Amanda Zikhali was sitting in a small room at the University of the Witwatersrand’s Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Wits RHI) in Johannesburg, South Africa, in February. She was nervous.

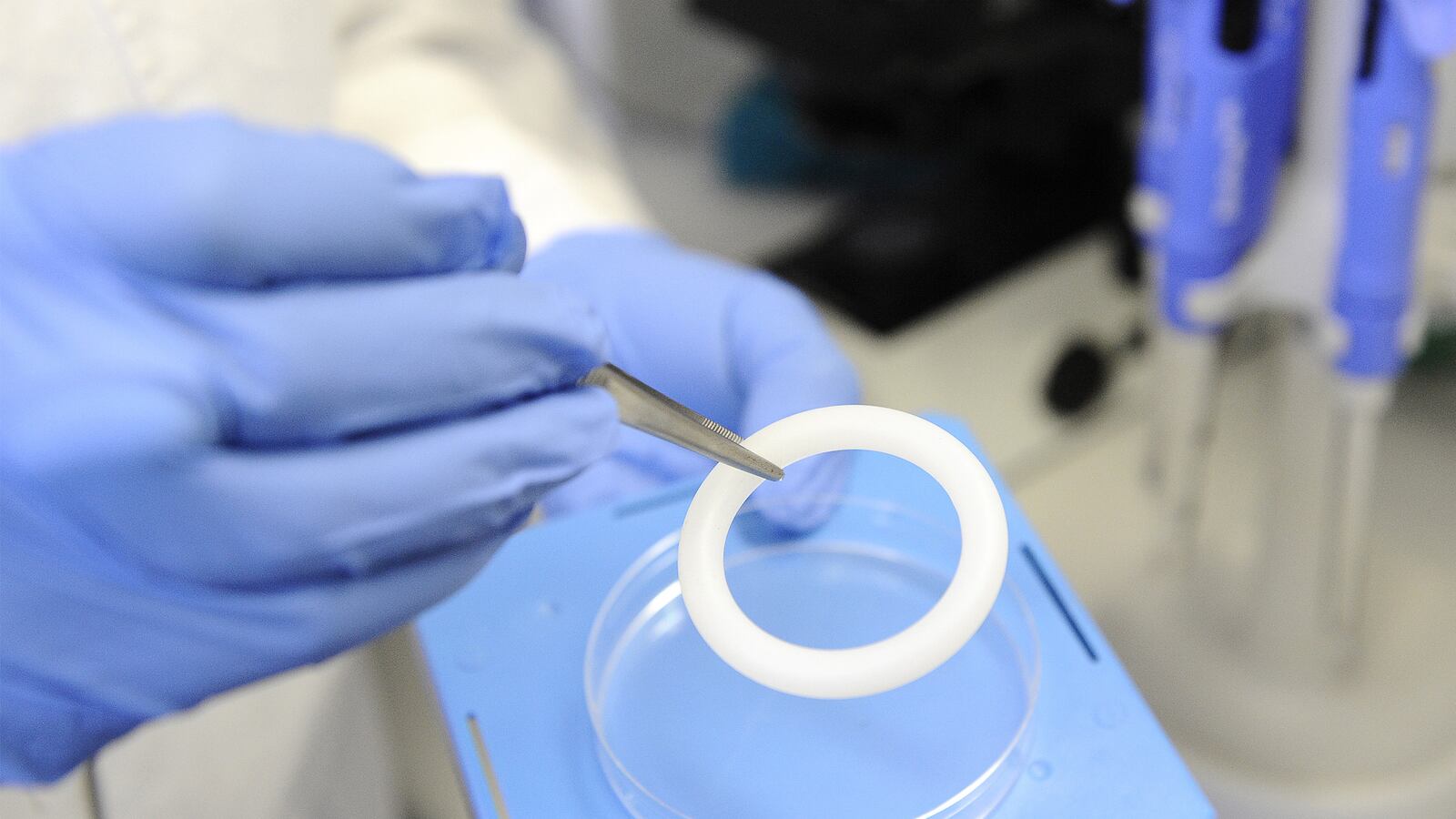

For the last two years, the 32-year-old mother of two had worn a flexible, white, silicon vaginal ring. The goal? To see if a slowly released drug called dapivirine could prevent HIV from vaginal sex.

