For Maine Sen. Angus King, who has just returned to Washington after a four-decade absence, the place still holds some terrors.

Not just the “hyperpartisan environment” and dysfunction that convinced his frustrated predecessor, moderate Republican Olympia Snowe, that it was time to leave after eight terms in the House and three in the Senate, but also a scary memory or two.

Scary Memory No. 1: As a young married Senate aide with two small children, King nearly died. After a suspicious mole was discovered on his upper back, he was diagnosed with melanoma, a frequently lethal cancer, and the radical surgery that followed left his right shoulder numb. “Forty years later,” he says, “you could put a needle in my shoulder, and I still couldn’t feel it.” Having survived, he learned “that there were two things that were important: family and friends,” he says. “Everything else you could deal with.”

Scary Memory No. 2: Back in the early 1970s, King was a legislative assistant to Maine Democratic Sen. William Hathaway. One day Hathaway asked for a briefing on a complicated amendment and told King to meet him, a few minutes before the vote, in the historic Senate Reception Room just off the floor. So King studied up on the pros and cons and waited for his boss in the ornately gilded antechamber.

In due course Hathaway ambled in, followed by Maine’s senior senator, Edmund Muskie. “Tell me about the amendment, Angus,” the courtly Hathaway said. Muskie was glowering and towering behind him. At six feet four, with a huge head housing a big brain, he was notorious for his volcanic temper. King continued his briefing.

“Finally Muskie couldn’t stand it anymore, and he physically shoved Hathaway out of the way and got right down in my face,” King tells me. “He said, ‘I don’t give a shit about any of that! I want to know how to vote! And you’d better be right!’ It was the most frightened I’d ever been as an adult. Even today I go in that room and my stomach turns over.”

