in a case that could potentially criminalize forms of investigative journalism.

Many comparisons have been made between the Pentagon Papers and WikiLeaks, and most have focused on the landmark decision in New York Times v. United States that essentially banned prior restraints—or censorship orders—on the press. But long forgotten in Nixon's war on the press is an equally dangerous legal maneuver: Nixon convened a grand jury to indict the New York Times and its reporter, Neil Sheehan, for conspiracy to commit espionage—the same charge Obama's Justice Department is investigating Assange under today.

In 1971, after Nixon had lost the Pentagon Papers case in the Supreme Court, he desperately wanted to bring criminal charges against the Times. Attorney General John Mitchell first went to U.S. Attorney Whitney North Seymour Jr. in New York and asked him to indict the Times. When Seymour refused, a grand jury was convened in Boston, where the prosecutors eventually dragged virtually every journalist and anti-war academic in the Cambridge area to court using subpoenas. The Justice Department wanted to know exactly who knew of the Pentagon Papers before they were released and how they ended up at the New York Times.

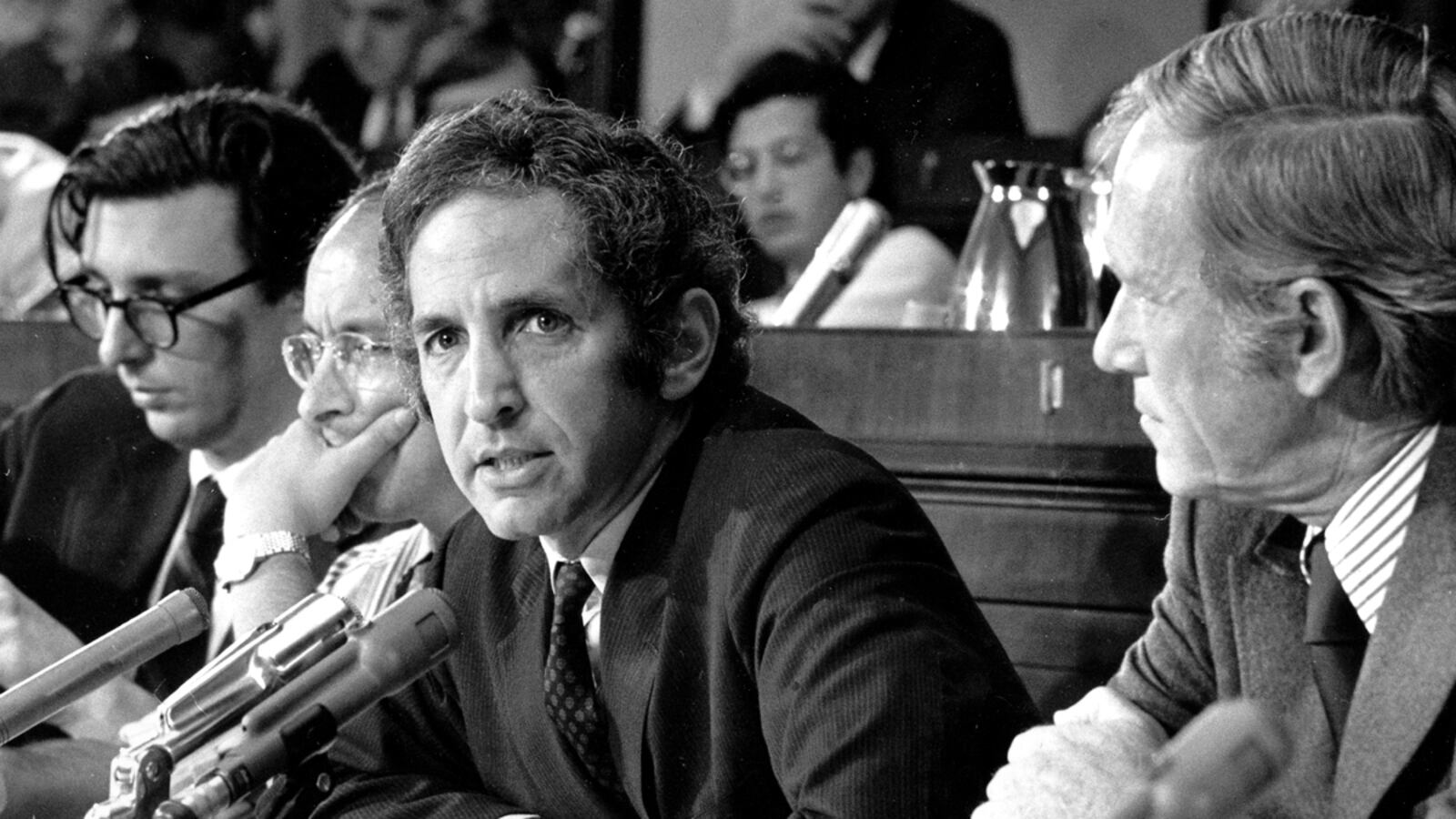

The government's "conspiracy" theory centered around how Sheehan got the Pentagon Papers in the first place. While Daniel Ellsberg had his own copy stored in his apartment in Cambridge, the government believed Ellsberg had given part of the papers to anti-war activists. It apparently theorized further that the activists had talked to Sheehan about publication in the Times, all of which it believed amounted to a conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act.

Sheehan's wife, Susan, a reporter for The New Yorker, also was named in the government's case before the grand jury. A Who's Who of Boston-based reporters and anti-war activists were then forced to testify, including New York Times reporter David Halberstam, anti-war activists Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, and two senatorial aides to Mike Gravel and Ted Kennedy. Harvard Professor Samuel Popkin would even serve a week in jail for refusing to testify as to his sources, citing the First Amendment right to keep them confidential.

