Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a sexually transmitted disease that causes head, neck, anal, and genital cancers. Currently, about 79 million Americans, most in their late teens and early twenties, are infected with the virus. The annual statistics are grim. Every year in the United States:

• 14 million people are newly infected with HPV.• 19,000 women and 8,000 men develop HPV-associated cancers.• 5,000 people die from cancers caused by HPV.

That’s the bad news.

The good news is that a vaccine is available to prevent it. In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed an HPV vaccine that will prevent about 70 percent of the cancers caused by this virus; in 2016, the vaccine was replaced by another HPV vaccine that will prevent about 85 percent. The HPV vaccine is now recommended for all girls and boys between 11 and 13 years of age. Unfortunately, although the vaccine has been around for more than 10 years, most teenagers don’t get it. Only about 45 percent of girls and 25 percent of boys have completed the recommended series.

Given current immunization rates, every year in the United States about 2,000 boys and girls are condemned to die from cancer because they haven’t received an HPV vaccine—a remarkable public health failure.

The HPV vaccine isn’t the only vaccine recommended for teenagers in the United States. Vaccines to prevent tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough, and meningococcus (a cause of meningitis and bloodstream infections) are also part of the routine schedule. Unlike the HPV vaccine, however, the uptake of these other vaccines is excellent, in the 80 to 90 percent range. Given that the HPV vaccine will prevent more suffering and death than all four of these other vaccines combined, why are immunization rates for HPV so low? The answer: sex.

The HPV vaccine prevents but doesn’t treat HPV infections. Therefore, in order for the vaccine to be effective, it has to be given before children have sex. For some clinicians, this makes for an uncomfortable conversation in front of young teenagers and their parents. But there’s another more subtle force at work.

After the FDA licenses a vaccine, the company that makes it can sell it. Usually, however, the manufacturer and insurance companies wait to see what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommend. The committee that advises the CDC on these recommendations is called the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), which consists of experts in the fields of immunology, virology, vaccinology, epidemiology, microbiology, statistics, and infectious diseases. I was a member of the ACIP and later of ACIP working groups when the issue of the HPV vaccine first arose. ACIP meetings are open to the public. Anyone can step up to the microphone and comment. One group that I had never heard of, but that made its voice loud and clear during the committee hearings, was Focus on the Family.

Focus on the Family, like several evangelical organizations, rose to prominence in the 1980s. It’s stated mission is “nurturing and defending the God-ordained institution of the family and promoting biblical truths worldwide.” Focus on the Family promotes creationism, school prayer, and traditional gender roles. Relevant to its appearance at the ACIP meetings, Focus on the Family also opposes pre-marital sex and supports abstinence-only sex education. The logic is clear. If people don’t have sex before they are married and are faithful to their spouse throughout their marriage, then neither partner will ever contract a sexually transmitted disease. While true, this situation describes a very small percentage of the American public.

Representatives from Focus on the Family who testified at the ACIP hearings feared that if the HPV vaccine were universally recommended, adolescents would be encouraged to be sexually promiscuous. For several reasons, this didn’t make much sense. First, the HPV vaccine doesn’t prevent other sexually transmitted diseases, like chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes, and syphilis. Second, the HPV vaccine doesn’t prevent all strains of HPV, just the ones that are most likely to cause cancer. Third, the HPV vaccine, like all vaccines, isn’t 100 percent effective; preventing about 95 percent of infections caused by the strains contained in the vaccine. This means that about 5 percent of vaccine recipients won’t be protected. Frankly, the logic argued by Focus on the Family was akin to believing that after receiving their tetanus vaccine, teenagers would feel free to run across a bed of rusty nails with impunity.

Nonetheless, the fear of promiscuity raised by Focus on the Family was sufficient to cause researchers to study it. In November 2012, Robert Bednarczyk and coworkers at Emory University in Atlanta examined 1,400 girls who either had or hadn’t received the HPV vaccine. They found that sexual activity-related outcomes—like pregnancy testing, contraceptive counseling, and testing for or diagnosing sexually transmitted infections—was the same in both groups. Despite the concern raised by Focus on the Family, the HPV vaccine hadn’t freed teenagers to engage in promiscuous sex.

