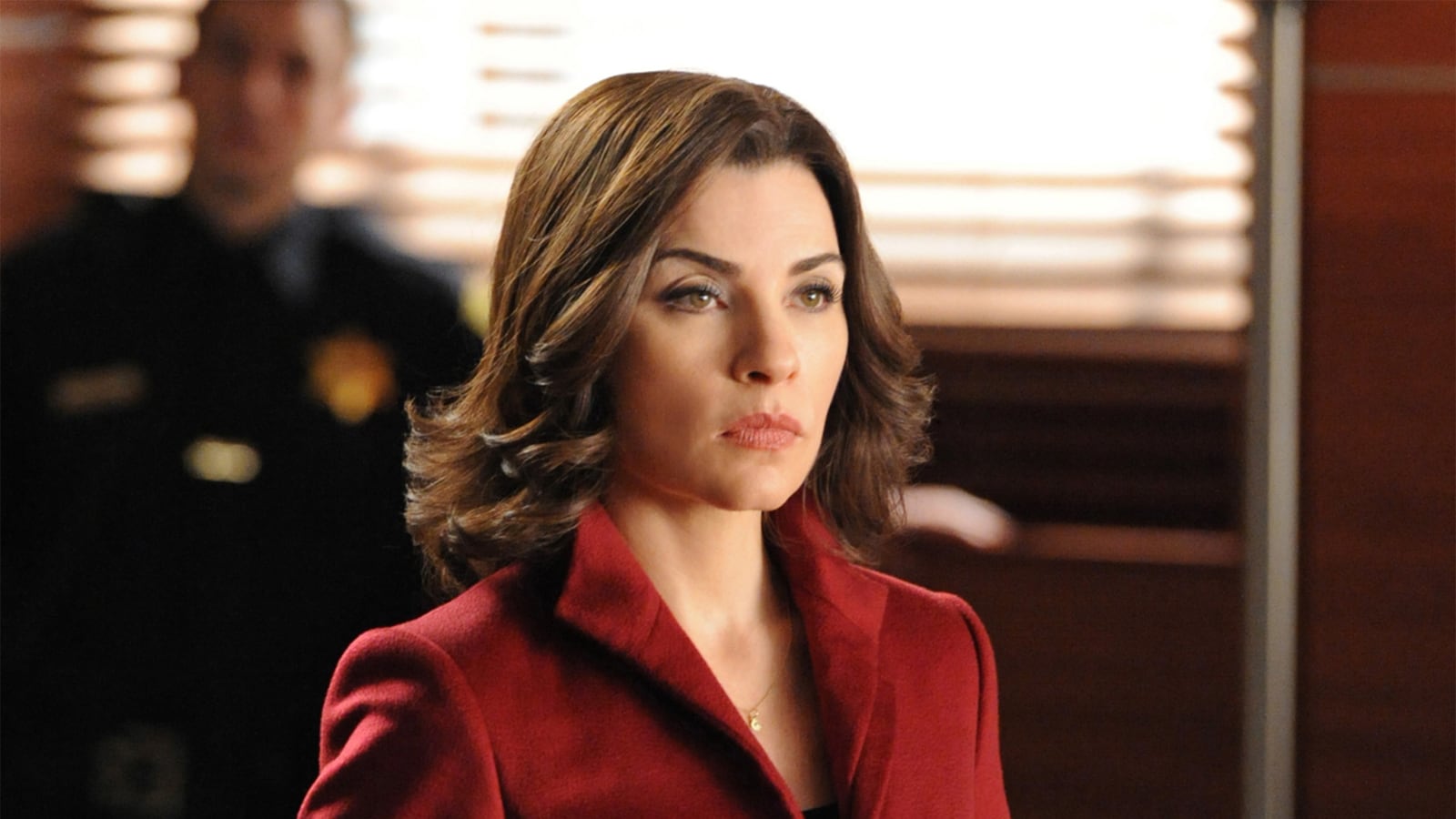

So Alicia Florrick, the long-suffering title character of The Good Wife, finally took the plunge and decided to run for office herself. Florrick’s decision, taken after she was encouraged to do so by the likes of Gloria Steinem and Valerie Jarrett in cameos, should make for good television, but it flies in the face of the reality of many real-life women, who are still much less likely to run for office than men. Like Florrick, these women are more likely to have a litany of reasons why they feel they can’t run or don’t want to.

But Florrick’s move raises a new question: Can depictions of women as candidates and leaders in film and television increase the number of women and girls who aspire to leadership roles?

Julie Burton, president of the Women’s Media Center, an organization devoted to monitoring the images of women and their impact on culture, told me: “Television has great cultural and economic power. It tells us who we are and what our roles are in society.” Burton says she is excited by some of the recent depictions of women as leaders and candidates, but they are still “the exception.” She concluded, “If the standard TV image of a politician is a man, women—and importantly, girls—won’t see themselves in that picture and won’t aspire to those positions. That’s a loss for everyone.”