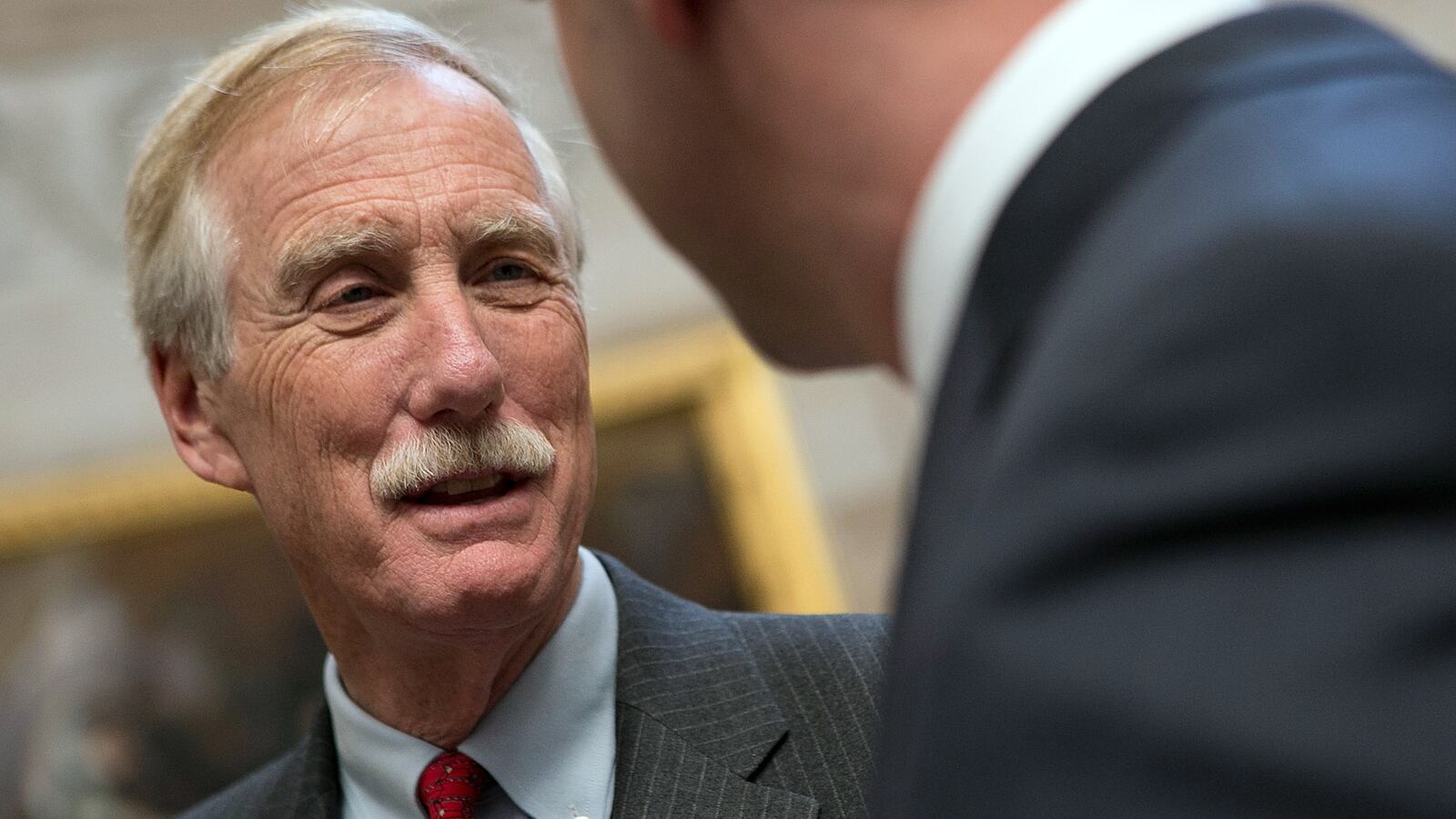

A fit-looking 68-year-old with blond-gray hair and a brush mustache, King is lounging on a shabby sofa on the first floor of the Russell building, in one of the temporary offices assigned to freshmen awaiting permanent digs.

Maine’s newest senator ran as an independent to win with 53 percent of the vote against two major-party opponents. Yet he’s caucusing with the Democratic majority (consistent with his social progressivism and desire for plum committee assignments that he wouldn’t have received as a loner: Armed Services, Intelligence, Budget, and Rules). King hopes his lack of party identification will allow him to transcend petty politics and improve his chances of operating as a “bridge senator” who can work across and between the aisles.

“We’ve got all these problems—fiscal problems, health care, energy, immigration—but the system itself that’s set up to solve these problems wasn’t working,” King says, explaining his reasons for reentering the game after winning two terms in the 1990s as Maine’s popular governor, also as an independent, and then leaving it all behind for private life. “That’s what led me to say we’re gonna do this. It’s uncharted territory, but maybe somebody who’s not affiliated with either of the parties, but who’s also had political experience, can nudge the process toward a little bit better functionality. That’s what we’re trying to do. That’s the motivation.”

King is already in the thick of things. On Thursday he’ll be among the Senate Armed Services Committee members grilling former Nebraska senator Chuck Hagel, President Obama’s controversial nominee for secretary of defense. On Tuesday he met privately with John Brennan, Obama’s nominee to run the CIA. King is reserving judgment on both—indeed, on a lot of things. When I ask if he’s concerned that the National Security Agency might be spying on American citizens, King says, “I don’t know enough to answer that question. I will find out”—a shockingly humble answer for a United States senator.

With his wife, Mary Herman, he’s renting the third floor of a row house behind the Supreme Court—a short walk from the office—and has visited with more than 30 of his fellow senators from both parties, including a long chat with Republican leader Mitch McConnell. It’s King’s political MO. As governor of Maine, he hosted two weekly bipartisan breakfasts for members of the state legislature in Augusta: one for the leadership and one for the rank and file. “It wasn’t policy stuff,” King says. “It was, how are you doing? How are your kids doing? What’s going on in the district? Because a system like ours has to be based on relationships.”

In the service of building relationships that can result in compromise, King plans to replicate this strategic schmoozing in Washington. He argues, for instance, that the five-day Senate workweek of the last century, instead of the Tuesday-through-Thursday schedule that prevails today, would give senators of opposing parties and ideologies more of an opportunity to get to know one another. It would, of course, be a miracle if the leadership ever agreed to such a change, the relentless rhythms of the permanent campaign being what they are, but King lives in hope.

“Angus has got a tremendous reputation for working across the aisle and getting things done. He’s looking at the issues, not the politics. He’s going to be a real problem solver,” predicts West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, a centrist Democrat and ex-governor who is co-chairman of No Labels, a grassroots organization formed to encourage bipartisan cooperation. King, for his part, is fond of quoting such Manchin maxims as “It’s hard to say no to a friend” and there is no such thing as “guilt by conversation.”