If it could, Zikhali felt sure that her children wouldn’t experience what she had growing up. HIV had been so taboo during her childhood that she wasn’t permitted anywhere near the homes of people who died from complications of AIDS—entire blocks were off limits to her. She couldn’t even recall hearing anyone utter the words HIV or AIDS in her youth. And yet, according to UNAIDS, nearly 4 million women in South Africa live with HIV.

If the ring had worked, maybe things could be different for her 7-year-old daughter, who already knew that friends’ parents were sick.

“I thought, ‘Well, if I lost a lot of relatives through [HIV and AIDS], this is an opportunity to be one of these women to help find a [way to prevent it],’” she says. “I’m not doing this for myself. I’m doing it for my children, and for all the unborn children.”

So Zikhali sat calmly and listened as the researchers started reading the results of the ASPIRE (A Study to Prevent Infection with a Ring for Extended Use) trial and its sister trial, the Ring Study.

Twenty-seven percent. That was the overall drop in HIV rates among women who received the dapirivine ring, compared to those who had received a placebo.

Sixty-one percent—the drop in HIV rates for women Zikhali’s age, 25 and over.

Fifty-six percent—the drop in rates for women 21 to 25. (There was no change for women under 21, the most at-risk group.)

A thrill shot through her. It wasn’t perfect, she knew that. The effectiveness rates could have been higher. And maybe—maybe they would be.

“I thought for that moment that I was happy, and the reason I was happy was: what if instead of 61 percent, it could have been 85 percent if used correctly?” Zikhaili tells me. “Maybe it could be a totally different story [than 27 percent]. Maybe the results would be something we didn’t expect.”

The researchers who conducted the trial wonder the same thing. And today, they may find out if they’ll get the chance. Officials at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) will meet to decide whether it’s a good use of NIH’s money to fund follow-up studies.

As recently as a week ago, additional funding was uncertain. People close to ASPIRE said 27 percent effectiveness rates might be considered too low for further study.

It’s possible NIH officials will decide that ASPIRE is just another failed study in a long line of failed studies on HIV prevention in women. After all, years earlier, researchers sat in a larger meeting room at Wits RHI and announced they were stopping another study—this one on the HIV prevention drug Truvada—because few women were taking the drug, and they couldn’t draw conclusions.

Researchers and advocates have been bruised by those past battles, says Dr. Judy Auerbach, professor in the Center for AIDS Prevention Studies at the UC San Francisco School of Medicine. So when researchers and advocates began receiving “negative signals” from the NIH about ASPIRE, they pushed back, says Dazon Dixon Diallo, the executive director of the Atlanta-based women’s nonprofit SisterLove, Inc. Dixon Diallo has been invited to attend today’s NIH meeting.

But Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which funds research, tells a different story. He calls the vaginal ring trials “a very important potential intervention” against HIV in women. And he expects that the NIH will fund those follow-up studies—though the decision may not be publicly announced this week.

“I don’t want to jump ahead of the meeting, but what will likely happen is that there is something more we’d like to do here,” says Fauci. He cited the iPrEx study, another NIH-funded HIV prevention trial, which showed that Truvada was effective in preventing HIV transmission in gay men and transgender women. In iPrEx, they funded a type of study called an open-label extension study (kickily referred to as an OLE trial). “We will likely do something like that” for ASPIRE, too, he says.

If that’s true, when National Women and Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day happens tomorrow, there may be one more thing to celebrate.

***

To understand why a follow-up of the original ASPIRE trial might mean different results, consider how weird it is to participate in a clinical trial.

Imagine you’re a woman. In fact, imagine you’re Phiwe Zungu, a 25-year-old schoolteacher in Johannesburg. You walk into the health clinic where you get your birth control pills and an employee asks if you want to participate in a clinical trial to help women prevent HIV.

