When it comes to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, the earlier you can treat it, the better. Not only can this give patients an opportunity to make crucial lifestyle changes that could delay the disease, but it gives clinicians valuable data that can help guide treatment.

These are hard diseases to catch early, though. Most diagnoses happen when the disease has made itself known through clear symptoms like body tremors or speech changes. By that time, it’s a race to simply treat the symptoms and stop them from getting worse—with precious little time to waste.

However, that might soon all change with some new research published Monday in the journal Neurology that found that signs of Parkinson’s disease can be spotted years before diagnosis and before symptoms begin to show by scanning patients’ eyeballs. The technique utilizes an AI model to detect the presence of the neurodegenerative disease in patients on average seven years before clinical diagnosis.

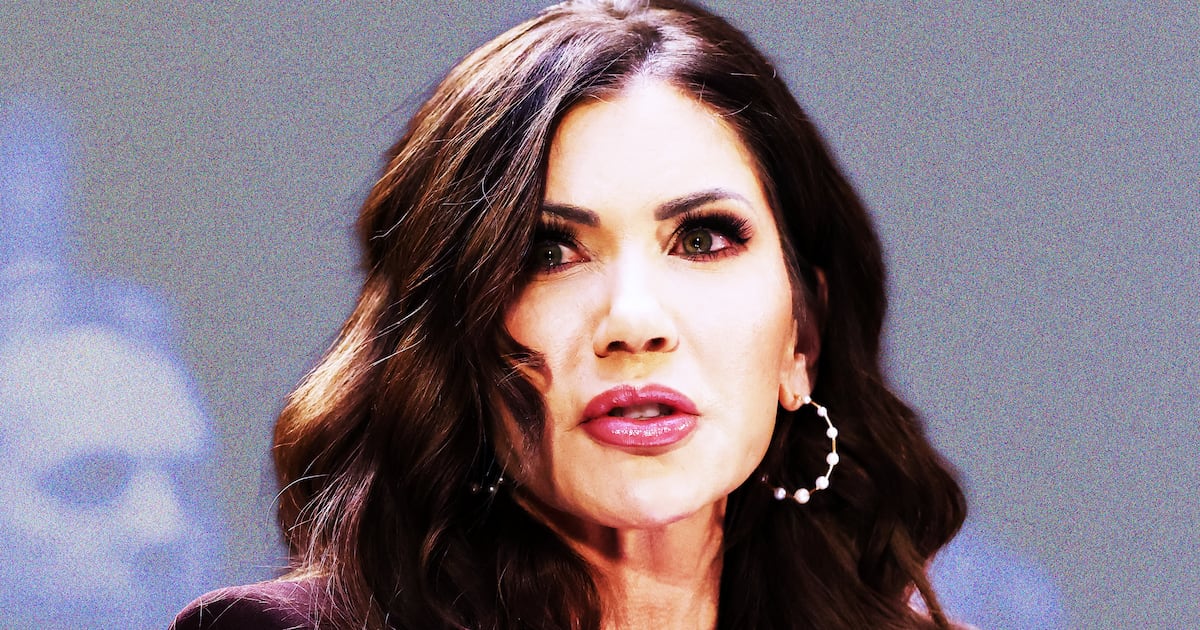

“Finding signs of a number of diseases before symptoms emerge means that, in the future, people could have the time to make lifestyle changes to prevent some conditions arising, and clinicians could delay the onset and impact of life changing neurodegenerative disorders,” lead author Siegfried Wagner, a researcher at the University College London Institute of Ophthalmology, said in a press release.

Scientists have long known that eye scans can reveal a lot about human health including the likelihood of developing cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, high blood pressure, and more. It turns out that neurodegenerative disorders can also be detected through eye scans.

Specifically, the UCL team built off of previous research that they had done on the ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GCIPL), a membrane in the retina. They found that GCIPL atrophy was linked to an increased risk of developing neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s.

The researchers combined these insights with a machine learning model that was trained on AlzEye, a massive dataset of retinal imaging collected to help diagnose different forms of dementia. The AI was also trained using the U.K. Biobank database, which included diagnostic information from healthy volunteers in order to replicate their findings.

Using the datasets, the AI was able to identify very subtle signs of GCIPL atrophy in eye scans and, therefore, their increased likelihood of developing Parkinson’s. These markers were detected up to seven years before diagnosis of the disease.

“This work demonstrates the potential for eye data, harnessed by the technology to pick up signs and changes too subtle for humans to see,” Alistair Denniston, a consultant ophthalmologist at University Hospitals Birmingham who wasn’t involved in the study, said in a press release. “We can now detect very early signs of Parkinson’s, opening up new possibilities for treatment.”

More research is needed to understand why exactly GCIPL becomes thinner as a patient develops Parkinson’s. However, the new detection technique combined with AI is a much needed tool in our fight against a very pernicious and devastating disease.