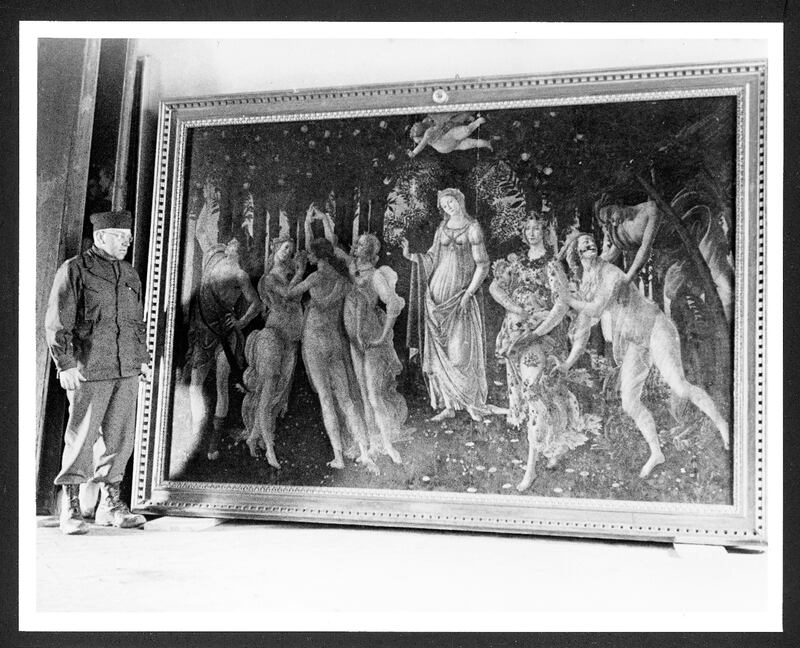

Italy has long been identified by its cultural treasures; Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper is but one. Its ancient cities—Rome, Syracuse, and Pompeii; jewel-box towns—Venice, San Gimignano, and Urbino; places of worship—St. Peter’s Basilica, Florence’s Duomo (Santa Maria del Fiore), and Padua’s Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel; and iconic monuments—the Colosseum, Leaning Tower, and Ponte Vecchio, have been so studied and admired through literature, verse, and image that they have become the shared heritage of all mankind.

