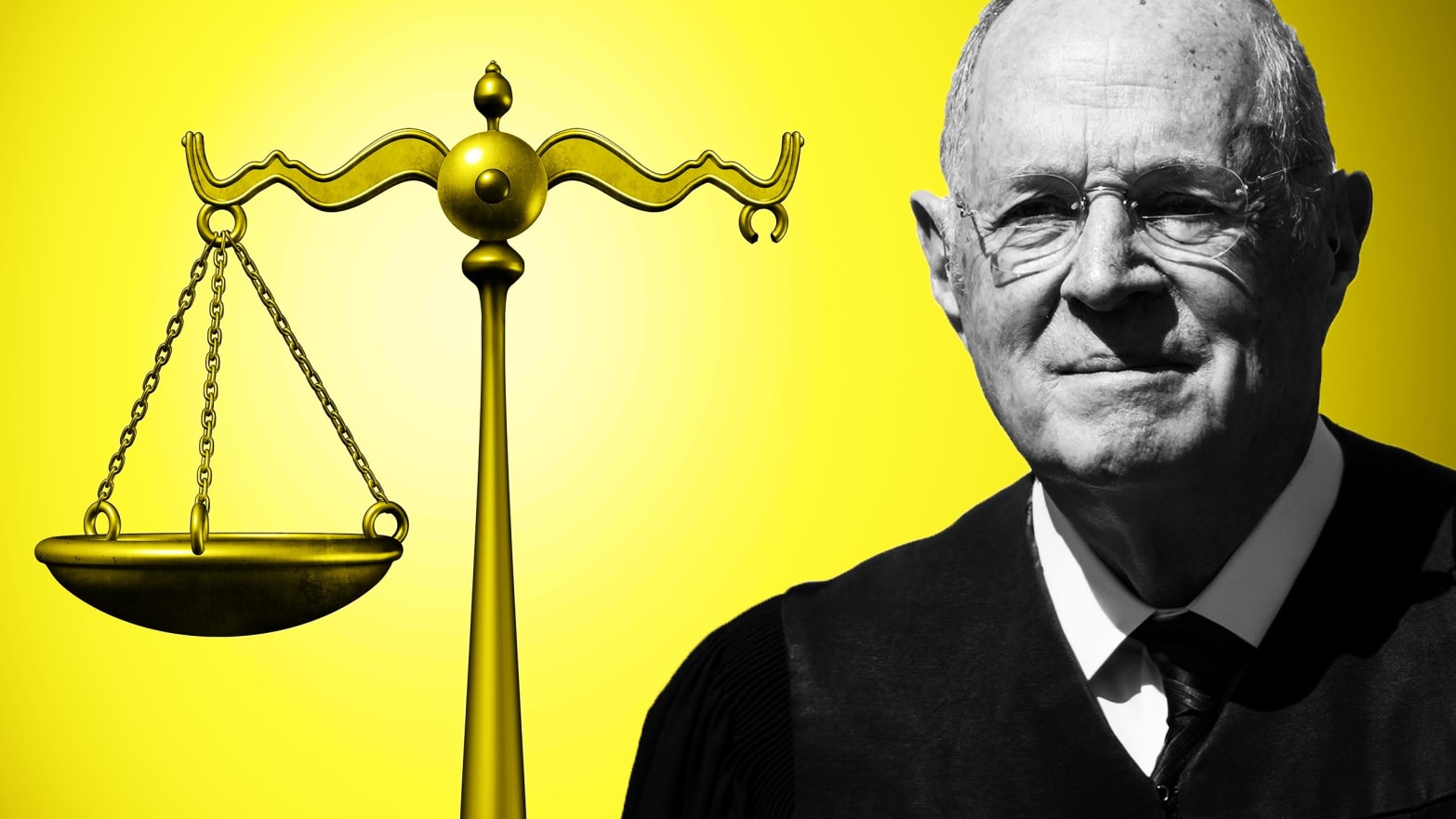

The judicial apocalypse is here, and there’s nothing Democrats can do to stop it. Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing voter in most of the Supreme Court’s close cases of the last decade, is retiring at age 81.

President Donald Trump will choose his successor.

With the Senate filibuster of Supreme Court nominees eliminated last year by Republican Senate Leader Mitch McConnell, anyone Trump nominates will be rubber-stamped. That has been the pattern so far, with 39 judges confirmed so far, often in an expedited process, with not a single Republican vote opposing any of them.

Moreover, Trump’s judicial nominees thus far have been chosen by the far-right Federalist Society, which has put forward extreme ideologues in the mode of Justice Clarence Thomas, whose ideas were once considered on the fringe but are now increasingly within the mainstream.

While Justice Neil Gorsuch replaced another conservative, the late Justice Antonin Scalia, whoever replaces Justice Kennedy will likely be a conservative firebrand replacing a moderate. The shift will transform the Court for decades to come.

