Hip hop is an amazing, life-transforming tool.

Hip hop saves lives. You don’t believe me? Ask Robert Fitzgerald Diggs.

Rap music is so much more than sound; the notes produced are typically a reflection of and a reaction to the environment from which it came. Furthermore, rap music is the sonic extension of hip-hop culture. Hip hop is language—spoken, written and visually represented via clothing, fine art and physical gestures. Hip hop, therefore, is identity. And when you consider what has just been laid out for you, the Wu-Tang Clan is indisputably the greatest rap group of all time. Don’t waste precious moments of your life trying to argue against the truth. Sit down. Relax your collar a bit. Stay a while.

OK.

Wu mastermind Robert “RZA” Diggs had a rough patch back in the early ‘90s. On one hand he ascended great heights: at 18, Diggs landed a record deal with noted label Tommy Boy. In the inner city at that time, the perception was, hey, if you had a record deal you were rich! But things went sour with the record he put out. RZA was at that point known as Prince Rakeem. Prince Rakeem’s single “Ooh We Love You Rakeem”—which essentially played up a false “ladies’ man” persona—didn’t connect the way Tommy Boy thought it would (they allegedly insisted on Diggs taking this approach). RZA was suddenly back on the ground, moving like a mere mortal with lint in his pockets.

About Diggs’ rough patch: that came in the form of an attempted murder charge. He had a pistol. He squeezed the trigger. Bullets pierced skin. This happened in Steubenville, Ohio. Home of Dean Martin—a dominion far, far away from Diggs’ native Staten Island, New York. Staten Island was known for the landfill that was once the highest point on the Eastern seaboard, and that’s about it. Oh, and a lot of cops and mobsters have traditionally lived there, too.

Diggs would go to trial and beat the case, which was a miracle and a half. Diggs was in Steubenville visiting his mother and was focused on making money on the streets while he was there because he was broke as fuck. But soon enough, he would overstay his welcome. There was no room for the cocky New York boy on the streets Steubenville, so Diggs decided to reinvent himself. He would live every day in a space that moved somewhere between real life and his dreams. Prince Rakeem would die, and RZA was born. During the car ride back to Staten Island, RZA vowed to make a radical change. His momma told him this was his second chance at life; that he shouldn’t squander the opportunity.

Enter the Wu-Tang Clan.

Twenty-five years ago, a group of friends rallied around a young Robert Fitzgerald Diggs. These friends mostly hailed from the housing projects of Staten Island, New York—most notably Park Hill and Stapleton. Robert was an emcee/producer with a vision and a powerful ear. He wanted so much more for himself and his family. Beating that case in Steubenville helped to fortify his positive mental attitude. He was going to go for it. Again. And this time, he was going to do it his way. He wasn’t interested in being another man’s slave. He vowed independence and preached it to the friends he assembled. These friends were essentially superheroes—hip hop’s answer to the X-Men. They wielded microphones and blasted their own language and poetry. Robert knew that the crew had something radical to offer. Ghostface Killah. Method Man. Raekwon the Chef. ‘Ol Dirty Bastard. U-God. Inspectah Deck. Masta Killa. Cappadonna. GZA. Together they would bring the motherfucking ruckus.

Hip hop would never be the same.

U-God was selling cocaine at the time. But RZA had a divine plan: he asked U-God if he would sacrifice a year of his life to pursue the rap dream. Something told U-God to quit selling cocaine and give RZA’s plan a chance. Most of the tracks on their debut album, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), didn’t feature U-God because he wound up going back to jail. It was a dream temporarily deferred. When he was released from prison, there was opportunity waiting for him—as RZA had promised. All he had to do was want that change for himself.

These young men were fostering something beastly on the underground rap scene. They trained and refined their collective voice while shaping their individual ones. People began to recognize. They made names for themselves. The collective would soon gain notoriety the world over as the almighty Wu-Tang Clan: the greatest rap group ever. If the 12 Apostles had bars they would be the Wu-Tang Clan. Enter the Wu-Tang was the Rap Bible.

