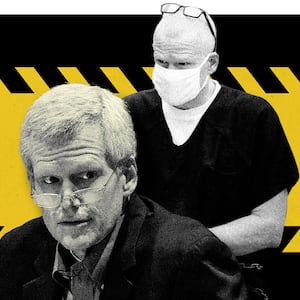

Alex Murdaugh was born to be a lawyer.

For almost a century, members of the Murdaugh family served as solicitors (another name for local prosecutors) in five counties in South Carolina’s Lowcountry before establishing one of the most renowned personal injury law firms in the area. Soon after graduating from the University of South Carolina’s law school in 1994, Murdaugh assumed his role in the legal family dynasty, joining Peters, Murdaugh, Parker, Eltzroth & Detrick (PMPED) alongside his brother and father.

Eventually, Murdaugh began to volunteer part-time in the 14th Circuit solicitor’s office and even served as the president of the state trial lawyers’ association.

But his former law firm colleagues admitted during Murdaugh’s murder trial this week that the 54-year-old might not have been as legally gifted as his family lineage would suggest. In fact, two of them described Murdaugh as a loud and “frenetic” lawyer who kept different hours than everyone else—and was able to keep a “good clientele” roster because he had the “gift of the gab.”

“He was successful not from his work ethic, but his ability to establish relationships and to manipulate people into settlements and clients into liking him,” Jeanne Seckinger, the firm’s chief financial officer, testified on Tuesday. “The art of bullshit, basically.”

Ronnie Crosby, another former law partner who has known Murdaugh for over two decades, simply told the jury that Murdaugh “wasn’t a real student of the law.”

The details about Murdaugh’s allegedly questionable professional proficiency are crucial for the prosecution’s argument that he murdered his 52-year-old wife, Maggie, and his 22-year-old son, Paul, in a desperate attempt to garner sympathy and shift the focus away from his financial crimes.

Murdaugh has pleaded not guilty to two counts of murder and two counts of possession of a weapon during the commission of a violent crime in connection with the case, which has been deemed the “trial of the century” in South Carolina. His lawyers, however, have stressed that there is no concrete evidence—or motive—to prove Murdaugh wanted to harm his “wonderful” family.

Over the last two weeks, jurors have heard graphic testimony about how Paul and Maggie were fatally shot near their hunting estate’s dog kennels on June 7, 2021. But on Tuesday, after a crucial ruling from Judge Clifton Newman, prosecutors were finally able to provide context on why they believe Murdaugh was motivated to kill his family.

Both Seckinger and Crosby went into detail about how the law firm discovered Murdaugh had been funneling millions of dollars away from the clients and company for years. Seckinger even detailed how she confronted Murdaugh about the missing money hours before the murder—and again three months later, when he eventually copped to his crimes and resigned from his post.

Murdaugh’s colleagues also provided a window into his personality and close-knit home and work life. Seckinger, who knew Murdaugh since high school and considered him a friend, said that PMPED was more of a family environment than a workplace.

“These attorneys work as a brotherhood,” she said. “They trusted him”

That trust, Seckinger said, allowed Murdaugh to maintain an eccentric work behavior different from his peers, including constantly being on the phone and always being “loud.. busy... [and in a rush].” It also allowed Murdaugh to keep his job despite not necessarily being the most gifted lawyer, who was sometimes forgetful and “all over the place.”

Crosby seemed to reiterate his colleague’s assessment of Murdaugh, who he said shined as a lawyer because of his personality. He added that among Murdaugh’s legal “quirks” included walking out of depositions and partner meetings to answer the phone.

“He was good with people,” Crosby said. “Very good at reading people. Very good at understanding people. Very good at making people believe he cared about them and building a rapport and trust with them.”

The lawyer also noted that he was extremely close with Murdaugh and his family, noting that his two sons would refer to him as “Uncle Ronnie.” Tearing up, Crosby added that Paul would often take his own son hunting and fishing.

That tight bond, he said, spurred him to immediately jump into his car to Murdaugh’s estate when he learned that Paul and Maggie had been murdered. He added that in the days after the murders, the law firm rallied around Murdaugh and went to the house daily out of concern for his mental state.

Eventually, however, Cosby and Seckinger said Murdaugh was eventually hit with the mounting questions about missing funds—something that he eventually copped to. He resigned from PMPED on Sept. 3, a day before he allegedly staged a botched assisted suicide plot in order for his only surviving son, Buster, to receive his $10 million insurance payout.

Cosby said that the firm was also forced to inform the South Carolina Bar about Murdaugh’s alleged misconduct. Last July, South Carolina Supreme Court disbarred Murdaugh from practicing law in the state after an investigation into allegations he posed a “substantial threat of serious harm to the public or to the administration of justice.”

But those who were once closest to Murdaugh have since admitted in court they may have never really known the former lawyer they worked alongside for years.

“I don’t think I ever really knew him,” Seckinger said. “I don’t think anybody knows him.”