Would you read a book in which the protagonist is a radicalized terrorist?

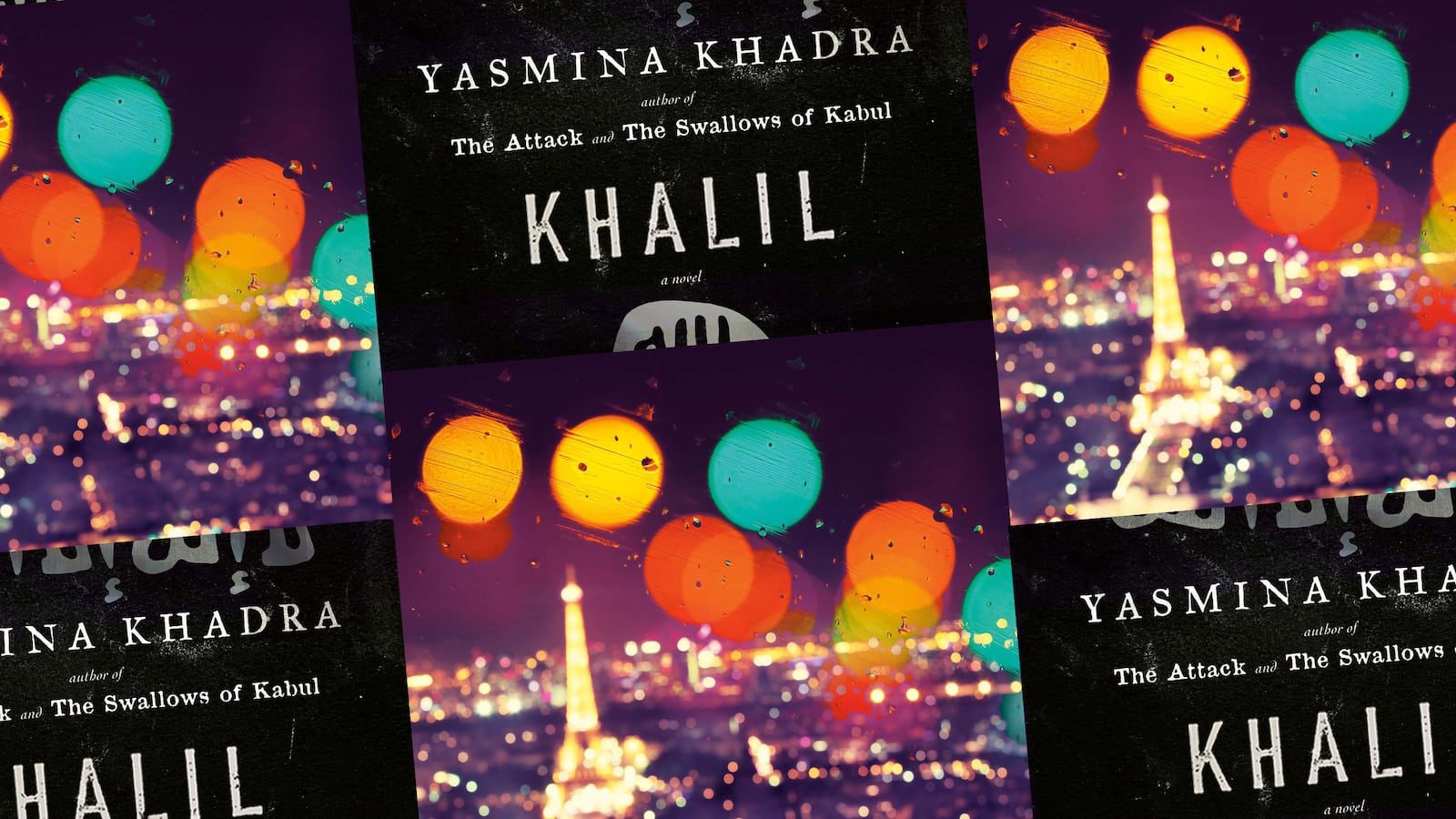

This is the premise of Khalil, a novel by Algerian-born, France-based author Yasmina Khadra. When it was first published in France in 2018, there was a certain reticence towards the book. “Frankly, what interest is there in finding yourself in the mind of one of the perpetrators of the attacks of November 13, 2015 in Paris?” a cultural critic in French newspaper Libération bluntly queried. “Khadra's new novel provokes an impulse to retreat: don't want to read it, don't want to check it out.”

