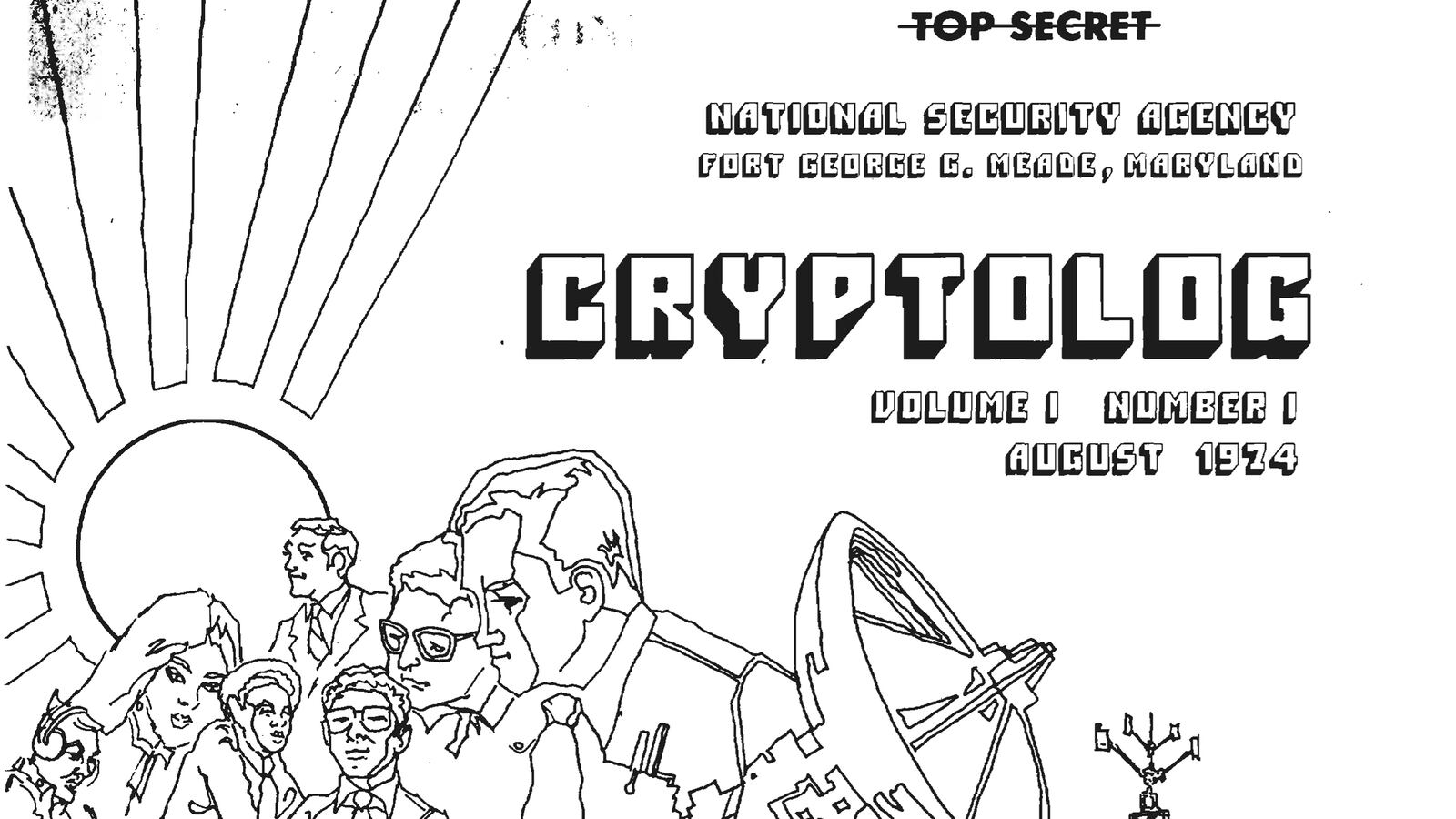

Have you ever wondered about what life is like for a professional U.S. government eavesdropper? Well, you’re in luck. This month the National Security Agency (NSA) declassified 23 years’ worth of issues of “Cryptolog,” the newsletter written by and for the code-breakers, linguists, and computer scientists at the U.S. government’s most secretive intelligence organization. The issues span from 1974 to 1997.