Research substantiates Burton’s concerns. A study published last year in Political Psychology found that the physical traits people are most likely to ascribe to women, including beauty or compassion, are not traits they tend to ascribe to female political figures. Even more noteworthy, female politicians were also not likely to be ascribed the positive traits that were ascribed to men in general and male politicians, such as competence, competitiveness, and overall leadership capability.

These findings may not seem quite so surprising when considering a five-year analysis of the 500 top grossing films from 2007 to 2012. This analysis found that female characters were both underrepresented and under-clothed when they did appear. According to Stacy Smith, of USC’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, “2012 featured the lowest percentage of female speaking characters across the years studied.” It further noted that “looking at all female speaking characters, approximately a third are shown in sexually revealing attire or are partially naked in 2010 and 2012. The trend is more pronounced with regard to teens, as over half are shown sexualized in the most recent year evaluated in this study.”

It’s easy to understand why a survey group would not ascribe traits like “competency” and “strong leader” to women when the images of women we are bombarded with don’t embody those characteristics. Which is why so many women interviewed for this piece are celebrating the increasing number of strong female characters on television on programs like Madam Secretary, Scandal, Veep, and of course The Good Wife.

“It matters to see those images—greatly,” says Marie Wilson. The former president of the Ms. Foundation, Wilson is best known for creating Take Your Daughter to Work Day. She has been one of the feminist movement’s most vocal proponents of using popular culture to educate the public and advance gender equality— something that did not always endear her to her peers, many of whom view legislation and protests as the most effective vehicles for social change.

“Take Your Daughter to Work Day was when I first realized we had created something at the Ms. Foundation that was going to make change by getting into the culture,” she explains. “The thing that first made me cry was I turned on the television the morning of Take Your Daughter to Work Day and I saw little girls standing behind the camera on the morning-show sets.” Camera operators have traditionally been men. Many had brought their daughters that day.

Wilson later landed in hot water with some by pushing for the creation of the first Barbie for President doll. Barbie had long been the nemesis of the feminist movement, but Wilson said some of the antipathy lifted when, at a women’s event the year of the doll’s high profile debut in 2004, a room full of young women rose to their feet and cheered Presidential Barbie. “Wilma Mankiller [the late Native American Chief] used to say ‘When you want to make change, you start where the people are, not where you are,’” Wilson says. “And I got it.”

After founding The White House Project in 1998, Wilson worked with Melissa Silverstein of Women and Hollywood to encourage those in film and television to create more substantive depictions of women as leaders. Commander in Chief, starring Geena Davis as the first female U.S. president, premiered in 2005. But in the decade since it aired, America has still not elected a female president and the number of women running for office is still not on par with men.

But the numbers are on the rise.

A record 20 women are serving in the U.S. Senate, and according to organizations that track women in politics, the upcoming election features more mothers of young children running for office than ever. Historically, women who ran for office waited until their children were nearing adulthood, but there are at least 12 viable female candidates this midterm election cycle who have small children.

Jess McIntosh, a spokeswoman for Emily’s List, believes that the influence of culture can take time to manifest. She referenced the number of twenty-something and thirty-something women now working in politics, particularly behind the scenes like she does, who have cited watching The West Wing during their high school and college years as inspiring their career paths.

“It’s clear that pop culture representations have real-world impact,” McIntosh said. “The number of women going into forensic science spiked after CSI became popular.” But McIntosh also explained that it takes more than one show or one moment to shift attitudes. “You can’t attribute President Obama’s win to Morgan Freeman playing a president [in Deep Impact] that one time. You have to have several examples and touchstones to shift culture—not to mention the right real-world candidates. It takes some time for an idea to really capture the cultural zeitgeist.”

Most of the experts interviewed for this piece stressed how much more likely women are to run for office if they are asked—just like Alicia Florrick. Erin Vilardi founded the organization VoteRunLead, which just launched Invitation Nation, a campaign to encourage all women to nominate a woman, or two or three to run for office.

In an email, Michelle King, executive producer of The Good Wife, wrote to me: “As Gloria Steinem says to Alicia, more good women need to run for office. So if there were a smart, informed, and accomplished woman who was inspired to run by the show, we’d be delighted.”

According to Smith’s research on representations of women on screen, one of the greatest predictors of whether women will be depicted in an empowering way is whether there are women behind the scenes influencing how stories featuring women are told. While King has shepherded The Good Wife, Commander in Chief was championed by ABC executive Anne Sweeney. So maybe in addition to seeing more female candidates on screen, we should focus on making sure more women and girls follow in Sweeney and King’s footsteps.