Schools need to be a whole lot more honest with America’s students. If we don’t teach students about the past, we aren’t equipping them with the tools to succeed in the future. And any history of America is woefully incomplete without a thoughtful examination of post-Civil War Reconstruction.

Concerningly, an Illinois middle school teacher stated (in a report that looks at education standards for American history), that Reconstruction is “generally the most skipped and summarized” unit in the history curriculum.

Theron Wilkerson, a Mississippi social studies teacher quoted in this same report went further, saying: “Because teachers are often pressured to ‘teach to the test,’ fruitful discussions about Black political, cultural, and economic autonomy, the potential of radical democratic participation, and the destruction of Reconstruction is lost.”

The aforementioned report, released earlier this year by the Zinn Education Project, showed that primary and secondary curriculum standards on teaching Reconstruction were inadequate in all 50 states. This is a serious problem.

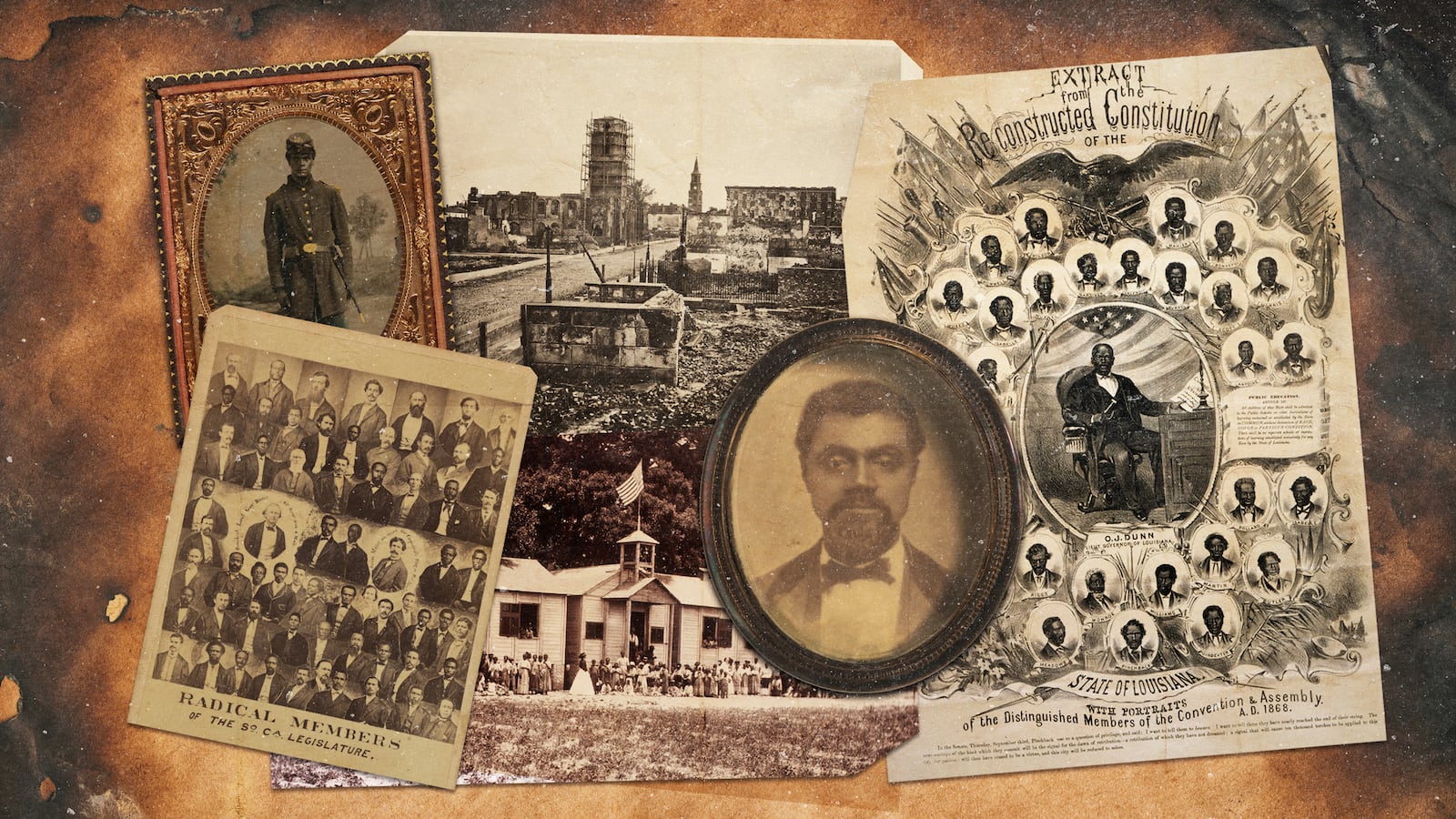

Reconstruction started after the Civil War and lasted from 1865-1877. The United States needed to rebuild and reintegrate formerly seceded southern states back into the Union, while at the same time deciding the legal status of formerly enslaved Black Americans.

In an act of bravery against then-President Andrew Johnson’s wishes, members of Congress—led by representatives who were considered the radicals of their time—passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866. It was the first significant piece of legislation in U.S. history to become law over a president’s veto. Next, Congress enacted the Fourteenth Amendment, which solidified the idea of birthright citizenship and expanded rights to millions of Black Americans.

Nonetheless, this political revolution led to increasingly violent opposition from white Southerners. As the first southern Black politicians reached political office and states funded public schools through newly formed social programs, anti-Reconstruction, white supremacist groups—including the Ku Klux Klan—assembled. They began to spread the myth that Reconstruction was ultimately a plan for black supremacy, and throughout the south they used terror to instill fear in the hearts of Black communities.

Then, during the disputed presidential election of 1876, the Republican candidate, Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes, was forced to broker a deal with anti-reconstruction southerners to remove all federal troops in the South. Hayes got the presidency in return.

This left enforcement of Reconstruction policies up to state and local governments, opening the door for Jim Crow-era segregation laws that remained on the books for nearly another 100 years. Reconstruction, the American project to reunite our democracy, was ultimately left unfinished. And the failure of Reconstruction to be fully realized is still relevant to the present day.

