A close look at most great 20th-century novelists and playwrights will reveal lives, for better or for worse, well lubricated with alcohol. Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Truman Capote, Eugene O’Neill, Hunter S. Thompson, Tennessee Williams, Ian Fleming, Dorothy Parker, John Cheever, Charles Bukowski, Sherwood Anderson, Walker Percy, James Baldwin, Raymond Chandler, Graham Greene, Jim Harrison… The list goes on and on. Prominent on that roll call is, of course, William Faulkner, who would have turned 119 this weekend.

For these legendary writers, it became de rigueur to drink, often to excess. Fitzgerald noted that for the American writer, “the hangover became a part of the day as well allowed-for as the Spanish siesta.” Yet this affliction—er, condition—among writers goes back to ancient times. It was the great poet Horace (65-8 B.C.) who observed that, “No poems can please nor live long which are written by water-drinkers.”

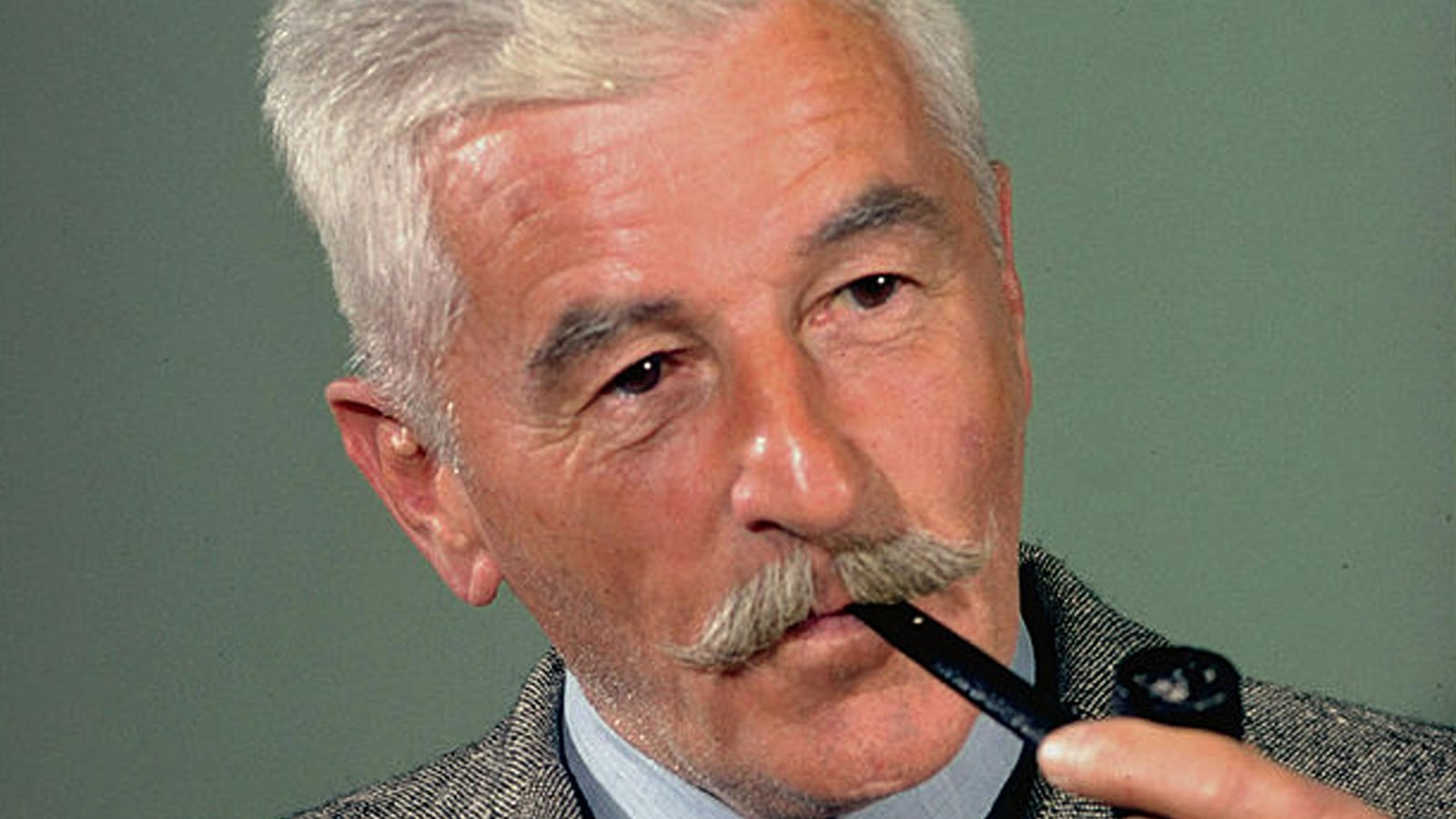

Faulkner is one of the greatest writers of this generation, penning such classics as The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, Light in August, Sanctuary, Pylon, Absalom, Absalom!. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949 and twice won a Pulitzer Prize, in 1955 for A Fable, and again in 1963 (posthumously) for The Reivers. He was born in New Albany, Mississippi, a small town not far from Oxford, where he lived most of his adult life.

