Forty years past, world politics were churning with a vicious Vietnam War reaching its crescendo and with the great powers—the United States, the Soviet Union, and China—stumbling toward confrontations, when suddenly, diplomacy repositioned the stars in the international heavens. Most improbably, it seemed, President Nixon journeyed to China to palaver with Mao Zedong, and most central matters on the world stage changed: the opening to China transformed the global playing field, giving Washington new and substantial leverage over both Moscow and Beijing and smothering many of the ill-effects of the Vietnam War becoming a lost cause. One of us, Winston Lord, participated in these critical events as a close adviser to National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger; the other of us, Leslie Gelb, was to write about this diplomatic tour de force for decades to come.

This story seems light years removed from today’s boiling pots, from the war torches being lit over Iran, the American withdrawal process from Afghanistan, the upheavals of the Arab Spring, Europe’s economic travails, and of course, events within China and between China as a world power and the United States. But it is not. The way Nixon and Kissinger thought about the opening to China and the way Mao responded encase maxims of diplomacy that could well help to prevent these stars from colliding 40 years after Nixon’s historic visit.

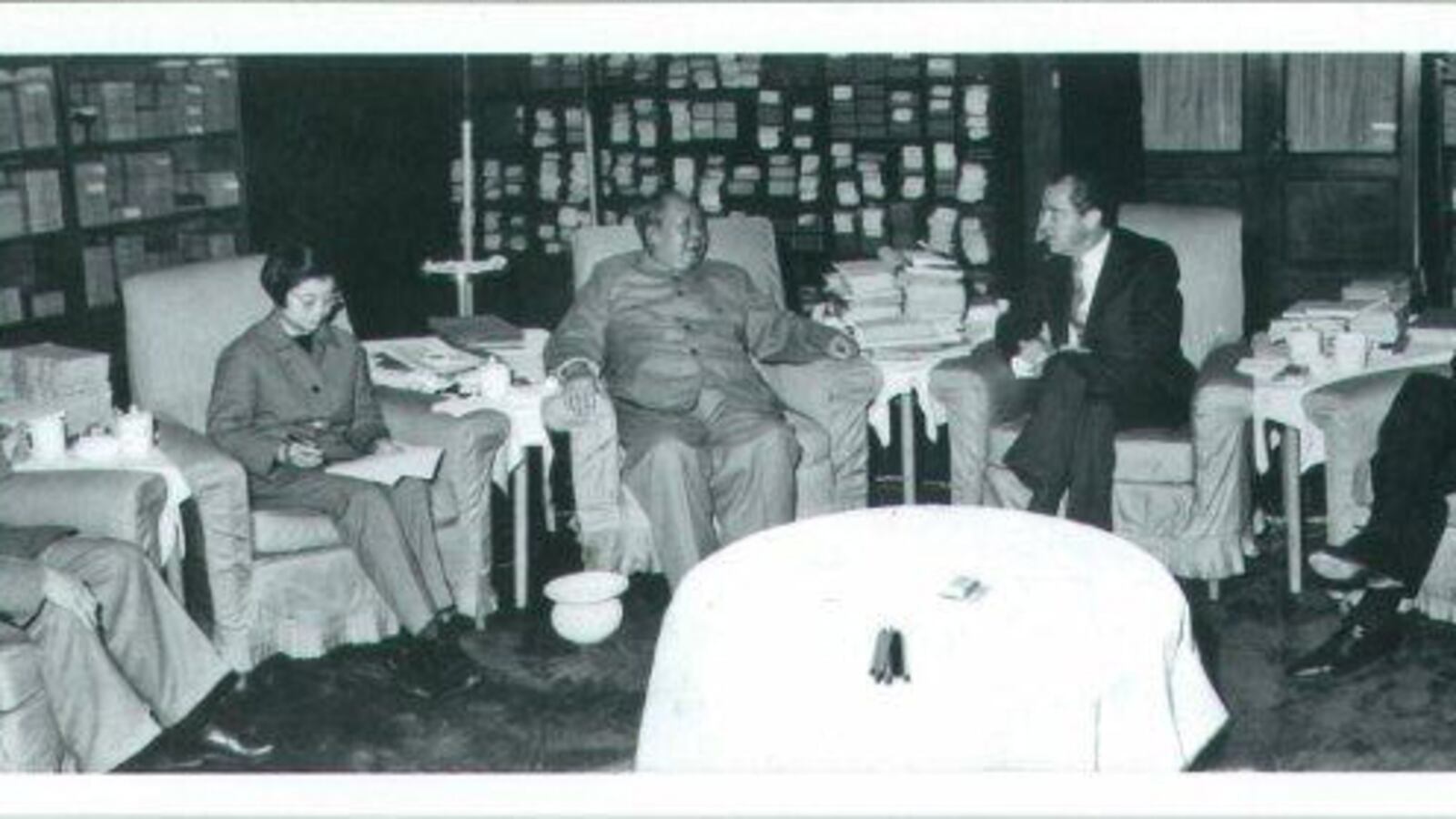

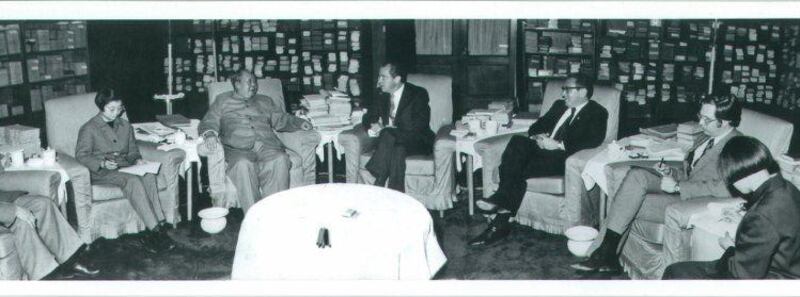

The famous summit occurred Feb. 21-28, 1972. But it had a legendary prequel in Kissinger’s secret flight to Beijing the year before. Vanishing from Pakistan on a Pakistani flight to China, with Lord and two others, he laid the groundwork for the summit to come.

At one of the summit’s banquets, Nixon toasted the meeting as “the week that changed the world.” For once, this hyperbole was justified. It is not an exaggeration to think of this summit as one of the three or four most momentous geopolitical earthquakes since the second World War.