If you’re Zungu, you are all in. “I’m a feminist,” she says. “I generally like most things meant to empower women.”

But then you meet with the researcher and she holds up a thick, silicon ring and your eyes widen. “It looked big,” Zungu says, laughing. “So I was like, ‘OK, uh, is this going to be comfortable?’”

Then they tell you to wear the ring every day, all day—during sex, your period, everything. In fact, wear it for two years. You might have side effects—everything from incontinence to weird discharge and vaginal bleeding. Let us know. Come in once a month, and we’ll give you a new ring. Oh, and by the way, we don’t know if we’re giving you the ring with dapivirine in it, or if you’re just putting a random piece of silicon in your vagina. And we don’t know even if dapivirine will actually work.

It turned out that the ring was comfortable, so much so that Zungu said she put it in and totally forgot it was there until it was time to return to the clinic to receive a new one. Her boyfriend didn’t mind it, either. And neither Zikhali nor Zungu said they had any side effects from the ring, something consistent with study results (though, to be fair, neither women know yet if they received the dapivirine ring or placebo).

Still, it would be understandable for participants to be skeptical. “Am I going to be a guinea pig?” Zikhali says she wondered at the beginning. It might even be understandable if they didn’t use it at all.

Clinical trials are an act of faith on both sides, says Dr. Robert Grant, lead investigator of the iPrEx trial. The truth doesn’t come out until the end of the trial, when researchers learn who received active drug and who received placebo, as well as who had enough drug in their system to prove that they actually used it.

It wasn’t until the iPrEx OLE trial results in 2014 that Truvada’s proven effectiveness shot up from 41 percent in the initial trial to more than 90 percent in iPrEx OLE. Being able to tell participants that they’re not only getting the real drug, but also that it works, can change how people use it, Grant says. And that can change effectiveness rates. It did for Truvada: with iPrEx OLE, the more you used it, the more effective it was.

That’s what the researchers of the ASPIRE trial want to figure out.

“Finishing one of these large trials answers the very first questions—whether the new prevention approach is safe and effective,” says Dr. Jared Baeten, the lead researcher on the ASPIRE trial. “But then a whole set of new questions open up, many of which cannot be anticipated before the first questions are answered. We have really important next step work to do and I’m optimistic about the next steps.”

***

When Auerbach first read the results in advance of CROI, the big U.S. HIV conference in February, her first thought was, “Here we go again.”

Another hopeful study, another moderate result, another question about why young people, especially young women, don’t use HIV prevention tools. More uncertainty about whether there’d be funding to get the answers.

It happened in 2010 when CAPRISA 004, a study of an HIV-prevention gel, showed only 39 percent overall effectiveness. The following year, the initial results of iPrEx were only 41 percent. In 2015, the FACTS 001 trial, designed to confirm CAPRISA’s results, found no effectiveness, largely because women didn’t use it enough. And then there are the two trials of Truvada in women—VOICE and FEM-PrEP—which stopped early because not enough women were using the drug to draw any useful conclusions. The buzz, Auerbach told me in 2014, was that PrEP doesn’t work in women.

So Auerbach wasn’t surprised when, at CROI, the ASPIRE presentation was met with a standing ovation by some and silence by others.

“There’s no consensus in the field of what to do when there are moderate efficacy levels,” says Auerbach, who wasn’t involved in the ASPIRE trial. “How do you even interpret the findings? That’s what I was hearing at the conference—there was this, ‘The cup is half empty,’ and ‘The cup is half full’ thing happening, and your reaction to the results depended on where you land on that question.”

It’s something that advocates for woman-centered HIV-prevention methods have heard for decades.

Anna Forbes, a staff person for the U.S. Women and PrEP Working Group, has been working for more than 20 years on so-called microbicides (that’s what the ring is—HIV prevention medicine applied directly to the site of exposure). And for 20 years, she and activists like Dixon Diallo have been fighting the idea that these formulations are, well, gross.