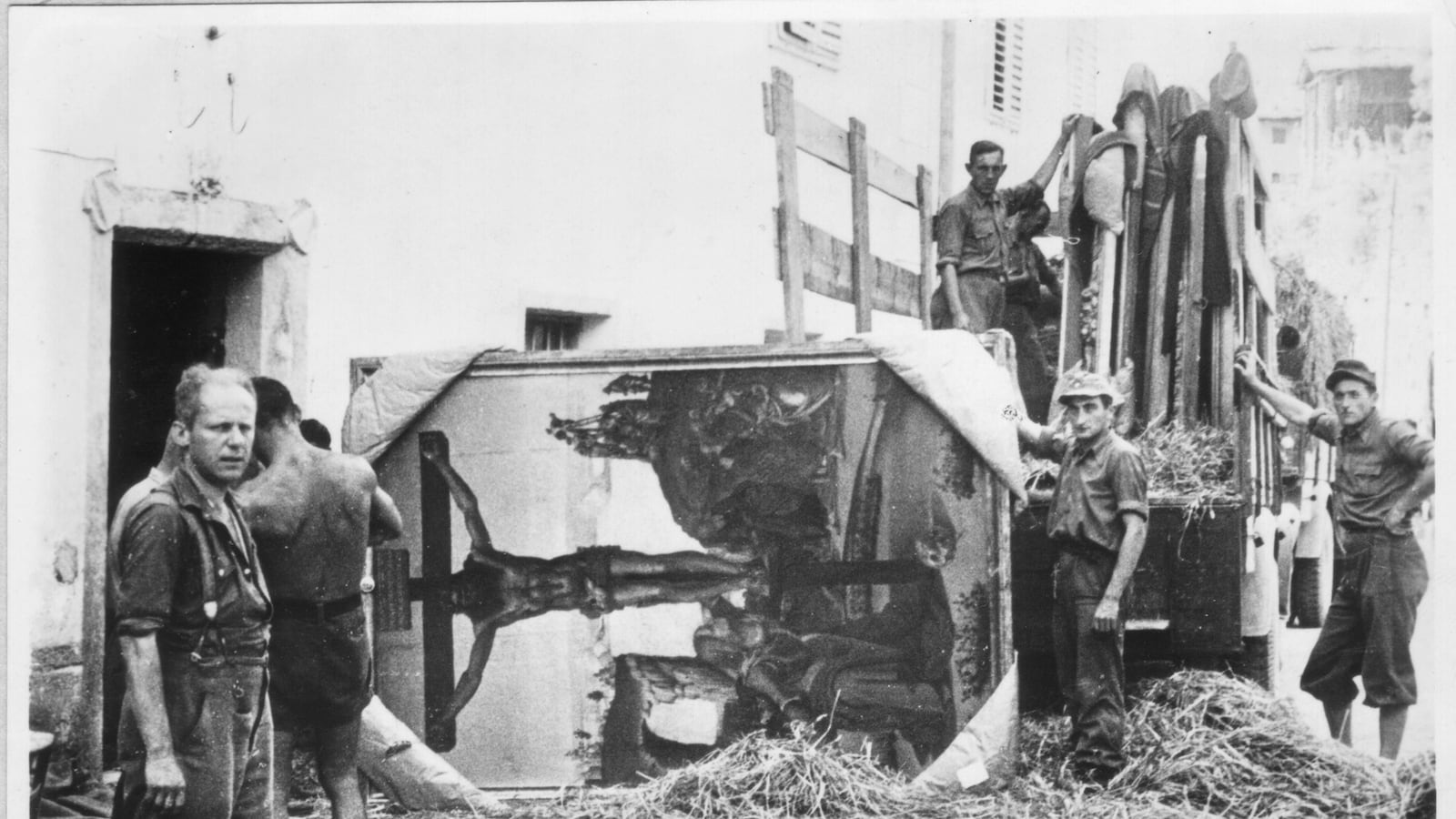

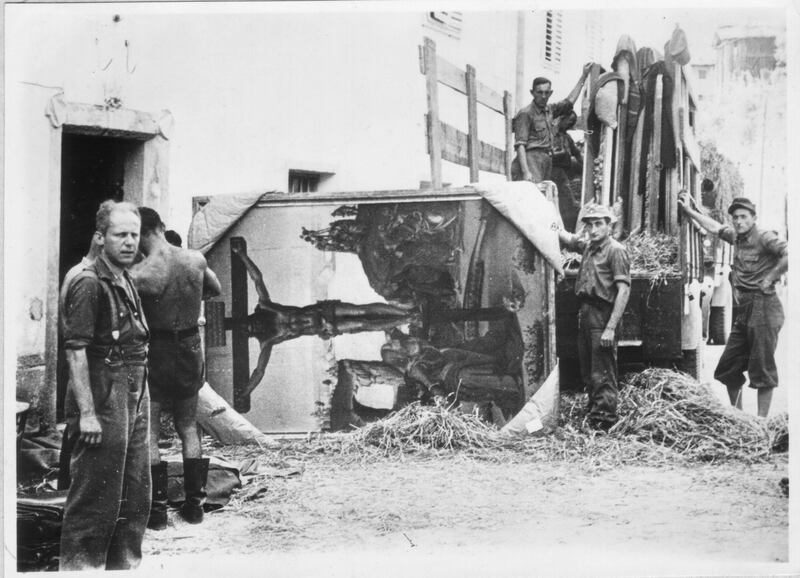

As events in Milan demonstrated, World War II and the new technology of aerial bombardment—in particular, incendiary weapons—posed history’s most lethal threat to that heritage. When the Allies landed in Sicily on the night of July 9–10, 1943, another threat emerged: ground warfare. The Germans were determined to concede not an inch of Italian soil. How many more monuments, churches, libraries, and immovable works of art lay in the path of war? Even then, as the bombing of The Last Supper illustrated, the Western Allies were not immune from mistakes in judgment and execution.

War is many things, but above all, it is messy. Rarely does it unfold as planned. Prime Minister Winston Churchill once observed: “Never, never, never believe any war will be smooth and easy, or that anyone who embarks on the strange voyage can measure the tides and hurricanes he will encounter.” Ethical dilemmas arise. Loyalties are tested, but loyalties to whom? Country, cause, or self ? The effort to protect Italy’s cultural treasures during war lived up to Churchill’s admonition.

Few wartime voyages provide such a strange and fascinating story. During World War II, the task of saving Italy’s artistic and cultural treasures fell to a diverse and often surprising cast of characters, including army commanders, Italian cultural officials, leaders of the Catholic Church, German diplomats and art historians, Nazi SS officers, OSS operatives, and partisans. Motives ran the gamut. Not everyone behaved as expected—far from it. But there was also a little-known group of American and British men—museum directors, curators, artists, archivists, educators, librarians, and architects—who volunteered to save Europe’s rich patrimony.

