A Belarusian currency speculator named Pavel Boguslavovich Belogour is buying up huge swaths of tiny Vermont—thousands of acres of the Green Mountain State, and even patches of land over the border in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

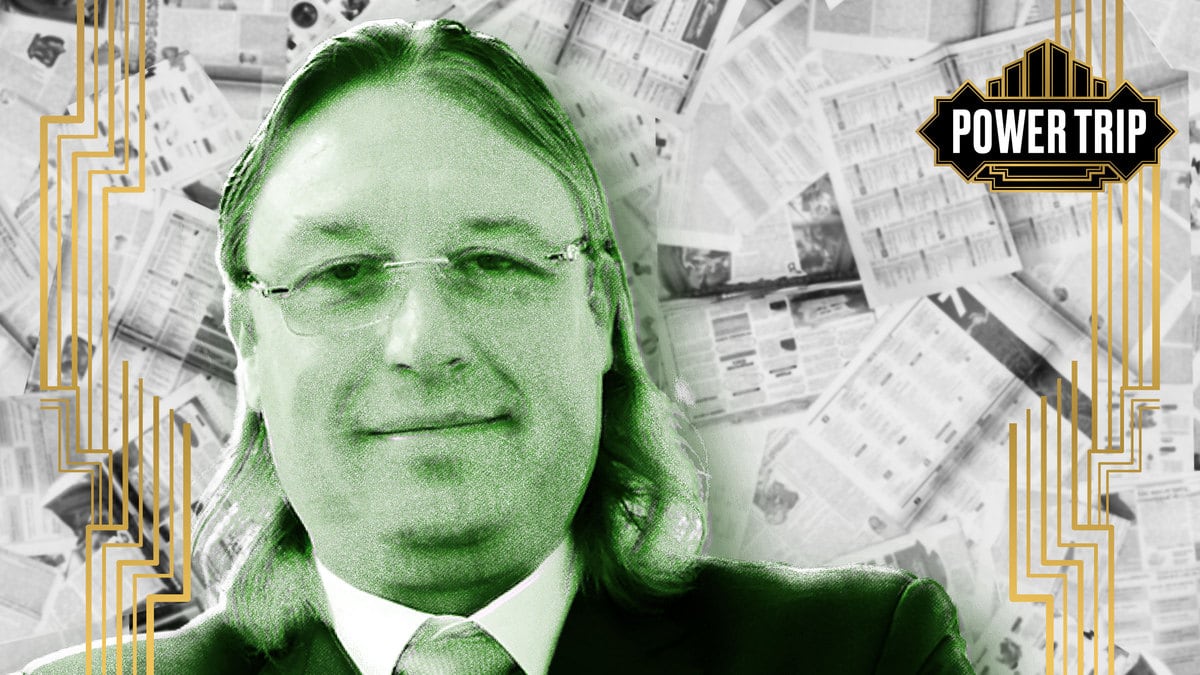

At first, Belogour, who goes by “Paul,” was received as something of a novelty. An idiosyncratic character with long hair and scant online footprint, he had amassed a small fortune in the largely unregulated world of foreign exchange trading—and then came to Vermont to spend it in eccentric ways. He bought a maple sugar farm, an entire marina, and a plot of undeveloped wood, where he planned to build, among other things, a Viking-themed “luxury hideaway,” which he describes as “the Disney of the North.”

“His choices of what to invest in are certainly eclectic, I would say,” Brattleboro Selectboard member Tim Wessel told The Daily Beast. “Clearly he likes the water, so he bought a marina. And clearly he likes beer, so he bought a brewery. It’s kind of like, well, if I had that kind of money, maybe I’d be doing the same thing.”

But a few months before the pandemic, Belogour’s shopping spree accelerated. The 50-year-old multimillionaire, whose exact net worth is unknown, joined the crowd of billionaires and oligarchs looking to buy up rural property, and began closing real estate deals at a rapid clip. In the past two years alone, the foreign exchange trader has snagged more than 3,100 acres across three Vermont counties, including 10 buildings, lots, and businesses, at a cost of more than $3 million.

“Vermont only has 635,000 people,” said Dan Normandeau, a realtor who worked with Belogour on three different properties. “Brattleboro itself has somewhere around 12,000 people. So no, we don’t see that. I shouldn’t say it never happens, but it’s certainly caught people’s attention.”

