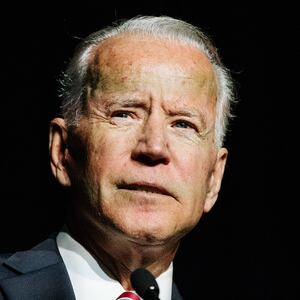

Joe Biden may have thought that patching things up with Anita Hill was the best way to jump-start his presidential campaign. But to many women—including Hill herself—the former vice president’s phone call 28 years after the fact only rubbed salt in the wound.

“The only person I will allow to say that he's done enough is Anita Hill herself,” said women’s rights activist Andrea Pino, who previously worked with Biden on campus anti-rape efforts. “And if Anita Hill is saying that he has not properly apologized, then I will go with what she said.”

Biden’s campaign says he called Hill weeks ago to address lingering tension around the 1991 confirmation hearings in which Hill accused then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment. Many now fault Biden, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time, for failing to give her allegations a fair hearing. Biden himself has expressed remorse for what she endured while testifying.

But in an interview with The New York Times published Thursday—the day of Biden’s 2020 campaign kickoff—Hill said his recent phone call did not constitute an apology. “I cannot be satisfied by simply saying, ‘I’m sorry for what happened to you,” she said. “I will be satisfied when I know there is real change and real accountability and real purpose.”

To many women, the decades-delayed call felt disingenuous—a thinly veiled attempt to win back female voters energized by the #MeToo movement and Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearings. If that was the intent, however, it seems to have backfired.

“[Biden] is primarily focused on what he believes acknowledgement looks like and what he thinks it means to take responsibility, instead of centering the needs and the requests of the people that he's harmed,” said Shaunna Thomas, co-founder of women’s rights group UltraViolet.

“The experience we've had of him is sort of taking half responsibility and half measures,” she added. “It seems he's kind of taking that road again, and I think women are going to continue to be frustrated by the way he's showing up.”

Thomas also acknowledged, however, that she wasn’t sure how the controversy would affect him in the polls. Biden’s presidential ambitions have already been rocked by allegations that he touched women in ways that made them feel uncomfortable—allegations he later appeared to mock at a public event. With the Hill call, Thomas said, “I don’t think he lost any more ground than he could have lost.”

It also wasn’t the first time Biden attempted to make things right with Hill. In 2017, the former vice president told Teen Vogue he wished he could have done more during her hearing, and said he owed her an apology. (He did not call her at the time to deliver it.) Just last month, Biden told an audience of campus anti-rape activists he was sorry he “couldn’t give her the kind of hearing she deserved,” adding, “I wish I could have done something.”

Molly Coleman, an organizer with Harvard Law’s Pipeline Parity Project, said she did not think Biden had taken full responsibility for his role in the hearing. That, coupled with the allegations of inappropriate touching, made her question whether the former vice president was ready to tackle gender inequality more broadly.

“If he wants to be the president of the United States of America, this is something that is going to be confronting him in big and small ways,” she said. “And if in this example—that has been the topic of national conversation for decades—you’re not able to do better, it’s really disappointing.”

Brenda Choresi Carter, the director of the Reflective Democracy Campaign, took a more optimistic view. While she left it to Hill to decide whether Biden’s call was adequate, Carter said the fact that he felt obligated to call at all showed how times have changed. With a record number of women and women of color running for president, she said, candidates like Biden now have to take their issues and experiences seriously—even if they don’t always get it right.

“It really points to the significance of several other women in the presidential race,” she said. “They have a certain kind of life experience that others want to see represented in the halls of power, and it increases the demand on Joe Biden and other candidates to demonstrate some kind of understanding of those life experiences—even if they haven’t lived them.”