Faulkner came to personify the Southern Gothic genre of American letters, adopting that dark, brooding, occasionally disturbing, always complex style, redolent of hoary old oak trees and Spanish moss. His novels and stories were consumed with the ideals, reputations, and legacies of families that were falling apart like the decrepit plantation homes in which they lived. Through them, he came to represent the old-line gentleman of the post—Civil War Southern aristocracy.

A big part of that persona manifested (again, for better or for worse) in Faulkner’s relationship with good-old Southern whiskey. In his 1927 New Orleans—based novel Mosquitoes, he throws out a fitting rhetorical question: “What is it that makes a man drink whisky on a night like this, anyway?”

“There is no such thing as bad whiskey,” Faulkner once reasoned. “Some whiskeys just happen to be better than others. But a man shouldn’t fool with booze until he’s fifty; then he’s a damn fool if he doesn’t.”

Indeed, the man loved his whiskey. Too much. It became a muse and a constant writing companion. In 1937, he explained his method to his French translator Maurice Edgar Coindreau: “You see, I usually write at night. I always keep my whiskey within reach; so many ideas that I can’t remember in the morning pop into my head.”

To some of his critics (not to mention his rivals), this method was a double-edged sword. During an interview with Hemingway during the mid-1950s, when he was asked if he made himself a pitcher of Martinis before each writing session, Hemingway snorted, “Jeezus Christ! Have you ever heard of anyone who drank while he worked? You’re thinking of Faulkner. He does sometimes—and I can tell right in the middle of a page when he’s had his first one.”

Faulkner did say that “civilization begins with distillation;” perhaps his writing sessions did, too. He was known to go on long drinking binges where he would lock himself into, say, a hotel room and drink for days straight. While booze may have been Faulkner’s inspiration, it surely took a toll on his health and years off his life. During a 1937 visit to the Algonquin Hotel in New York, after a days-long bender, he passed out against a steam radiator and severely burned his back. He took the unfortunate incident with his typical sense of humor. His friend Bennett Cerf, one of the founders of book publisher Random House, chastised him: “Bill, aren’t you ashamed of yourself? You come up here for your first vacation in five years and you spend the whole time in the hospital.” Faulkner quietly replied, “Bennett, it was my vacation.”

As a young, undiscovered writer, he lived in the mid-1920s in New Orleans, which was then a mecca for young literary talent, sort of a Montparnasse of the Delta. He and his roommate, William Spratling, lived in the very bohemian French Quarter and mixed bathtub gin with Pernod for their drinking soirees.

But Faulkner (famously) was primarily a whiskey drinker, be it a fine aged bourbon or a crude jug of corn moonshine.

And he knew where to find it, even on a Sunday in a dry corner of Mississippi. Author Shelby Foote had invited Faulkner to attend an observance of the 90th anniversary of the start of the Civil War battle Shiloh, which neither gentleman wanted to do without liquid courage. Foote was at a loss as to how to get a hold of some whiskey, since it was a Sunday. Faulkner, on the other hand, saw a man getting his shoes shined and reasoned, according to Foote’s recollection in Conversations with Shelby Foote, that “anybody getting his shoes shined on Sunday morning would know where it was.” Sure enough, when asked where the town bootlegger could be found the man replied, “Well, I was fixing to go out there myself. If you could give me a ride, I’ll show you the way.” And before too long ol’ Bill and Shelby had themselves a pint of Old Taylor and some Cokes for chasers.

Though he wasn’t afraid to drink whiskey straight, Mint Juleps cooled him on notoriously hot Mississippi afternoons. So much so, in fact, that Faulkner’s recipe for the cocktail resides on a typewritten card, next to his metal julep cup on a shelf in his Oxford home. Quite simply, the card reads “His recipe was: whiskey, 1 tsp Sugar, ice, mint served in a metal cup.”

Faulkner also had a special “medicinal” drink for colder temps, when he or one of his relatives were under the weather. It seems the author’s Hot Toddy, according to his niece Ms. Dean Faulkner Wells’ book The Great American Writers Cookbook, could cure anything from “a bad spill from a horse to a bad cold, from a broken leg to a broken heart.”

“Pappy alone decided when a Hot Toddy was needed, and he administered it to his patient with

the best bedside manner of a country doctor. He prepared it in the kitchen in the following way: Take one heavy glass tumbler. Fill approximately half full with Heaven Hill bourbon (the Jack Daniel’s was reserved for Pappy’s ailments). Add one tablespoon of sugar. Squeeze 1/2 lemon and drop into glass. Stir until sugar dissolves. Fill glass with boiling water. Serve with potholder to protect patient’s hands from the hot glass. Pappy always made a small ceremony out of serving his Hot Toddy, bringing it upstairs on a silver tray and admonishing his patient to drink it quickly, before it cooled off. It never failed.”

While raising your glass this weekend to toast Faulkner’s birthday, ponder a line from his first novel, Soldier’s Pay: “What can equal a mother’s love? Except a good drink of whiskey.”

Cheers to that.