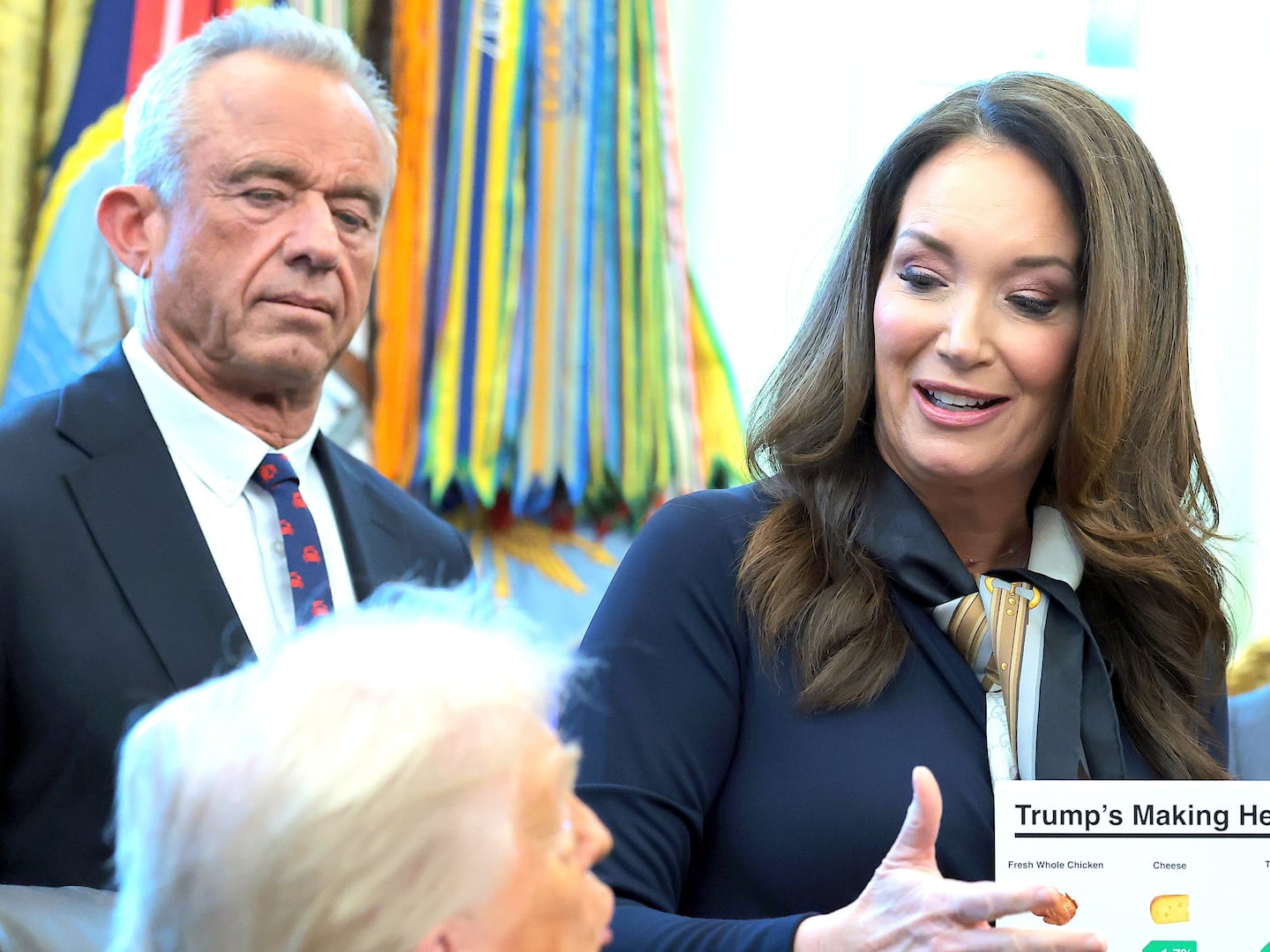

I hadn’t heard about Focus on the Family again until recently. It was during the confirmation hearings for Betsy DeVos, Donald Trump’s pick to head the Department of Education. According to watchdog groups, the Edgar and Elsa Prince Foundation gave at least $5 million to Focus on the Family. Edgar and Elsa Prince are Betsy DeVos’s parents. For 17 years, DeVos has been listed as a vice president of her parents’ foundation.

Because Focus on the Family also opposes the rights of the LGBT community, DeVos was asked about this association during her confirmation hearing. She claimed that the tax forms listing her as a vice president were a “clerical error”—a 17-year clerical error. One can only hope that DeVos’s personal beliefs will not affect how the Department of Education approaches sex education in public schools, especially regarding a common cancer-causing disease and a vaccine that could prevent it.

Paul A. Offit, MD is a professor of pediatrics and director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He is the author of Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All (Basic Books, 2011).