The film/limited series that this scribe directed is called Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men (available on Showtime). An obvious nod to John Steinbeck’s masterful tome Of Mice and Men, our film’s title says it all: the Wu-Tang story is a classic American story. It’s about pain, struggle, strife, identity, self-esteem, racism, economics, family conflict, heartbreak, supreme artistry, war and peace, and brotherhood. Life, death and def.

Let’s bring it back to the idea that hip hop is identity. RZA’s so-called last name—Diggs—doesn’t have its origins in Africa. Diggs is the name his ancestors inherited via the system of slavery. Back when blacks in America were considered property (notice how yours truly didn’t say “African Americans,” because we weren’t even “African” Americans at this point), Robert didn’t choose “Diggs.” America did the choosing for him. RZA, on the other hand—Robert chose that name. He assigned meaning to that name, he owns that name, and he controls that name in the same way he controls the Wu-Tang name, and the Wu-Tang brand. He can rewrite history with that golden W.

For “colored” Americans—who would become negro Americans, only to eventually become black Americans and/or African Americans—the power to choose was an option that eluded many of us. But hip-hop identity has changed that for some of us (“us” because this scribe came up in a single parent home in the inner-city like most of the Wu, and dealt with racism and a public school system that prepared us for a life of servitude). Hip hop has taken us around the world and connected us with people living elsewhere who identify with hip hop’s rallying cry: hear me, see me, respect me.

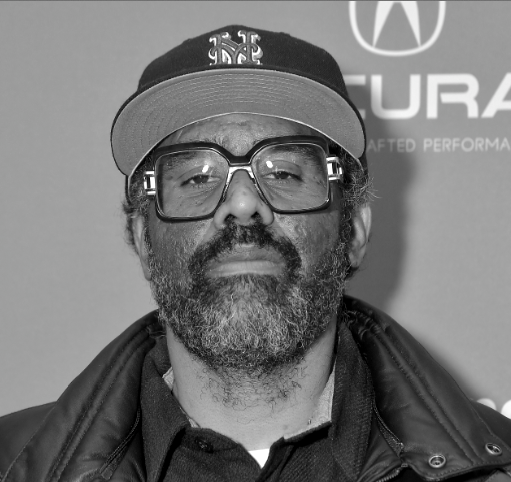

The Wu in Sacha Jenkins' Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men

Sue Kwon/ShowtimeThe Wu’s rise is an inspiration. Their survival is a miracle: 10 guys defying the odds. U-God’s son was shot at age 2. The world counted him out but he scrapped his way back to health. That fighting spirit is in his Wu DNA. That yellow W with the razor edges doesn’t just represent a rap group; it represents the idea of culture and identity, and everything that goes along with it. That flag is recognized everywhere on our once-green planet. It is a rallying cry for freedom, justice, equality and individuality. It is a universal flag that we here gathered today salute.

Twenty-five years ago, hip hop was obsessed with being polished. Producers wanted their beats to sound big and poppy. Some rappers wore shiny suits. The Wu-Tang Clan said fuck that. When Kurt Cobain sang “come as you are, as you were”—the Wu did just that. And like Cobain, who killed hair metal and spandex with his flannels, holey jeans and sludge-pop power chords, the Wu came off the streets, hungry, donning weed-soaked hoodies, armed with blazing bars.

Wu-Tang said, I don’t care how everybody else—or at least black folks in hip hop—is so self-conscious about appearances. And therein lies the essence of Wu-Tang: freedom, and the confidence that goes along with it. RZA refused to take shots from a world that was accustomed swallowing black men like him whole. He had no social capital but recognized how rich he and his friends were when it came to cultural capital. And so RZA and his crew came together to build a business around the talent, around the superheroes of rap. Marvel’s universe is cool, but Wu Tang Clan ain’t nothing to fuck with. Or bluff with.