One article, from 1997, predicted a coming “cyber war,” complete with “worms, logic bombs, trojan horses” that could be “extremely destructive.” Other pieces introduced NSA employees to the inside workings of the agency’s own television network. Other newsletters include pieces on a wide range of topics, from how to learn language through hypnosis to an exploration of how the Soviet Union encodes military communications.

While the NSA has released material in the past and even a few, less-sensitive, in-house newsletters, the declassification of Cryptolog is significant because the NSA rarely talks about what it does. Its mission—to monitor the electronic communications of foreign governments, militaries, and other entities—is one of the country’s most sensitive.

“This is a substantive release of material related to NSA's core mission,” said Steven Aftergood, the head of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists. “It goes well beyond the usual administrative trivia of the monthly NSA Newsletter, and gets into the nuts and bolts of cryptography, albeit with a fair number of redactions.” Cryptography is the art of coding and decoding information between parties.

In the past, the NSA has released historical studies on incidents like the downing of the USS Liberty, a Navy spy ship mistakenly attacked by Israeli fighter jets during the Six-Day War. But the release of the Cryptolog Newsletters “is the most voluminous and important release of internal NSA records on cryptography that we have seen,” says Aftergood.

The release of the materials was spurred in part by a group of U.S. government employees who run the website Governmentattic.org. One of the employees, who asked that his name not be used, said he requested the NSA conduct what is known as a mandatory declassification review of the Cryptolog newsletters. “In this case, they were cooperative,” he said.

An NSA spokeswoman said the agency is “committed to transparency and openness,” and “recognizes that the sum value of these documents is significant to NSA's history and to public understanding of our functions and activities.”

Many articles in the newsletters are whited out. But they nevertheless provide a window into the culture of the NSA and the highly skilled people who work there. In the August 1974 inaugural issue, Maj. Gen. Herbert Wolff, who was then the deputy director of operations for the NSA, wrote that the newsletter was meant to be an “interchange of ideas in technical subjects in operations.” That issue featured articles on how to write spot intelligence reports, an essay on what it means to be a “collector” of intelligence, and a dispatch from the Seventh World Congress of Translators, held in Nice, France.

As one might expect from a newsletter appealing to code makers and code breakers, the publications feature all matter of puzzles, word jumbles, and the occasional crossword. In 1989, a poem is featured with this opening stanza: “there was a little cipher/all dignified and stuff/who was tricky as the devil/but not secure enough.”

The July 1994 edition of Cryptolog features a long story on the NSA’s own in-house television news network. The “Broadcast Center” began airing the show in 1992 as a kind of news show based on intercepts and other material sometimes called “signal intelligence,” or SIGINT. “A video reporter’s day is probably at least as busy as that of a CNN correspondent,” the article says. “Arriving in the newsroom he or she ‘hits the ground running’ poring over the recent SIGINT products.”

The documents also provide a window into the thinking of top NSA officials at the dawn of the Internet era. In the Spring 1997 newsletter, William Black, who was the special assistant to the NSA director for “information warfare,” wrote a piece that introduced the new concept of cyber warfare.

“There are specific types of weapons associated with Information Warfare,” he writes. “These include viruses, worms, logic bombs, trojan horses, spoofing, masquerading, and ‘back’ or ‘trap’ doors. They are referred to as ‘tools’ or ‘techniques’ even though they may be pieces of software. They are publicly available, very powerful, and, if effectively executed, extremely destructive to any society's information infrastructure.”

In 1997, “information warfare” was a totally new concept. But today it is a core mission for the NSA. In 2010, when President Obama created a Cyber Command, he decided to house it at the NSA and make the first general in charge of it the current NSA director.