The world’s most powerful and populous countries had warred in Korea and were locked in 22 years of mutual isolation, threats, and hostility. Notably, the Chinese had recently skirmished with the Soviet Bear on its northern border and were alarmed at the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia under the “Brezhnev Doctrine,” whereby Moscow asserted its right to police the communist world. In the throes of its convulsive Cultural Revolution, with exactly one ambassador permitted overseas, Beijing was totally isolated. The U.S. struggled globally with the USSR, searching with scant success for a more stable relationship between two nuclear superpowers. Shaken by violent demonstrations, assassinations, and race riots, America was mired in a long, messy, controversial war. And remember, any simple recounting of the world situation doesn’t begin to capture the turmoil and uncertainty in world politics.

The initiative was far from an easy call for Nixon, though he was an established hawk and anti-communist. It still took great courage to break the ice. Public opinion was fiercely hostile toward the “Red Chinese” and very protective of Taiwan, which Beijing considered part of China. Also, Nixon had no assurances of a breakthrough in Beijing. Such a trip to the Middle Kingdom could well have ended in a geopolitical and political fiasco.

Instead, it was a triumph. The leaders all allowed themselves to be photographed toasting and shaking hands in a way that conveyed a great bridge had been crossed. There certainly was no air of final accomplishment, of fundamental matters being settled. If anything, quite the contrary. They gave the sense that they had talked long and hard, and had agreed that such exchanges served their nations’ interests far better than confrontation and war. The triumph was more a matter of the summit itself, of how it would realign the stars, global and political perceptions, and power relationships. In the last analysis, it was triumph because it set a startling new relationship in motion.

