After four years of watching Mitch McConnell’s Senate rubber-stamp a parade of mostly white, mostly male, mostly corporate lawyers for lifetime seats on federal courts, the incoming Biden-Harris administration is racing to fill federal judgeships and to diversify the bench to include public defenders, civil rights lawyers and labor attorneys.

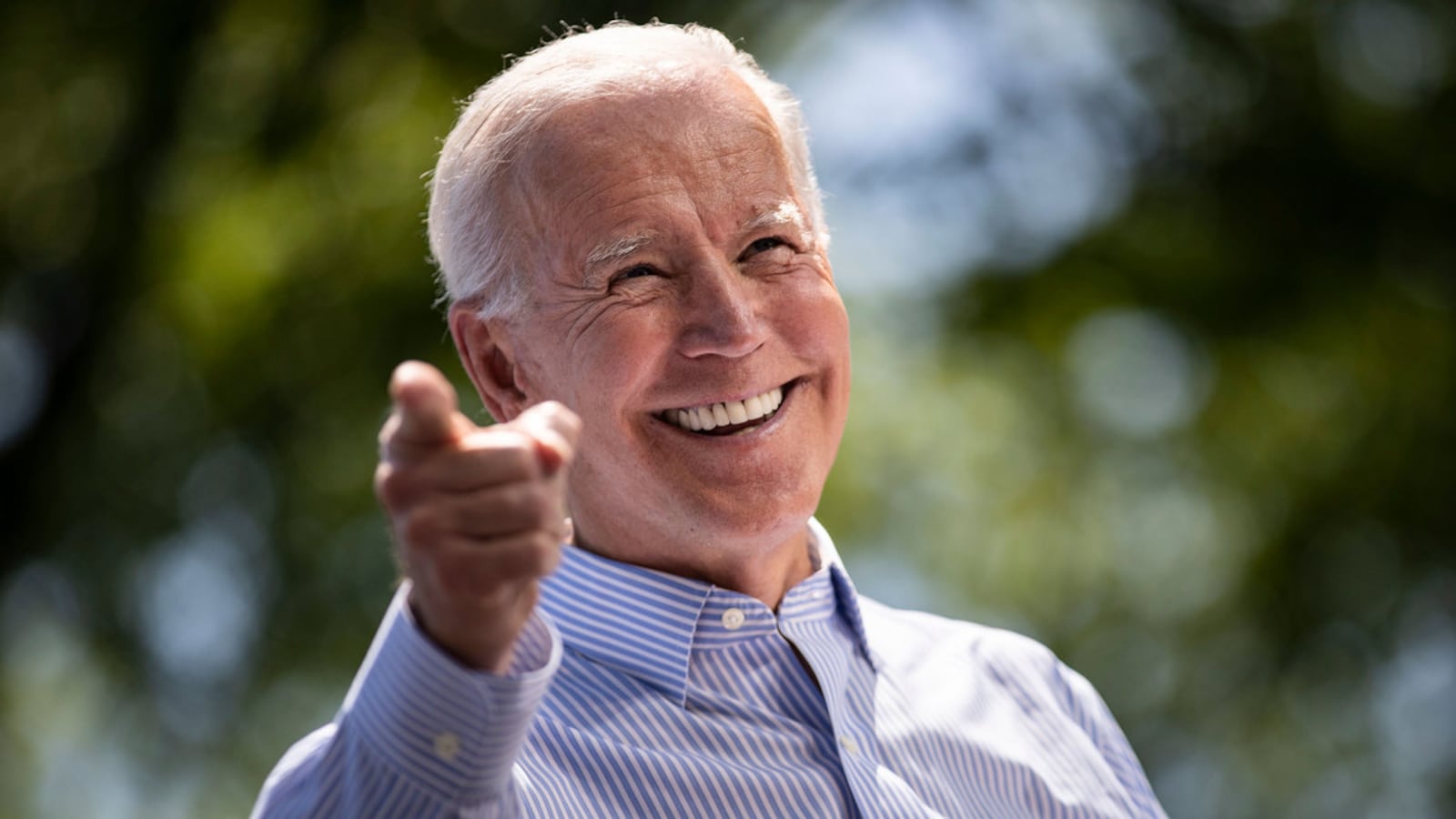

“These are the kinds of lawyers we need to see more of,” says Chris Kang, co-founder of Demand justice, a progressive advocacy group. He commends President-elect Joe Biden’s incoming White House legal counsel, Dana Remus, for putting Democratic senators on notice in a pre-Christmas letter about doing their part to fill 43 District Court vacancies by recommending nominees that fit this new diversity by Jan. 19. “It’s sort of revolutionary to set these markers and to do this before his administration even takes office,” says Kang.