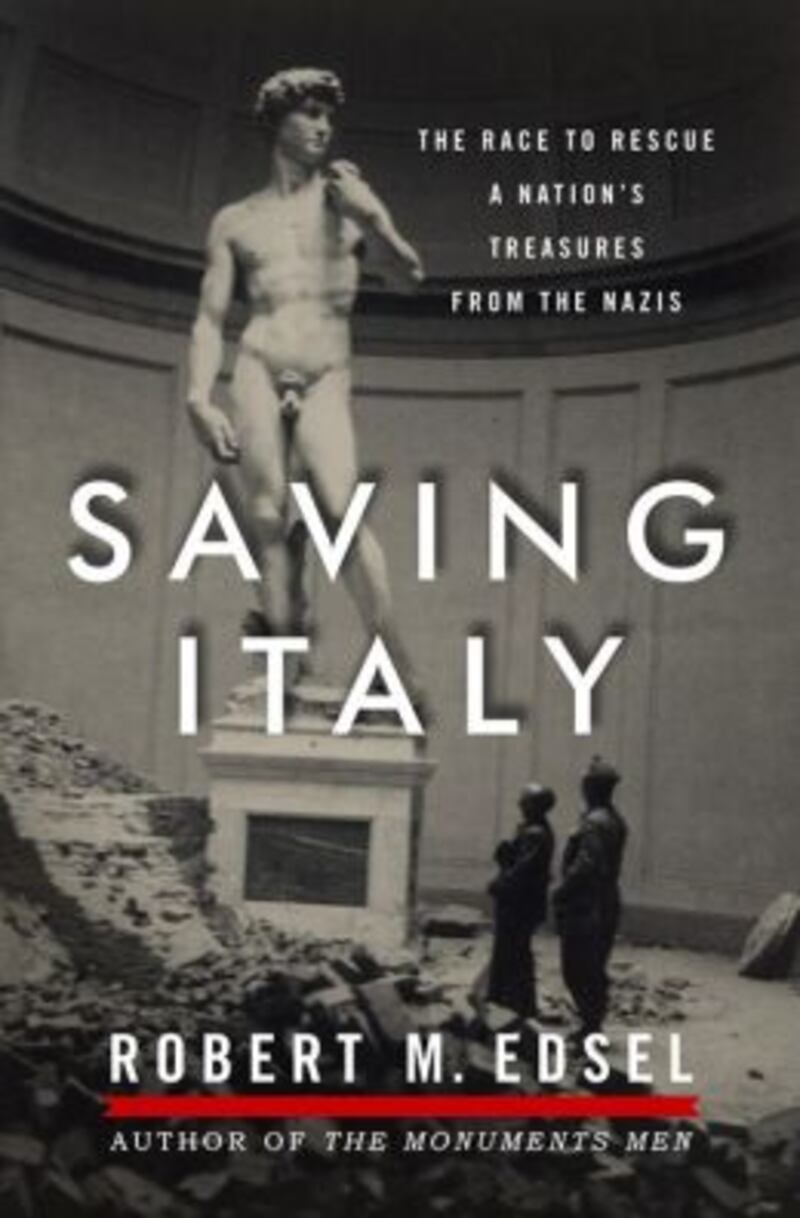

They became known as “Monuments Men.” This middle-aged group of scholar-soldiers faced a seemingly impossible task: minimize damage to Europe’s single greatest concentration of art, architecture, and history from the ravages of a world war; erect repairs when possible; and locate and return stolen works of art to their rightful owners. Their mission constituted an experiment dreamed up by men who at the time occupied offices far away from war. Nothing like this had ever been tried on such a large scale.

At the core of the group were two men whose destinies became intertwined not just with the fate of a nation but also with the survival of civilization’s cultural heritage. Deane Keller, a patriotic 42-year-old artist and teacher with a wife and 3-year-old son, seemed to be everywhere and nowhere, constantly on the move from town to town. Fred Hartt, an impetuous but brilliantly gifted 29-year-old art historian, became so deeply entrenched in the cultural heartbeat of Florence that saving the city’s art became his personal quest, the mission of a lifetime. Thrust together by the democracy of military service, they struggled to survive war, its destructiveness, and, at times, each other.

Robert M. Edsel is the author of the books The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History and Saving Italy: The Race to Rescue a Nation's Treasures from the Nazis.