Here is why the Chinese-American summit, though it did not resolve any major disputes, is a triumph and fertile territory for present diplomacy:

First, the two sides understood that minimal advance assurances were needed to inoculate the meeting against a debacle. Secret messages via Pakistan and the secret July 1971 Kissinger trip assured this.

Second and to repeat, it took courage and imagination—vision, if you like. Both sides had to imagine how they could do this against their phalanx of political critics and manage the outcome, which threatened to be highly controversial.

Third, both sides had to think of the summit not as a chance for unilateral victory, but as a win-win game—and they did. It was a classic example of each countries’ serving the other’s primary goals. The Chinese won immediate security reinforcement against Soviet pressures. And they broke out of their diplomatic isolation: no longer blackballed by Washington, China also won prompt admission to the United Nations and diplomatic relations with key European and Asian countries.

The Americans won further containment of the USSR, and instant leverage that generated a Moscow summit, rapid progress toward a Berlin agreement, and a strategic arms control pact. Within the next year, there would thus be two summits and a negotiated end to the Vietnam War. Most important, despite domestic turmoil and foreign quagmire, Washington demonstrated its capacity for world leadership. Indeed, the opening to one-fifth of the world’s people placed in perspective and transcended the messy outcome of a war in the corner of Southeast Asia. It dramatically lifted the global stature of America and the morale of Americans.

Fourth, these seminal foreign policy and diplomatic accomplishments were made possible only because the two sides agreed to postpone resolution of the thorniest issues, most notably Taiwan. In other words, they were not going to let the most insoluble problems trump what could be achieved. This was a prerequisite for the trip because Nixon made clear in advance he would not abandon Taiwan, and the Chinese agreed to a broader agenda. In their meeting, Mao made explicit both his patience on Taiwan and animus against Moscow.

Fifth, the leaders figured out a way to conclude the meeting on a realistic note. It was Mao who had the brilliant idea, fleshed out during the Kissinger October 1971 preparatory trip, that the two countries should craft an unprecedented Joint Communiqué, free from the usual ambiguous language of pretended accord. Instead, the two sides presented their separate, colliding views on ideology, and issues before stating their agreed points of cooperation. The resulting Shanghai Communiqué was credible precisely because it did not paper over differences between enemies of two decades, while it highlighted areas of convergence, like the “anti-hegemony” clause directed at Moscow.

Most summit communiqués evaporate before the nightly news concludes. Forty years later, this one is still invoked as a fundamental guide to Sino-American relations.

One can imagine present applications of this diplomatic tour de force, most usefully with Iran. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton could meet secretly with President Ahmadinejad to ensure no disasters. President Obama, then, could fly to a third country meeting with Ayatollah Khamenei. They could agree to procedures in the Straits of Hormuz to prevent incidents from escalating. They could agree to stop Iranian uranium enrichment where it is, without ruling out future arrangements. Tougher inspection regimes could be established. Full resolution of the issue could be left for the time being. At a minimum, the situation would be frozen, and the two sides would not continue to talk themselves into a war.

While most of the techniques employed in the China opening apply especially to Iran, the boldness and creativity of the Nixon move can be instructive elsewhere. It might be time for elaborate diplomacy in South Asia. The U.S. is gradually departing, and the fact is Afghanistan’s neighbors have far more interest in what happens next than do Americans. It’s for them, mainly, to do something about extremists, drugs, and refugees.

It’s past time for a comprehensive proposal to tackle Arab-Israeli disputes. Otherwise, these two peoples are bound to be swept away by the tumultuous and unpredictable Arab Spring.

Such convulsions cannot be tamed by military might. They can be drained and readied for future resolution. They can be sapped of war fever by the diplomatic courage and genius displayed by Kissinger and Nixon four decades ago.

Winston Lord, Henry Kissinger’s closest aide, accompanied him and President Nixon to all the China opening meetings. He later served as U.S. ambassador to China from 1985 to 1989. A full accounting of these events can be found in Lord’s State Department Oral History at the Library of Congress website.

Leslie H. Gelb was diplomatic correspondent and columnist for The New York Times and is president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations.