The documentary Advocate, directed by Rachel Leah Jones and Philippe Bellaïche, follows the life, work, and activism of Jewish-Israeli lawyer Lea Tsemel, who defends Palestinian clients accused of terrorism. It’s an unsentimental yet greatly moving work of political cinema, patiently making the case for unrelenting radical activism in a war-torn and unjust society.

Tsemel, who proudly wears her media-conferred badges of “leftist” and “devil’s advocate”—calling them “compliments”—has spent over 30 years advancing the Jewish-Israeli anti-Zionist tradition, which has existed since the very beginning of the occupation during the Six-Day War of 1967; her husband is the Marxist and anti-Zionist activist Michel Warschawski, who also became her client after being accused of collaborating with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine in 1987. Tsemel’s activism crucially takes place not only in streets and prisons, but in the Israeli courts where she hopes justice may one day be fairly applied to those exercising their right to resist the occupation. That outcome seems wildly unlikely, but in the film, civil and human rights lawyer Avigdor Feldman admits that, despite his own lack of faith that justice will ever exist for the Palestinian people under Israeli occupation, Lea’s radical optimism puts her at an advantage.

Since the filmmakers were never allowed in the courtroom, Advocate is less of a procedural than it is a portrait of how activism can and must work under extreme obstacles—the film doesn’t condense Tsemel’s court cases into simple narratives of crime and punishment or wins and (overwhelming) losses, but places them, as Tsemel would, in the context of war, empire, and state-sanctioned brutality. Tsemel believes her clients have committed acts of violence or intimidation as forms of self-advocacy and not as acts of hatred or anti-Semitism. She takes the people she defends at their word, keenly listening to the testimonies and confessions (extracted by regulated yet still corrupt Israeli police interrogators) and building cases around the right to respond to losses of freedom, equality, and citizenship. The best possible outcome for these defendants is reduced prison time, not acquittal. Still, both the film’s endurance and its subject’s (Tsemel is nearly 75 and still taking on clients) are lessons for Americans at a time of impending war against Iran and ever-increasing Islamophobia: The fight will be long and hard, and we owe it to those directly suffering to get involved.

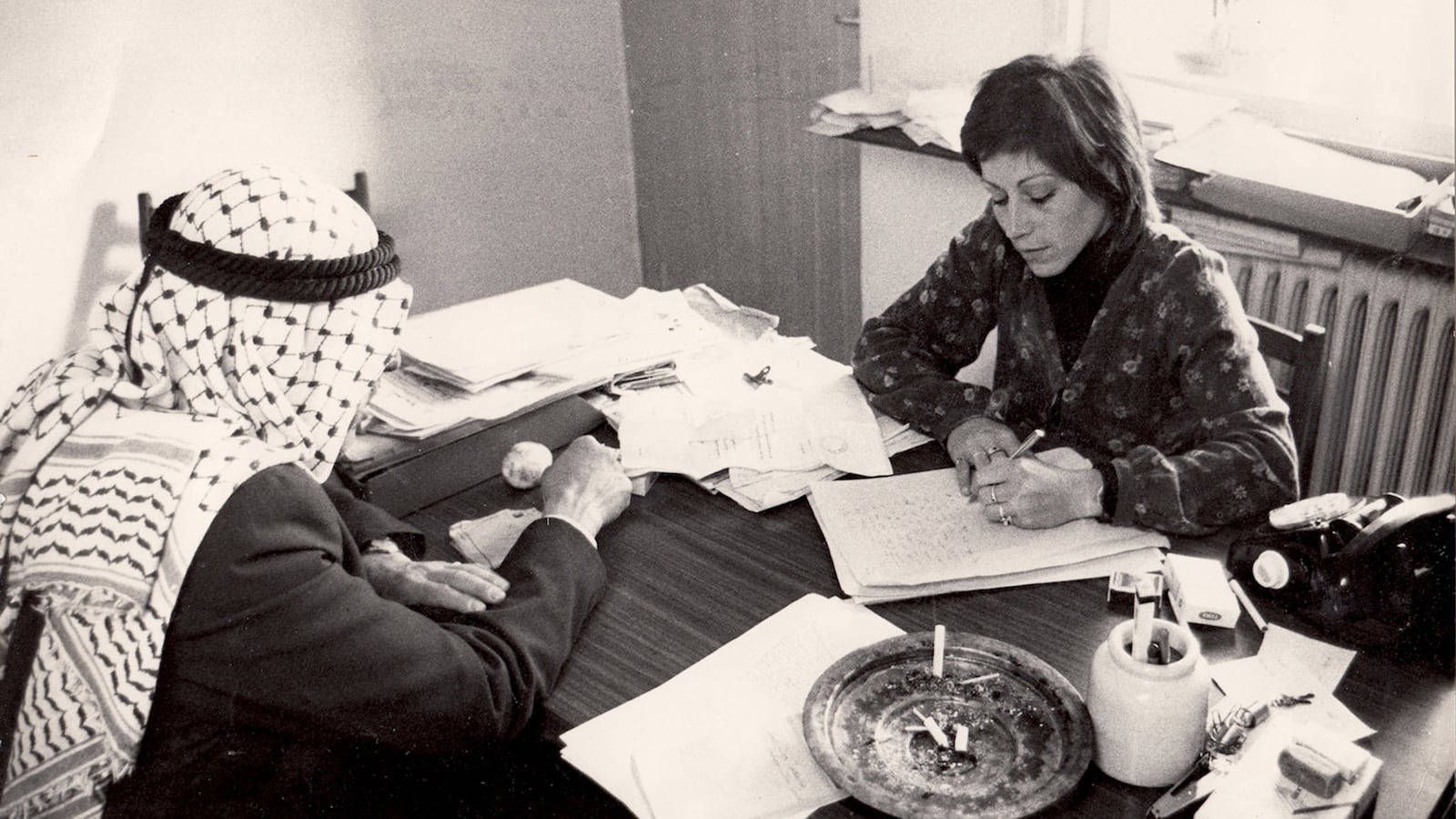

Advocate is not a documentary made to comfortably confirm the beliefs of those most likely to see it; it does not turn away from the accusations of terrorism made against Tsemel’s clients—who in many cases do kill or cause harm—or from the crowds and mobs who, for instance, demand the execution of a Palestinian child who waved a decorative knife in a Jewish neighborhood as a threat and killed no one. This is not a film that uncritically repeats the pronouncements of those in power or buys into the propaganda of war espoused by media outlets and governments. Instead, by depicting both the mundane and extraordinary—including archival footage and photographs, testimony from both Jewish-Israeli and Palestinian activists (as well as Tsemel and Warchawski’s children, Nissan and Talila), and dynamic shots of Tsemel’s everyday lawyering—the film delivers a portrait of radical activism that may be able to disturb and awaken the complacent and barely-critical.

And more importantly, the film can serve to reinvigorate those already invested in protecting their Iranian, Iraqi, and Muslim neighbors, who will surely be on the receiving end of hatred and human rights violations as war in the Middle East rages on.

Issue docs receive their fair share of fatigued responses from those hoping to be delighted and entertained by all cinema, but in championing humanity not abstractly, but under historically-specific and morally-necessary circumstances, Advocate is the most urgent and transfixing film I’ve seen in a long time. For those of us overwhelmed by the ever-expanding demands of modern society—the need to earn money and achieve status so we can not only meet our needs but desires—self-sacrifice, whether that be through career, community activism, or the expenditure of monetary resources, may seem like a nostalgic, idealistic concept. Yet, as a rule, struggle has always been required in the fight for justice. If we’re committed not only to our own personal freedom but the freedom of others, we cannot simply go on with business as usual, competing for the rewards and accolades that are meant to validate and protect us and our various privileges.

During his interrogations in the late 1980s, Warchawski was told by his torturers that if he renounced the Palestinians he could do whatever he wanted with his organization—he just had to pick the side of the Jewish people, for whom there was (supposedly) democracy. Warchawski insisted, “out of self-respect, I won’t say out of courage,” on remaining in “the gray area”—meaning loyal to both the Jewish and Palestinian people. Jones and Bellaïche also give Tsemel and Warchawski’s children, Nissan and Talila, the chance to share their feelings about coming second to their parents’ radical and, in Israel, deeply controversial work: As children, it was tough to accept and difficult to comprehend; as adults, they not only feel proud but protected.

Advocate expresses a truly universal truth for progressive movements: While active struggle requires significant sacrifice and even personal danger, it is in service of a greater, kinder future for all people, both intimate and unknown.