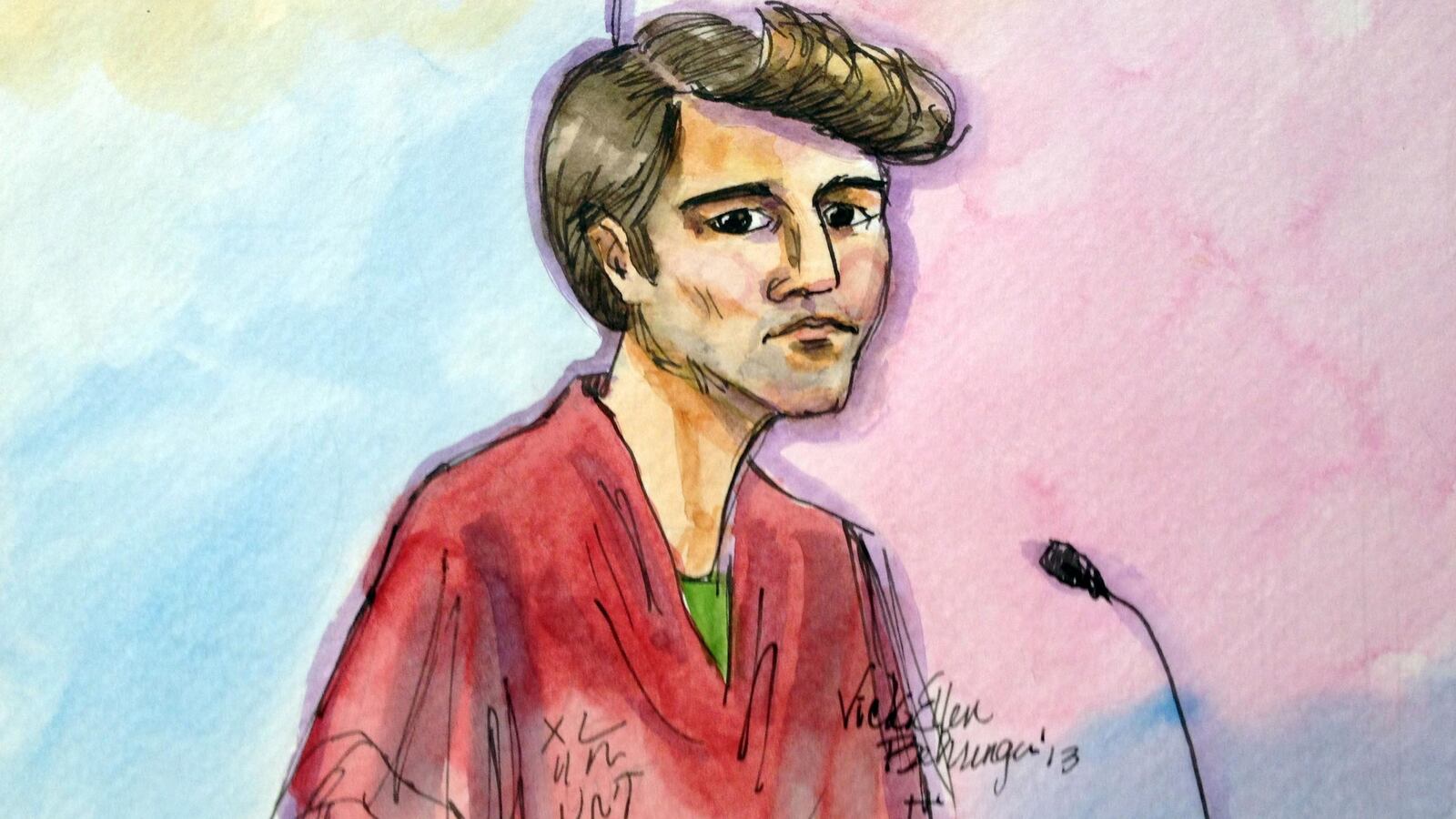

Ross Ulbricht, the 29-year-old alleged mastermind of the underground Internet drug bazaar Silk Road, strode into room 15A of New York Daniel Patrick Moynihan Courthouse on Friday to face charges that could send him to prison for life.

Among them: that he engaged in a narcotics trafficking conspiracy, operated a continuing criminal enterprise, conspired in “computer hacking,” and engaged in money laundering. The charges, Forbes’ Andy Greenberg further explains, include a charge sometimes called the ‘kingpin statute,’” which is “‘often aimed at mafia and cartel bosses.’”