The rapid consolidation of land became a cause for some concern: “You hear things like, ‘Oh my God, that guy from Gilford is buying all this property,’” said Jeff Potter, publisher of the local nonprofit newsroom, The Commons. Facebook groups for local Vermonters filled with speculation about his acquisitions, history, and motives. Many were supportive; more than a few skewed xenophobic. One Brattleboro resident, who asked not to be named, said locals had coined an inaccurate nickname, “the Russian,” even though Belogour hails from Belarus. He’d hear, “The Russian bought this, the Russian bought that,” he said, “the Russian bought the outlet center on the highway, the Russian bought the mattress store.”

Mounting curiosity about Belogour’s properties reached fever pitch earlier this month, when four local news outlets—several of which had reported on Belogour himself—announced that he had bought them all. In total, he acquired two local newspapers, The Brattleboro Reformer and The Bennington Banner; a weekly called The Manchester Journal; and the bi-monthly UpCountry Magazine. On Friday, the currency trader with no prior news experience was named president and publisher of all four.

The announcement spurred a new round of worrying. One blogger wondered whether Belogour shared the Belarusian government’s attitudes toward media censorship. But other concerns were more justified—in 2015, the same papers had sold to a subsidiary of Alden Capital, the hedge fund dubbed “one of the most ruthless of the corporate strip-miners seemingly intent on destroying local journalism,” which had gradually trimmed their budgets, in one case, leaving just a single reporter to cover an entire county.

In Bernie Sanders’ home state, Wessel said, many residents are skeptical of the influence of outside capital, particularly from the finance industry. “There’s a lot of progressive thinking here,” he noted, “a lot of anti-capitalist thinking.”

Belogour first encountered Vermont in 2008, when he and his wife bought a farm just south of the state border in the town of Bernardston. Though the land is technically in Massachusetts, Belogour frequently crossed the border into Brattleboro. “If you want to go get groceries,” he told The Daily Beast, “it’s closer to me than anything else in Massachusetts.”

After a few years, the trader started to buy some other properties—in 2016, he bought Norm’s Marina along the Connecticut River in Hinsdale, New Hampshire—before zeroing in on southern Vermont. In addition to the four papers, Belogour has bought 1,600 acres in Halifax, 1,500 acres in Guilford, a former Knights of Columbus building in Rutland, a brewery in Springfield, an ex-marble factory in Proctor, and seven properties in Brattleboro, including a former handbag factory and a mattress store. Earlier this year, he bid $3.95 million for a former college campus in Bennington, but lost the auction to a medical provider.

Belogour’s properties are now so numerous that he isn’t sure of the exact number. “I don’t know,” he told The Daily Beast. The forex trader initially guessed he owned “seven or eight properties in Vermont,” then adjusted it to “eight or 10 properties.” It is at least 12, not counting the land in New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

The rationale for his purchases, Belogour said, was primarily conservation. “I like to conserve land,” Belogour said. “I don't like when land goes into the hands of loggers or developers, so any time I could, I just buy a parcel of land.” But he has also set up several businesses, including a brewery called Vermont Beer Makers, a syrup vending website called VermontMapleSyrup.com, and an incubator called the Vermont Innovation Box, which aims to workshop local start-ups, though none has joined so far.

But Belogour’s magnum opus is his “Viking Village,” which he has been constructing on a parcel of his Guilford property. The themed tourist destination, slated to open this summer, will be equipped with Nordic cabins, a communal “mess hall,” ATV tours, dog-sledding, and historical reenactors, who will perform traditional ceremonies and staged Viking combat. “I have been approached now by pretty much every Viking organization in major cities,” Belogour said. “I didn’t know anything about the Viking followers in the U.S.—huge!”

There is little historical evidence to suggest Vikings, who did settle in North America in the early 10th century, ever descended far into what is now the United States. But that doesn’t bother Belogour. “The Vikings were not in Vermont? That’s fake news,” he said. “Let me tell you the truth: Vikings technically were the first Europeans that encountered Northern America, in what we call Newfoundland. They stayed there for about three to five years and then they disappeared. Well, where did they go? We found them in Guilford, Vermont.”

For a successful financier, there is relatively little information about Belogour on the internet. A Nexis news search for his name primarily turns up real estate listings, and a handful of articles from 1996 when, as an economics student at Northeastern University, Belogour was awarded his own patent for developing a shock absorber for roller skates. On YouTube, his name turns up footage from a defunct annual fashion show called “Miss UniTrader,” which convened in China to debut, according to one caption, “the most beautiful Ukrainian girls.”