Among the Court’s precedents that will be on the chopping block are Roe v. Wade, protecting women’s rights to choose to have an abortion, and Obergefell v. Hodges, protecting gay people’s rights to marry.

Roe has been significantly limited in recent years, and all four sitting conservative justices have either opposed it directly, or opposed the doctrines on which it is based.

Justice Kennedy wrote the Obergefell decision, over a vigorous dissent by Chief Justice John Roberts, and the vote was 5-4. Even the Court’s own doctrines of respecting precedent will not protect same-sex marriage; just this week, the Court directly overturned a precedent regarding public-section unions.

It is quite likely that the both rights will come to an end within two to three years: there are cases pending that would further limit each, and more will soon follow.

In the case of abortion rights, Justice Kennedy was the swing vote striking down Texas’s junk-science regulations that would have shuttered most abortion clinics in the state; with him gone, other states will surely pass and litigate their own versions. Iowa’s new law, known as the heartbeat bill, bans abortions once a heartbeat is detected, usually the sixth week of pregnancy – the lawsuit about that law will provide the next Supreme Court with an opportunity to further limit Roe, or overturn it entirely.

Likewise for marriage rights. There are already cases pending about whether same-sex spouses are entitled to spousal benefits, and numerous cases about when private actors may discriminate against gay people. Each of these provide opportunities to limit or overturn Obergefell.

Of course, Democrats will do everything in their power to fight this transformation. The trouble is, they have no power. They cannot stop Trump from nominating another Gorsuch-like extremist and cannot stop the Senate from confirming one. Assuming the Senate fast-tracks the nomination – as McConnell and Trump have already said will happen – the confirmation vote will take place before the November elections.

Democrats’ only hope is to somehow persuade moderate Republicans like Jeff Flake or Susan Collins to oppose Trump’s nominee, although they have been mostly unable to do in the first two years of the Trump presidency. (Senator Flake recently said he would block Trump’s nominees if the Senate did not act to restrain Trump on tariffs.)

Understandably, the consequences for the Supreme Court, and civil rights as we know them today, are eclipsing, for now, the fascinating arc of Justice Kennedy’s 33-year career on the Court.

Nominated by President Reagan in 1987, Kennedy was from the beginning a centrist candidate; he replaced the extremist Robert Bork, whose nomination failed in the Senate. And indeed, Kennedy sided with both liberals and conservatives, depending on the issue.

He was part of the Court deciding Bush v. Gore and effectively anointing George W. Bush as president, and part of the majority in Citizens United, which opened up the spigot of corporate and dark money into politics. In just the last month, he joined with the Court’s conservative majority in upholding Trump’s travel ban, busting public sector unions, and allowing extreme gerrymanders in Texas and Wisconsin.

But it is for Justice Kennedy’s substantively liberal decisions that he is probably be best remembered.

In 1992, abortion rights activists and opponents thought that Roe v. Wade was about to be overturned, but Justice Kennedy joined Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in a middle-of-the-road opinion that affirmed Roe but allowed states to regulate abortions so long as the regulations didn’t place an “undue burden” on women seeking them.

And Justice Kennedy turned out to be the unlikely hero of the LGBT equality movement, writing every major pro-LGBT opinion in the Supreme Court’s history, culminating in Obergefell in 2015.

Justice Kennedy has his fair share of detractors among legal scholars, as his case-by-case approach to decision-making can be understood either as a salutary judicial minimalism or as an infuriating inability to make and state the law. The rap on Justice Kennedy is that after he writes an opinion, you’re not much clearer about the law than you were before he wrote it: you know the application of the law to a specific case, but his fact-based reasoning provides little clear guidance for future cases.

Justice Kennedy’s cases on affirmative action, and race in general, are probably the best example of this, and they have led to tremendous uncertainty, and a standard that basically states that race can be used somewhat in college admissions, but not too much – a standard that is not really a standard at all.

Even his same-sex marriage decision isn’t entirely clear as to what, exactly, is the precise foundation of the right. Its soaring rhetoric inspired LGBT people (including this one) but its legal reasoning is confusing.

However, in this dark moment in American history, it is Justice Kennedy’s stature as a senior jurist able to bridge the two sides of the ideological aisle that will surely be immediately missed.

In an ideal world, a responsible Republican president would nominate a thoughtful moderate-conservative who is respected by his colleagues and who lies within the judicial mainstream – basically, a conservative version of Merrick Garland.

But in the world we live in, Trump is likely to please his base by nominating an extreme conservative, like his recent picks who have compared abortion to slavery, called Justice Kennedy a “judicial prostitute,” and called transgender children “evidence of Satan’s plan at work.” All of those nominees, by the way, were confirmed without a single Republican vote against.

It’s hard to think of a time when so much power was about to be transferred so unilaterally to the extreme edge of the ideological spectrum – and with so little power to resist it. That time is now here.