“It’s an association with women and contraception, and what people on [Capitol] Hill told us was the ‘Ick factor,’” she explains. “That something would be inserted into the vagina or into the rectum is not perceived as clean in the same way that a pill you can take orally is.”

It’s not lost on Forbes that, of all the prevention studies showing moderate effectiveness in recent years, it was a study on gay men that received follow-up funding. CAPRISA did have an OLE trial, too, the results of which results have not yet been announced.

“Many people are cynical because they’ve been through this battle before,” Auerbach says. “Honestly, I think there’s an underlying concern about a certain level of sexism or gender dynamics at play in how the results are interpreted, and by whom.”

So when the ASPIRE trial results were unblinded and there was an inkling of hesitation from NIH, activists moved, says Dixon Diallo.

“The minute we got the news and thought we were getting negative signals from the NIH, we started to raise our voices,” she says. “It was informal, kind of like a whisper campaign. A ‘We’re watching you’ kind of thing.”

***

NIH’s Fauci has gone on record calling the ASPIRE results in women under 21 “disturbing.” But when he spoke to The Daily Beast, he said he’d “have to respectfully disagree” with any insinuation that the NIH isn’t committed to HIV prevention in women.

“You’re confusing the concept with the data,” he says. “We’ve always been enthusiastic about the concept of microbicides. But up until now, the data have been disappointing. Now we have a complicated but positive signal of HIV prevention [with ASPIRE] that seems age distributed.”

He said the 61 percent effectiveness in women over 25 is the “anchor” they need to fund follow-ups.

Aside from the OLE trial, already called HOPE, Fauci says he wants to get to the bottom of why the ring showed nearly no efficacy in women under 21.

“Is it that young women don’t use it as often or as consistently as women who are 25 or older?” he says. “Or is there something biologically different in late teenagers? I tend not to think so, but we can’t assume anything.”

Auerbach, who has done research on women’s preferences for HIV prevention methods, agrees. It’s critical, she says, to start with young women’s perceptions and preferences first, and not try to force products on them that they don’t want or aren’t appropriate.

And Dixon Diallo, who compares HIV rates among young, southern African-American women to women in Africa, keeps returning to her concern about getting prevention right for young women.

“We have a long way to go to figure out what they want, what they need, how they need it, and what will make them use it,” she says. “I can honestly say I’m really happy to hear that that’s the way the NIH is thinking [about ASPIRE]—that they’re still interested in investing to continue to expand and learn what it will take to meet these women’s needs.”

***

Fauci sees a future in which we have a tool specifically for women that matches how well Truvada has worked in, mostly, gay men. Though Truvada does prevent HIV in women (and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 460,000 American women need it), a recent study out of the University of North Carolina found that women need to take it six days a week to achieve the same level of HIV protection that gay men get with four-day-a-week use.

“We take very, very seriously the issue of women and HIV,” Fauci says. “We’ve been hoping for a woman-controlled intervention. We need more of that in societies, especially those where women are somewhat disenfranchised.”

No one knows if the ring is that tool, and it’s not the only one in development. The Microbicide Trials Network (MTN), an NIH-funded network designed to develop and test HIV-prevention methods in women, has nine studies in development or enrolling participants. Some of them are gels, while others are films and other products meant to carry both HIV prevention and hormonal contraception to women at the site of sex.

But with the NIH’s decision today, we may see something we’ve never seen before: an HIV prevention method in women that’s been shown to work twice. If the OLE is successful, NIH’s funding could bridge clinical research and wide availability of the ring to women in communities with the highest rates of HIV in the world, says Sharon Hillier, co-principal investigator of the Microbicide Trial Network.

For Zikhali, that’s a sea change—one that can’t come fast enough.

“[The ring is] a sign that we’ve taken one step toward finding a cure, to find something to suppress the pandemic,” she says. “I hope one day, we will have a solution, and I hope one day I can tell my daughter that I was part of that.”