A local reporter in Brattleboro, who declined to be named due to the investor’s newfound influence in regional journalism, described searching his name on a records database. “Nothing. It's like he’s wiped his entire—it’s like he’s opted out of everything,” the reporter said. “You search for ‘Paul Belogour’ and you get what looks like a very curated reputation or sanitized search history.”

According to Belogour’s LinkedIn, he entered the foreign exchange industry shortly after college, working at the Bank of Boston for six years, before establishing his first forex firm. “It’s the largest market in the world, a daily volume of $7 trillion dollars—it’s captivating,” Belogour told The Daily Beast of the appeal. “That’s what drives the world: foreign exchange.”

Belogour sold his company in 2004, but continued working there until the 2008 recession. Around that time, the trader and his wife left the Boston area for their farm just south of Vermont’s border. There, he began developing a trading software called UniTrader, and opened a second forex company, Boston Merchant Financial Ltd, or BMFN (the “FN” stands for “financial”). Part of the appeal of BMFN, according to Forex platform reviews, was its leverage: 400:1, meaning a client could invest just $1,000, but trade with as much as $400,000.

Belogour told The Daily Beast that he sold BMFN five years ago, declining to name its new owner. But his time at BMFN was fraught with legal challenges from regulators and competitors. Between 2012 and 2015, BMFN faced three federal lawsuits—detailed in court records and a robust investigation from the nonprofit outlet VTDigger.

Two of the lawsuits alleged that BMFN had refused to let them withdraw funds, while a third claimed Belogour had conspired to steal trade secrets. Of the former, one settled out of court for an undisclosed sum; the other was dismissed after a judge determined its jurisdiction should not have been the United States, but Switzerland. The latter suit was dismissed by a judge, after the plaintiff acquired a stake in Belogour’s software company.

The company has also encountered conflict outside of court. There’s a Facebook group with several dozen members called “BMFN victims,” where users list complaints of wrongfully frozen funds and missing investments. A search for “BMFN” on Forex review websites turns up myriad forum discussions detailing similar complaints. Of the allegations, Belogour told The Daily Beast: “A lot of people have complaints. Some reasons are valid, some not valid,” he said. “I don’t know. I’m not aware of any of the people that have issues.”

Though Belogour insists he cut ties with BMFN, business filings show that he continues to operate an LLC out of Massachusetts by the same name. Corporate records filed in Massachusetts indicate that the entity was established in 2016 and remains active. The most recent annual report was filed in January. In fact, many of Belogour’s more recent property purchases list “BMFN LLC” on the deeds.

Belogour also continued to list BMFN as a current workplace on LinkedIn and in his corporate bio on websites for his other companies. He also confirmed to The Daily Beast that he uses a BMFN email address. Asked about his LinkedIn profile, Belogour said: “Yes, I don’t know, I have a lot of companies on LinkedIn… The way I look at LinkedIn, the way I present information, is where I work. So if LinkedIn says this is where I’m working, so be it.”

Many Vermonters are less concerned with how Belogour made his money than excited by what he has done with it since. Belogour’s supporters applaud his efforts to refurbish historical buildings and conserve woodland that might be otherwise plundered by industry. Many of the properties Belogour bought had been undervalued, Brattleboro Selectboard member Tim Wessel said. The marina, for example, had been on the market since the death of its owner at a fairly low price. And for years, the outlet center, a no-frills former handbag factory, had languished on the outskirts of town—the first building visible to travelers driving up from Massachusetts.

“It’s literally the first building when you get off Exit 1,” Wessel said. “And since the mid 1990s, it has just looked terrible. But he’s fixing up rather nicely.”

Other boosters tout Belogour’s significant effort to hire locally—nearly all of the contractors he’s hired to renovate the properties have come from the nearby towns. “He was sort of generating this entire economy around him, hiring guys to come and build out his village,” one Brattleboro resident said.

By Belogour’s account, this trend will extend to the newspapers as well: he plans to hire more reporters at the papers. In an op-ed for the Reformer, Belogour underscored his belief in the free press, promising that the newspapers would operate with total editorial freedom. “I’m reinvesting,” Belogour told The Daily Beast. “We will definitely be injecting more money into these publications.”

“Until there’s some evidence of a Bond villain status, I don’t think it’s fair to throw him under the bus,” Wessel said. “But he’s got that deep accent and he says funny things. I told him, ‘You know, you’ve been getting beat up on social media.’ And he said, in that Arnold Schwarzenegger voice, ‘Listen: I don’t care.’”