Brookings Institution scholar Thomas E. Mann, co-author of It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism, recently had breakfast with King and came away impressed. But Mann points out that Maine’s junior senator “is a man who has led his state and taken positions that put him much more closely within the party he is caucusing with” than with Senate Republicans. King’s best shot at cross-party bridge building, Mann says, is with “those Republicans who are very aware that they gambled and lost on their strategy of demonizing and defeating Obama and now need to broaden their appeal and to become more pragmatic.” (So King should probably not waste a lot of time with Ted Cruz of Texas.)

During his Senate race, King vowed to fight for sweeping reforms in the filibuster rights that contribute mightily to Washington gridlock, and he plans to work on the Rules Committee for election reform as well. But his first roll-call votes last week offered a bleak reality check: instead of requiring filibustering senators to show up and speak on the floor à la James Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, one of King’s favorite movies, the marginal tinkering by McConnell and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid is expected to accomplish little to grease the skids. Filibusters by the Senate minority to block legislation and nominations will continue in most cases almost as before. King stifled his disappointment, saying: “To me, almost as important as the rule change itself was the way we got here—through senators of both parties listening to each other and negotiating in good faith.”

Maine is a tiny state whose population is less than a sixth that of New York City. “It’s a big small town where everybody knows everybody,” King says. “If you stop for gas on the New Jersey Turnpike and see a Maine license plate, you say, ‘Do you know Joe Jabber?’ The answer is, ‘Oh yeah, he’s my cousin.’” Unlike in many other states, where politics can be a blood sport, Maine’s elected officials tend to be civil if not genteel in their disputes. Even King’s Republican Senate opponent, former Maine secretary of state Charlie Summers, declines to say anything bad about him.

Former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell, who most recently served as President Obama’s Middle East envoy, used to appear on Maine Watch, the weekly public-affairs television show King hosted for 17 years, interviewing politicians and moderating debates when he was not toiling in his law office. “I’ve known Angus for a very long time, and he’s able, he’s intelligent, he’s experienced, he’s independent, and I think he’ll do well in the Senate,” Mitchell says. “He knows how to handle himself—he doesn’t need advice from me.”

King had lobbied the state legislature on energy issues and made a multimillion-dollar fortune in the energy-conservation business before launching his successful gubernatorial campaign in 1994. It was his first try at public office, but his celebrity status lent him enviable name ID. King won reelection in 1998 by a 40-point margin. “Nothing like being governor during the longest peacetime expansion of the U.S. economy in history,” King notes.

Then, in January 2003, he gave it all up. He and Mary, his second wife, took their two adopted children, Ben and Molly, out of school and piled into a 40-foot-long Newmar Dutch Star RV to spend nearly six months circumnavigating the country. King’s 2011 book about the adventure, illustrated with pretty vistas and power-wall pics of himself and VIPs, is titled Governor’s Travels: How I Left Politics, Learned to Back Up a Bus, and Found America. The emphasis was on King’s farewell to the game. He spent the next nine years practicing law, running a wind-energy business, and lecturing on leadership at Maine’s Bowdoin and Bates colleges.

Early last year, with the two adult children from his first marriage well established in the world and the younger kids finishing high school and college, Angus and Mary were planning a second RV excursion. Then Snowe made her unexpected retirement announcement.

“I could tell you with total candor that I never contemplated running for the Senate,” King insists. “I never contemplated running for anything.” He’d resisted periodic entreaties to run against Snowe or her fellow Republican Susan Collins, now Maine’s senior senator, arguing that “we have two really good senators, and the only reason for me to run against them would be ego.”

But seats in the Senate don’t come open every day. It’s still a pretty good job, King reasoned, even if Washington is broken. He long ago changed his Democratic Party registration and styled himself as a pro-business fiscal hawk with tolerant social views (though, unlike Snowe and Collins, he eagerly supported Obamacare). King concluded he was uniquely positioned to have a positive impact on the sausage-making. Reacting to Snowe’s grim diagnosis, “I thought, maybe this means we need to try something different, and then I thought, oh, my God! That’s me!” he says. “If I didn’t do it, there was nobody who was going to do it. I was really worried about where we are as a country.”

If King sometimes seems a little amazed at where he finds himself today, he is the only one. “Actually, I wasn’t surprised when he called to tell me several days after my announcement,” says former senator Snowe. “I thought he would run. My husband [former Maine governor Jock McKernan] and I have had dinner with Angus and Mary on different occasions. They remain friends. And he always retained a strong interest in politics and stayed current with the issues ... And given the fact that he’s an independent, he is committed to trying to change the Senate.”