A few rows back sat his family; his mother, father, and sister, sitting solemnly, and staring silently straight ahead, watching the man known to many as Dread Pirate Roberts take his seat before the judge’s bench. His attorneys sat at his sides.

Wearing dark blue prison-issued scrubs over a t-shirt, Ulbricht turned, surveyed the audience, and his eyes landed on his family. He smiled. “Hi,” he mouthed.

The rest of the audience watched on. Unusually for New York—and for the community Ulbricht’s once inhabited—nobody was looking at their smartphones. All electronic devices had been checked with security. For a digital trial, those who will be covering it will have to do so with the analog method of paper and pen.

The judge, United States District Judge Katherine B. Forrest, entered.

“Did he read the charges filed in the indictment against him?” she asked.

“Yes,” Ulbricht responded.

Does he understand them?

“Yes,” the alleged criminal mastermind said.

And how do you plead, the judge asked, listing each of the government’s counts one by one and awaiting Ulbricht’s answer.

To each, the same: “Not guilty.”

Not discussed today: Ulbricht’s alleged involvement in six murder-to-hire plots.

The judge, prosecutor Serrin Turner, and Ross Ulbricht’s lawyer Joshua Dratel then spent fifteen minutes haggling over the trial’s upcoming schedule.

The government says it has 8-10 terabytes of data it has gathered off of the accused’s confiscated servers and laptop, and both sides would need time to sift through the servers and rebuild a temporary website and/or database.

The defense would need 30 days to then determine what, exactly, was on the drives—and if it would result in any further motions filed on behalf of their client, and then months to prepare the case for trial.

A date was set: November 3rd, 2014, for when the trial of United States of America vs. Ross William Ulbricht would commence.

Until then, Ulbricht will remain in federal custody, and will, under supervision, have access to a laptop to walk his lawyers through the pile of drives of data the government plans to use to convict him of the charges.

Until then, all Ulbricht’s family can do is wait.

Asked by a reporter if they had had a chance to see their son, the mother answered yes, she had.

Asked if she understood much of the case, or if she had any sense of how things were going, she said no.

But “we’re doing the best we can,” she said in response to a reporter.

With a case surely to be driven by its intricacies—the judge called it “luminous” and “complex”—that’s about the best a family of a well-to-do young man from California accused of running a true criminal enterprise can do.

Silk Road, lovingly nicknamed the Ebay of the online drug world was reportedly founded by Ulbricht in February 2011. Named for the trade routes used in the Han Dynasty, the black market site first gained attention in June 2011 when Gawker published an article featuring the digital black market with the headline “The Underground Website Where You Can Buy Any Drug Imaginable.” It wasn’t an exaggeration. From MDMA to LSD, computer equipment to jewelry, Silk Road dangled a menu listing all the greatest things Bitcoin can buy. The Internet took the bait. By 2011, the site was bringing in $1.2 million a month in revenue, according to a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University. By 2013, the site had over 10,000 listings for drugs.

It’s a website that, the authorities allege in their indictment, “was used by several thousand drug dealers and other unlawful vendors to distribute hundreds of kilograms of illegal drugs and other illicit goods and services to well over a hundred thousand buyers worldwide, and to launder hundreds of millions of dollars deriving from these unlawful transactions.”

The secret to Silk Road’s success was the protection of his customers’ identities through a network known as “Tor.” Initially intended for the U.S. Naval Research Lab, Tor routes traffic through randomly selected relays, obscuring the real location and identity of the user. Using this software, Ulbricht—if he was in fact Dread Pirate Roberts, which he denies—preserved the anonymity of what was likely hundreds of thousands of users.

In a rare interview with The Daily Beast in September, the founder of Silk Road, then known only as Dread Pirate Roberts, explained the impetus behind his virtual drug store:

“People die from ecstasy because of overdose and low purity. These people don’t know what they are taking and how much, but it’s the best they can do because of all the damage prohibition has done to the market for drugs. Silk Road is repairing that damage.”

It was Senator Chuck Schumer who then put pressure on the government to crack down on Silk Road, telling reporters, “It’s more brazen than anything else by light years.” Following an extensive dual investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Drug Enforcement Administration, Ulbricht was arrested on October 2, 2013. At the time of his seizure, the FBI confiscated roughly 26K Bitcoins from the accounts on Silk Road, the equivalent of $3.6 million.