Kang, who oversaw judicial appointments in the Obama White House, says that “there’s no question President-elect Biden is taking a much stronger and more affirmative approach in re-balancing our judiciary.” The letter from Remus asks Democratic senators to submit three names that represent professional diversity within 45 days after every District Court vacancy.

McConnell, whose slogan was “leave no vacancy behind,” focused on the circuit courts, where the Federalist Society and other conservative groups wanted to place their ideologues and plant their flag. That’s been done, but as Trump’s term nears its end there are 43 District Court vacancies, most of them in blue states, including six in New Jersey alone, 13 in California, five in Washington state, two in Massachusetts—you get the idea.

The District Court seats “remained vacant because if you’re really into legal theory and legal precedence, (the circuit courts are) where the Federalist Society puts its emphasis,” says Russell Wheeler, a visiting fellow with the governance program at the Brookings Institution. But “if you’re a small business owner in New Jersey trying to get a patent, you need district courts.”

They also remained vacant because McConnell and Lindsey Graham, who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, did not waive what is known as the “blue slip” tradition for District Court nominees, where home state senators can veto or stall nominations by refusing to return their blue slip. That’s what happened in New Jersey, where Democratic Senators Bob Menendez and Cory Booker have been in a stalemate with the White House over District Court seats, two of which have been vacant since President Obama’s last two years.

“People complained McConnell didn’t give Merrick Garland a hearing. He didn’t give anybody a hearing,” says Wheeler, who says that Obama “just fell off the table” when it came to getting judges confirmed in his last two years, when Republicans controlled the senate.

If the Republicans maintain majority control of the Senate in 2021, Wheeler is not optimistic that McConnell will treat Biden’s nominees any differently than he treated Obama’s. But that’s the point. Pressured by some 70 progressive groups, the incoming Biden team recognizes they need to do things differently.

Daniel Goldberg with the liberal group Alliance for Justice calls the letter from the incoming White House counsel “a welcome signal” that the Biden administration will prioritize judges in a way that past Democratic administrations haven’t. And it’s not just the White House, he says, as Democratic senators “are energized like they haven’t been in the past to make quick nominations and to fight for confirmation. It makes obstructionism harder if they’re sending up names now and putting pressure on McConnell.”

While Obama, who didn’t foresee how much obstructionism he would face, was slow off the mark, Biden, even as he’s voicing optimism, knows what he’s in for. “We’re seeing a greater urgency,” says Kang with Demand Justice. He points to Biden’s own story, where he left a traditional law firm early in his career to become a public defender and how Biden is breaking new ground in calling for a new breed of judges. Biden’s chief of staff also plays a role in prioritizing the judiciary, says Kang. Ron Klain clerked for Justice Byron White on the Supreme Court and worked with Biden when he chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee through turbulent confirmations.

It’s a stark contrast to Rahm Emanuel, who famously dismissed a group of activists urging a stronger push on the judiciary, with Obama’s notoriously foul-mouthed chief of staff telling the group that he didn’t give a you-know-what about judicial appointments.

This time, with Klain on their side and the future White House counsel urging Democratic senators to set up an application process, progressives are more optimistic. The People’s Policy Project reached out to every Democratic senator to see how many used commissions to come up with recommendations. A third did not and half of the two thirds that do wouldn’t reveal who sits on their commissions.

“That’s why there are so many prosecutors and corporate law partners in the pipeline,” says Kang, even when a Democratic president is in office. It’s the old boys’ club and it takes an affirmative effort to make change.

This time could be different, as Biden has set forth his vision for the judiciary and is pressing Democratic senators to join him in finding nominees that can clear McConnell’s blockade, or at least make him feel the heat. They will be of such caliber, says Kang, “It will be even more obscene when Republicans seek to block them because they will be the kind of nominees that progressives will be excited about, and that brings a different dynamic to this fight.”