The grand jury investigation lasted more than a year and the Times was so sure Sheehan would be indicted that a statement was drawn up for Times Publisher Arthur Sulzberger that read in part, "The indictment of Neil Sheehan for doing his job as a reporter strikes not just at one man and one newspaper but at the whole institution of the press of the United States. In deciding to seek Mr. Sheehan's indictment, the administration in effect has challenged the right of free newspapers to search out and publish essential information without harassment and intimidation."

But thanks to the efforts of many First Amendment lawyers and the witnesses' outright refusal to testify as to their knowledge of the Pentagon Papers, this statement never had to be issued. The government was eventually forced to dissolve the grand jury once it became clear it would be impossible to indict.

The same scene is playing out in a grand jury room in Alexandria today. Julian Assange is being investigated for conspiracy to commit espionage for allegedly speaking with the purported leaker, Bradley Manning. Chat logs between Manning and FBI informant Adrian Lamo suggest the two did converse at one point, and if the logs are to be believed, they may have talked about the WikiLeaks disclosures.

This, however, should not matter. Journalists communicate with sources all the time, regularly persuading them to leak. The First Amendment has long protected the transmission of information to journalists—even stolen information—as long as the journalist did not help commit the theft. Just as it protected Neil Sheehan in receiving the Pentagon Papers, it protects Julian Assange in receiving the WikiLeaks files, and neither should have to worry about being indicted for, as Sulzberger said, "doing their job as a reporter."

If an indictment and conviction of Assange were ever to be achieved, the courtroom scenes from that grand jury room 40 years ago could become commonplace. Not only would reporters be hauled in and questioned ("Did you write this to hurt U.S. foreign policy?" "Are you anti-war?"), but other reporters, not even assigned to the story, would be dragged in as well. Halberstam and the like did not have possession of the Pentagon Papers, but they were still subpoenaed just to find out if they knew who had them.

Charging Julian Assange with "conspiracy to commit espionage" would effectively be setting a precedent with a charge that more accurately could be characterized as "conspiracy to commit journalism."