CHICAGO — It has never been like this at Andre Guichard’s gallery before: the media attention, the controversy, the frank and sometimes uncomfortable discussions.

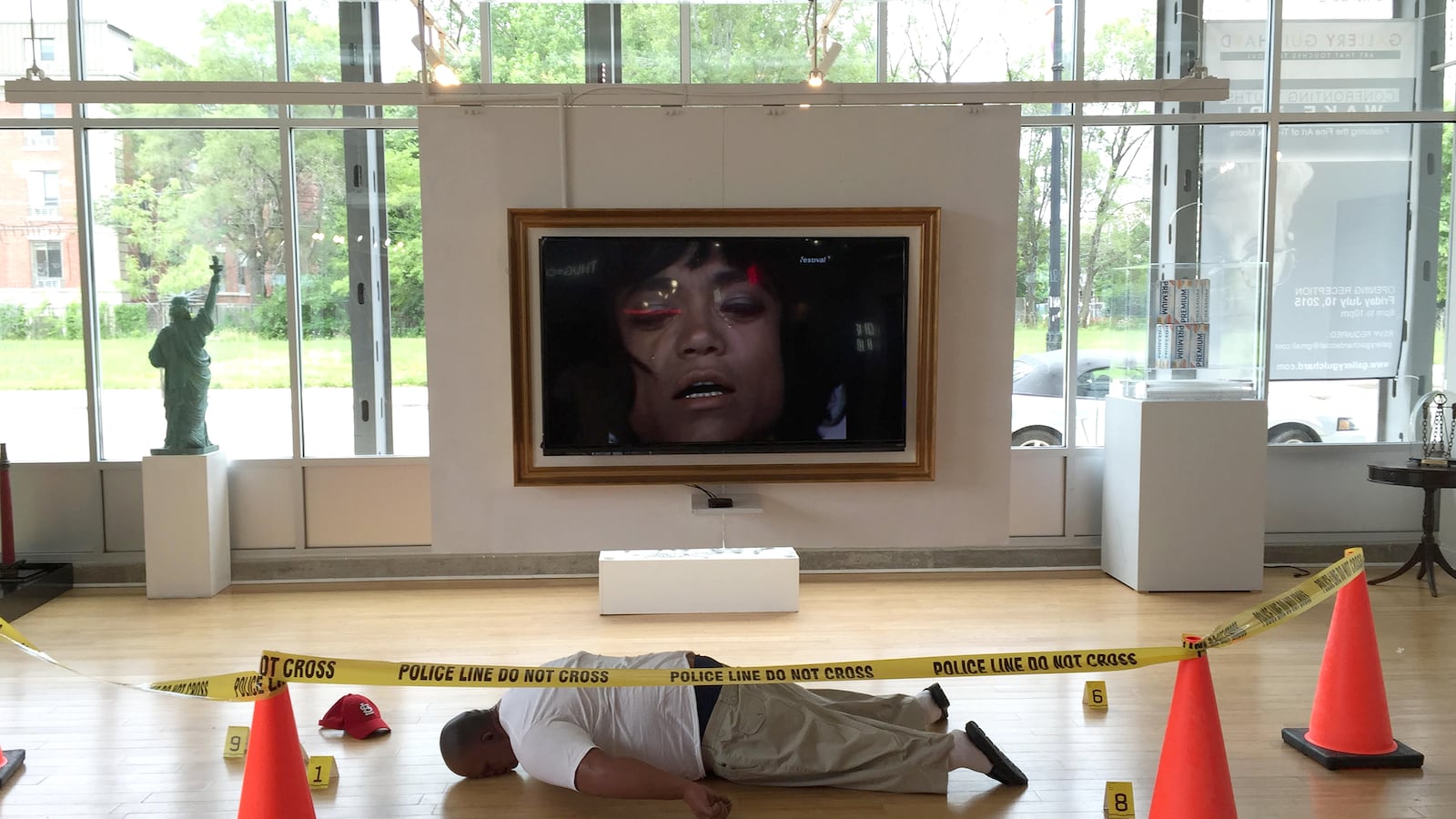

That’s because on the wood floor of the art hall, lying parallel with East 47th Street in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, is a body. There is no blood, as there was on Canfield Drive in Ferguson, Missouri, one day last August, but its identity is unmistakable: This is Mike Brown.