And yet, the reviewer concluded just as firmly: “Such prejudices show that the author was right to write his book.”

The desire to dismiss rather than deconstruct dangerous figures is, in a way, its own danger. Their unfathomable and unconscionable actions shape our anarchic society; avoidance doesn’t eradicate their presence or power. Nor does an engagement with their narrative validate what they do. Confronting our malaise around these figures helps identify how the past has metastasized into the present moment.

Khadra wrote the first part of the novel less than a month after the November 2015 attacks in Paris; he then took more than a year to resume the narrative. He was already well acquainted with the phenomenon of extremism: “I fought fundamentalist terrorism for eight years. In Algeria, the horror was daily,” Khadra recounted, via email, of his military role during the Algerian civil war. (Yasmina Khadra is a pen name he began using in 1990 to avoid military censorship; his given name is Mohammed Moulessehoul.) “I thought I had seen it all, that I was immune to the atrocity, yet each attack that occurs anywhere on earth brings me back to the barbarism that almost took over my country.”

Khalil is narrated by a 23-year-old first-generation Belgian from a Moroccan family. The reader first encounters him in a car full of men driving from Belgium to Paris, intending to blow up the Stade de France while a soccer match is in progress. Khalil—accompanied by Driss, his childhood friend and also-radicalized compatriot—is dispatched to set off a bomb on the RER, the train connecting central Paris to the banlieue. It is Khalil’s first time setting foot in the French capital.

“Khalil is not the ‘hero.’ He is the main character,” the author said. “It's not the same thing. The use of the first person is a pedagogical choice. I wanted the terrorist to confide fully in the reader, without an intermediary. The immediate proximity makes it more explicit. It is a total immersion in the absurd world of murderous ideologies.”

When his explosive vest does not go off, Khalil flees the chaos that ensues. He is not relieved to be alive—he is furious he didn't get to carry out his radicalized apotheosis. Unsure of what to do next, he slinks back to Brussels, avoiding people he knows in Molenbeek, the disenfranchised neighborhood he grew up in and which qualifies as a “mass of misfortune and submission.” He skulks around kebab shops, in public parks, imposing himself at his older sister’s apartment, lying his way into a childhood friend’s place, while he frantically seeks an explanation about his failed equipment.

The shock of the attacks in Paris reverberates back to Belgium and changes security measures immediately: bags searched, identity papers checked, ethnic profiling at an all-time high. Yet Khalil is less worried about the authorities than that the members of the Fraternal Solidarity might think he chickened out.

When it turns out his Paris-based cousin died in the attack on Le Bataclan—the concert venue targeted the same night as the Stade de France, an unthinkable massacre—it shakes not one iota of empathy loose. Khalil espouses nihilistically: “When you’ve chosen to sacrifice yourself for a cause, everything that has to do with life loses its importance.” He shrugs: “Whether you die for your convictions or because you were in the wrong place at the wrong time changes nothing… Such are the whims of destiny.”

Khalil encounters people from his past—his older sister, his twin sister, his childhood friend—yet one of the most telling moments in the novel is a conversation Khalil passively overhears between a group of young North Africans, heatedly discussing the Paris attacks and the effects seeping into Brussels. (Their dialogue is, unfortunately, awkwardly translated… the word choices are distractingly out of step with the slang actual young people would use.) They parse the omnipresent cops, the heightened suspicions, the collective feeling of hchouma, or shame, but also the resistance to feeling this, given that there is no link between Muslims and those twisting the religion into fanatical perversions. One man finds it only natural for ethnicities to be singled out; another retorts that extremist ideology should have no bearing on peaceful Muslims, let alone non-practicing ones. Someone pipes up that the violence is a natural progression of cultural exclusion: that Belgians—born and raised—with immigrant roots are unceasingly treated like unwelcome outsiders.

Khalil falls back in with members of the Fraternal Solidarity and is given a new mission. He is enthusiastic to deliver it, until a brush with grief rattles his convictions. Khadra concludes Khalil with—for this incredulous reader—an inauthentic attempt at redemption. Ultimately, where the author succeeds most is in addressing the statelessness many first generations feel, in which neither conformity nor diversity is rewarded. The systemic contempt of these communities erodes any possibility of hope, and this is a form of violence too.