DALLAS—Shelby Hudson just wanted a test. In early December, Hudson, who is incarcerated in Dallas County Jail, realized she couldn’t smell or taste. She had a headache, too, and her bunkmate told her she felt like Hudson was “burning up.”

Nevertheless, the 36-year-old said a guard denied her request for a COVID-19 test. She asked again three days later, then five days after that. Each time, she claims, her request was denied.

Hudson was furious, but unsurprised.

“You have to make a lot of noise to get anything in here,” she told The Daily Beast. “Tylenol, toilet paper, tampons, whatever. You gotta yell and shout if you want them to listen.”

So when Hudson and a few other women in the 28-person jail “tank” couldn’t get clean clothes for days on end, that’s what they did. The women stripped off their rusty jail uniforms and spent a half-hour chanting, “We want clothes!”

Three days later, they finally got them. Four other women backed up Hudson’s claims, and the jail, while denying a protest ever took place and maintaining tests are available, chalked the lack of clean laundry up to a “miscommunication” that a spokesman said has since been corrected.

It’s moments like these that make Hudson believe it’ll be months before a vaccine is made available to her—if it ever is.

“It feels like we’re all alone here,” she said. “I don’t think the people in this city really care about us, and I know people in government don’t care about us, either.”

Since the pandemic began, more than 200 people incarcerated in Texas have died from the coronavirus. At least nine of those people were already approved for parole, and 80 percent of those people were not convicted of a crime.

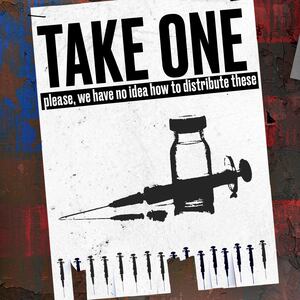

With their fluid populations, jails have become particularly rancid incubators for the virus in Texas and nationwide. But now that vaccines are available, guards and inmates say the state is leaving them out to dry.

“The jail’s response hasn’t changed since March,” one guard at Dallas County Jail told The Daily Beast on the condition of anonymity. “The county only reacts to lawsuits, then goes back to their old ways.”

A spokesman for Sheriff Marian Brown, who oversees the jail, didn’t share any plans for offering vaccines to incarcerated people. Meanwhile, Dallas County Health and Human Services says they do not know when they will be offering vaccines to people locked up in jails, while Parkland Hospital in Dallas said it will be offering a one-dose vaccine to inmates once it is available.

“A one-dose vaccine is necessary,” a spokesman said, “because so many people leave the jail before a second dose can be administered.”

The problem, according to some guards, inmates, and epidemiologists, is that Gov. Greg Abbott has deviated from the CDC’s vaccine rollout recommendations, prioritizing the elderly and people with recurring health conditions over police and teachers. Amidst a confused rollout, epidemiologists say some counties are deviating further still from those guidelines established by Abbott.

Inmates are, unsurprisingly, at or near the back of the line even in states led by Democrats with criminal-justice reform agendas. But in Texas, what a jail guard—or any essential worker, much less an inmate—might receive (and when) depends on where you live.

“Counties are supposed to go with what the state says, but that’s not what’s happening,” Dr. Saritha Bangara, an epidemiologist and public health professor at Austin College, told The Daily Beast. “You can go to one county where teachers are getting them, then drive to another where they can’t. It’s a real mess.”

Spokesmen for Dallas and Tarrant counties said they are following Abbott’s guidelines, but the governor, whose office did not respond to questions for this story, has yet to say when jail inmates will have access to the vaccine.

Meanwhile, even anti-vaxxers locked behind bars are realizing that the shot may be their best chance at any sort of treatment for the coronavirus.

“I would get it if I could,” said Adriana Tijerina, another woman incarcerated at Dallas County Jail who described herself as a skeptic. “It’s better than nothing, which is what we got right now.”

Throughout the country, sheriffs have contributed to the pervasive spread of coronavirus within the jails they oversee. Many have denied masks to their incarcerated people, with one sheriff’s office in Alabama claiming inmates may eat the masks if they were to have them.

Access to masks has been a recurring problem in Texas jails, too. In April, some Dallas detention officers were reportedly told not to wear masks, as they might “spook” the inmates. While that policy has since changed, a guard told The Daily Beast that mask-wearing is not enforced among incarcerated people. That same guard said inmates in Dallas County Jail receive one mask per week, a policy Bangara called “ridiculous.”

Scientists say flimsy mask procedures are just one of the issues contributing to insidious virus spreads inside jail walls.

“It’s impossible to socially distance in jails,” Bangara said. “That’s what worries me about incarcerated populations: there are no mitigation strategies, so those people have no chance. That’s why it makes even more sense to have them high on the vaccine list.”

Epidemiologists canvassed by The Daily Beast agreed that, given the history of spread behind bars, incarcerated people should be high on the vaccine prioritization list. But even they know that's unlikely to happen under Abbott, a notoriously hardline conservative on matters of “law and order.”

“They’re very high risk for transmission, and they have no control over their living circumstances,” said Dr. Rodney Rohde, an epidemiologist and professor of clinical lab science at Texas State University. “Some people may feel like they deserve to be last in line, but I would hope as Texans we can agree that everyone deserves a right to health care. They’re human beings, and we need to be thinking about them just as much as anyone else.”

Rohde was especially worried about people in jails (as opposed to prisons), which he called “vectors of the virus.” Because people are constantly cycling throughout the Texas jail system, he said, it benefits the public at large to prioritize incarcerated people. However, as evidenced by Hudson’s story, some inmates are struggling to get simple necessities.

And a vaccine often seems simply out of reach.

“There’s no plan,” the Dallas County guard told The Daily Beast. “Some of us have started getting it, but we’ve never heard of any kind of larger plan for the vaccine. A lot of guards don’t even want to get it. One of my captains told me, ‘It’s like the Titanic being steered by paddles.’”

Alison Grinter, a Dallas-based attorney, isn’t holding her breath that many of her clients will be able to get the vaccine if and when they want it. Still, she hopes they take it if it ever becomes an option.

“You’re looking at a population that is rightfully so distrustful of the system and the folks who have handled them in the past,” Grinter told The Daily Beast. “Doctors are to Black women what police are to Black men. They’re skeptical of the vaccine, but they’ve only been getting Tylenol and Mucinex for months. So hell yeah, they want the shot. And they need it.”

Grinter also isn’t happy with the state’s fragmented response to vaccine distribution, and several scientists interviewed for this story share her frustrations. The federal government has left distribution in the hands of the states, and Texas has left it in the hands of the counties.

“No one has a clear idea yet of the vaccine rollout plan,” Dr. Rajesh Nandy, an epidemiologist and data expert with the University of North Texas Health Science Center, told The Daily Beast. “Some people know how it’s being distributed in hospitals and labs, but beyond that, there’s a lot of confusion.”

Nandy sits in weekly meetings with hospital administrators and public health officials in North Texas, and he says they have yet to discuss distributing vaccines to jails. The scientist is particularly disheartened by what he sees as Texas politics guiding public health decisions.

“The governor’s administration has at times been reluctant to take on some really strong measures,” he said, “and as a result, no one really knows what’s going on with the vaccine.”

Like Nandy and Rohde, Bangara said incarcerated people deserve fair treatment. She’s not optimistic they will get it.

“Unfortunately, politics drive a whole lot of things, not science,” Bangara said. “People don’t really care too much about science.”