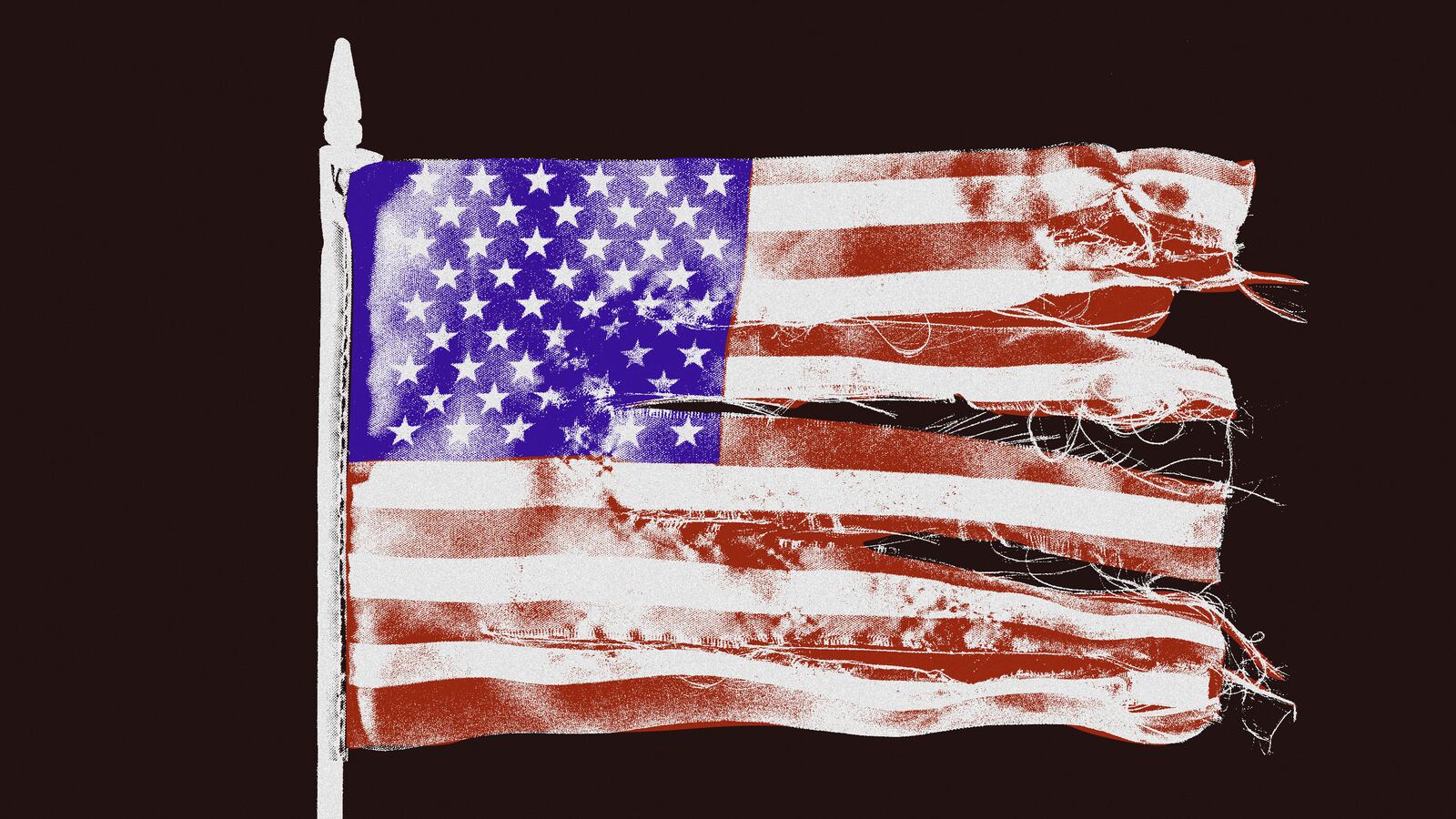

Is America coming apart at the seams? A new Generation Lab poll of rising college sophomores conducted for NBC News confirms that young Americans are segregating themselves along partisan lines.

And as Axios notes, 46 percent of respondents “said they would probably/definitely not room with someone who supported the opposing presidential candidate in 2020 (62 percent of Dems, 28 percent of GOP).”