Many Americans have long believed in the dangerous theory that when the federal government acts to help minorities, it’s all just part of a covert plan for Black racial supremacy. This racist and violent ideology is still being proliferated by Fox News pundit Tucker Carlson, and was present in the Buffalo shooter’s alleged manifesto.

And if you look back at the attack on the Capitol on Jan. 6—where an insurrectionist waved a confederate battle flag in the U.S. Capitol for the first time in American history—Eric Foner, one of America’s leading history experts observed that it reminded him of “the overthrow of Reconstruction, which was often accompanied, or accomplished, I should say, by violent assaults on elected officials.”

There is some hope, however, in the form of a growing movement that recognizes how important it is for Reconstruction to be taught in schools. Two hundred of our nation’s leading history scholars wrote a letter to American school districts, teachers, and parents asking schools to prioritize its inclusion in the curriculum, arguing: “Reconstruction is full of stories that can help us see the possibility of a future defined by racial equity. However, too often the story of this grand experiment in interracial democracy is skipped or rushed through in curricula and classrooms.”

The Biden administration is taking steps to address this problem. The American History and Civics grant programs provided through the Department of Education, are affording states with the opportunity to finance history programs that “incorporate racially, ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse perspectives into teaching and learning.” This directive would encourage teachers like Theron Wilkerson—who couldn’t teach Reconstruction because of strict teaching standards—to do so.

Despite this, there is no one size fits all solution, since it’s not within the Department of Education’s jurisdiction to implement nationwide curriculum—it’s up to states and localities to take advantage of these opportunities.

In addition, lawmakers in at least 42 states have introduced bills targeting the teaching of “controversial topics”—which can be subjectively read as almost anything, the fraught history of American racial injustice would probably qualify as “controversial” to conservatives stoking a panic about “critical race theory.”

Reconstruction is a hard story to tell, but doing so makes young Americans aware of some of the hardest truths of the American experience. No nation is morally blameless, so we shouldn’t pretend to act as if our nation has always been perfect.

And it’s not “anti-American” to grapple with our own history.