“I’ve become accustomed to having guests read this disclaimer before entering,” Guichard said, pointing to words on a wall just inside the gallery that warn of the shocking display on the other side. “It is jarring.”

You cannot get to Brown’s body, cordoned off with police tape just like it was last summer after Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed the teen. The image of Brown lying face down, hands to his sides while blood drained from a fatal gunshot wound to his head, is unforgettable. Walking around the gallery, one can forget the exhibit depicting Brown’s death is there. Until you catch it out of the corner of your eye, that is, and it gives you a jump.

The scene is painful, humbling, disturbing and thought-provoking, but perhaps not in the way Moore intended. The artist has said the Brown piece, like all others in her exhibit, is meant to prompt a discussion of systemic white privilege and its effects on the black community. So far, however, it has served mostly to trigger questions of whether a white artist should be stepping foot into such sensitive and tender black territory.

Regardless of whether you believe Brown was in the wrong that day, there is no denying that his death has become a symbol. Guichard used the word martyr.

“I don’t mean that in a ‘We’re taking this side over the other’ way. What I mean is that he helped to start a conversation on this,” Guichard said, pointing to the depiction of Brown in his gallery. “I think it helps us to carry on that conversation.”

Guichard and his wife, Frances, are black. The artist who created the mock-up of Brown’s death scene, Ti-Rock Moore, is white. Moore describes the entire exhibit as an exploration of “white privilege through my acute awareness of the unearned advantage my white skin holds.”

On another of Moore’s works is a photo of Brown smiling, the picture that came out after many shared what was criticized as more threatening images of the teen on social media as news of his death exploded. His face is in the middle of an upside-down American flag. On either side are black angel wings. The red stripes of the flag are composed with dozens of copies of the photo that makes Brown’s death scene so instantly recognizable, the one that sparked an online fire that spread quicker than real flames.

Racism, Moore told the Times-Picayune late last year, “makes me want to yell. It’s almost unbearable what’s going on in this country.”

Not surprisingly, Moore’s work has come with quite a bit of controversy and a fair amount of disdain. At least one activist from Ferguson called it “atrocious.” Brown’s own family is apparently split over the art. His mother, Lesley McSpadden, visited the gallery and said she is supportive of the piece. Brown’s father, Michael Brown Sr., told a St. Louis TV station that the exhibit is “disgusting.”

But art is supposed to cause strong reactions, so perhaps none of this is that surprising. What is unsettling about it, said Kirsten West Savali, a senior writer at The Root, is that Moore is “signing her signature on Mike Brown’s dead body.

“She is claiming his dead body as her art. Her art,” West Savali wrote in an email. “The boldness of this, the sheer unmitigated gall, is actually quite stunning.”

Moore’s depiction of Brown, West Savali wrote this week, “revictimizes” the teen.

And it has nothing to do with the artist’s skin color.

“I would still consider the exhibit obscene if a black artist did it, but I have an extremely difficult time believing that a black artist would,” West Savali told The Daily Beast. “There is nothing avant-garde about the exploitation of black bodies. It is not new or experimental or bold. It is an American pastime as old as the country itself.”

There is obvious and stunning irony in the fact that Moore is selling her works, all of them except the depiction of Brown’s death. One, titled “Possession,” shows a black man behind prison bars, upon which are hundreds of real dollar bills. The cost: $5,500. One has already sold.

But for those who consider Brown’s death to have been the beginning of something—a conversation, a movement, a revolution—and who view the teen as a martyr, Moore might be simply doing something that was asked for long ago.

Above the mannequin depicting Brown, plays “Angelitos Negros,” a song re-recorded in 1953 that shares its name with Moore’s work of art below.

“Painter, if you paint with love,” Eartha Kitt sang as tears rolled down her cheeks, “paint me some black angels now.”