Meanwhile, 53 percent said they probably or definitely wouldn’t date someone who supported the other team—and 63 percent said they wouldn’t marry someone who supported the other party in 2020.

This partisan division is certainly a departure from America’s past. Yet, this does not appear to be solely a Trump-induced phenomenon.

“In 1960, a mere 5 percent of Republican parents would have objected to [a child marrying someone of a different political party], according to a 2014 Vox article (citing research published in a 2012 paper by Shanto Iyengar, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes), “but by 2010, 49 percent said they’d be displeased.”

Comparing parents’ preferences regarding their children’s spouses with college students’ preferences doesn’t map perfectly, but the trend is clear. What also seems clear is that this trend did not begin with Trump’s 2015 escalator ride announcing his presidential candidacy.

Once again, Trump seems to be as much of a symptom of this trend as he is a cause or accelerant of it.

(Note: A recent Pew Research Center survey shows that “Among Democrats, 63 percent see Republicans as immoral,” which rings true. But according to the data, this number is dramatically “up from just 35 percent who said so in 2016.” When it comes to suggesting that this phenomenon is new, Pew’s polling seems to be an outlier.)

Anecdotal cultural artifacts confirm that a lot of this polarization predates Trump. Think pieces about this subject abounded in 2014 (perhaps not coincidentally, author Greg Lukianoff traces the rise of “cancel culture” on college campuses to 2014, suggesting the ubiquity of social media was a contributor).

Take, for example, this 2014 piece in The Washington Post, which quotes someone named “Ollie” who had this to say on Facebook: “I don’t want to have anything to do with someone who’d vote for Romney… I choose to take their support for Republicans as a personal attack on my right to control my body. Friendship can’t survive that.”

The author, a blogger and former teacher, goes on to say: “Once, I would have pitied anyone who cut off contact with a family member over political differences. That pity came from the privilege of imagining that the stakes were too low to matter. I see now just how high they are.”

Again, it would be understandable if this piece had been written in 2021, after Trump attempted to overturn a free and fair election. What interests me is the convergence of a couple of things.

First, this dogmatic attitude is coming from the left (which flies in the face of the old stereotype about liberals being open-minded free spirits). Second, the political figure who is so outrageous and evil as to warrant cutting off friends and family is… Mitt Romney.

If Republicans felt threatened enough after Romney’s loss in 2012 to embrace Donald Trump in 2016, to what degree did attitudes like this feed a sense of hopelessness that led to radicalization?

To be sure, there are plenty of Republicans who espouse similar separatist attitudes. But according to a 2021 study conducted by the Survey Center on American Life, “Democrats are twice as likely as Republicans are to report having ended a friendship over a political disagreement (20 percent vs. 10 percent).” That is consistent with the latest Generation Lab report. And it comports with a 2014 Pew survey showing that liberals are “more likely than those in other ideological groups to block or ‘defriend’ someone on a social network–as well as to end a personal friendship–because of politics.”

So what are we to make of all of this?

Personally, I can understand not wanting to marry someone who supports a different political party—especially considering how the parties have sorted and are less ideologically diverse. Back in the 1990s (when things were less polarized), I dated liberal women. But I married a conservative. And now that we have kids, I’m especially glad I did. Raising children is hard enough when a couple shares similar values and a worldview. I can’t imagine trying to do so with a house divided (the same would be true, of course, if my wife were some huge MAGA Trump supporter).

My main concern is the absurd notion that you can’t be friends or roommates with people from opposing parties.

For the last dozen years, I have co-hosted a weekly podcast conversation called The DMZ with the liberal columnist Bill Scher. This experience (among others) has forced me to grapple with my own assumptions. It has also taught me that people on the other side of the aisle can be utterly decent and honest.

These friendships that span political affiliations are crucial for a nation’s health and cohesion. And I wonder to what degree these friendships have prevented me from going off the deep end.

It seems to me that cutting oneself off from friends and family who have different views is a way of avoiding having to do introspection. It is also a step towards dehumanizing other Americans, since it’s easy to otherize people you do not know and love. And dehumanization is a step toward violence. These things seem to go hand-in-hand.

However much I wish it weren’t so, it does feel like burgeoning civil war territory—at least culturally and in our personal relationships.