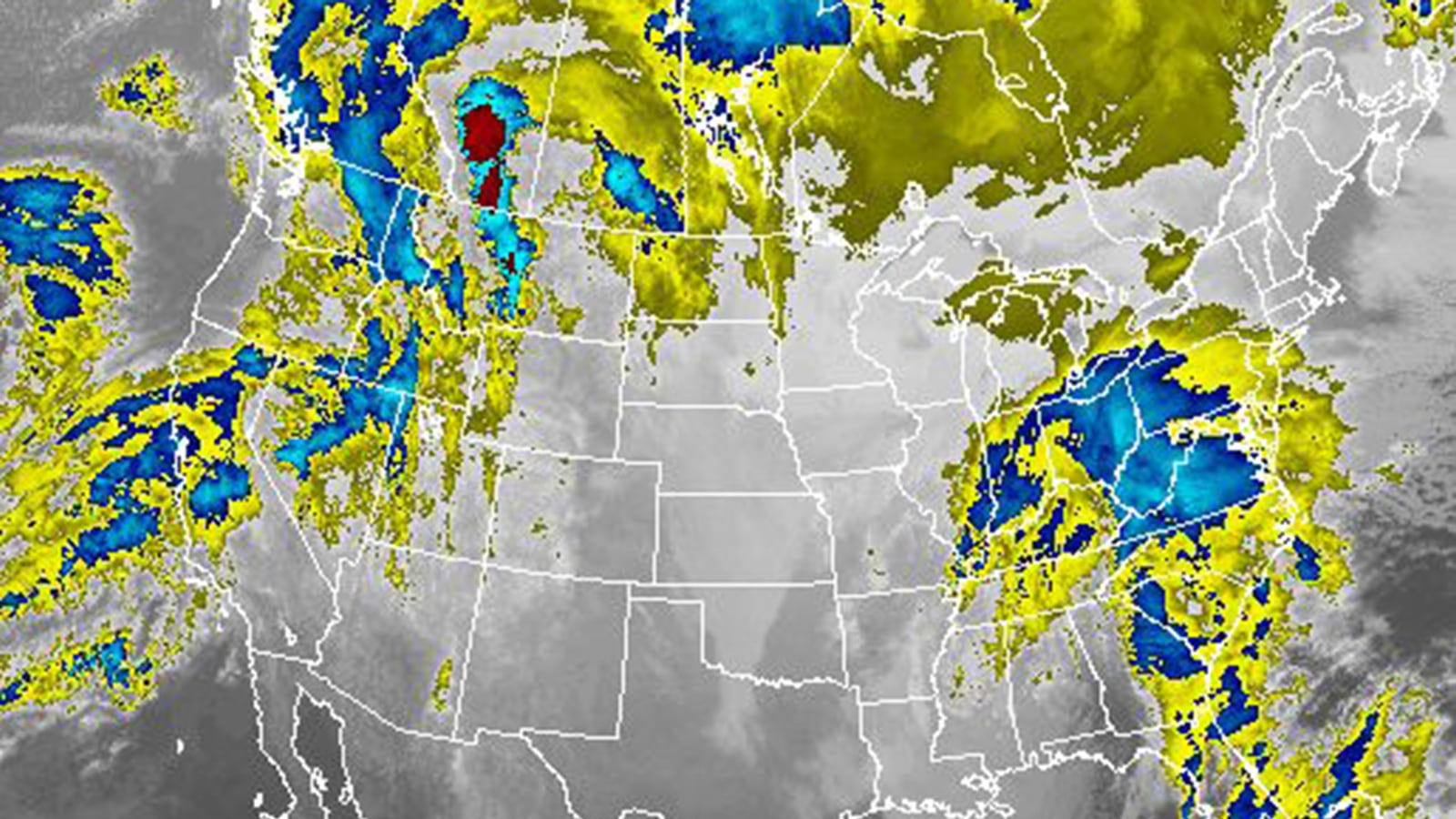

A low pressure system that spurred 60 foot waves for surfers in Hawaii last week has transformed into a winter storm that may dump over two feet of snow on Washington D.C. over the next few days.

In addition to the heavy snowfall and gusty winds extending from the Carolinas to Connecticut, other threats from the storm include ice in the southeastern states and coastal flooding from the mid-Atlantic to Long Island. The National Weather Service has issued blizzard warnings from DC to Long Island, and the NWS offices for Philadelphia and New York City have issued coastal flood warnings. The flooding is expected to peak during three consecutive high tide cycles: Saturday morning, Saturday evening, and Sunday morning.

As has been the case for all of the coastal storms in the eastern US the last few years, sea level rise from climate change has added about an extra foot of water to coastal flooding levels. But shorter timescale climate influences are also making flooding worse during this storm.

El Niño, the tropical phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean that alters weather patterns around the globe, has probably added another four to six inches of temporary sea level rise on the mid-Atlantic coast this season, said William Sweet, an oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Sweet studies the influence of El Niño on sea level, and he says that El Niño provides an atmospheric setup that improves the odds for more east coast storms, as well as a tendency for more constant winds that push more water towards the shore. The combination of more storms and more constant winds tends to lead to more frequent flooding events during El Niño. This storm may bring major flooding to some areas, but even mild to moderate flooding, also known as nuisance flooding, can damage infrastructure and strain budgets.

More flooding isn’t El Niño’s only imprint on this storm. While it may feel like the arctic is descending on the US east coast, influences from points south have just as much to do with it.

For one thing, moisture from the Gulf of Mexico fueled the storm as the system moved across the southeastern US. Looking at origins further west, scientists are hesitant to characterize the storm as being caused by El Niño, but it did likely influence the track of the storm, and perhaps its intensity. The warm waters of the tropical Pacific, characterized by El Niño, set in motion a series of effects in the atmosphere.

One of those effects is on the jet stream during winter over North America, where it takes a more southern track and tends to be stronger than normal, said Anthony Barnston, a climate scientist who studies El Niño at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (disclaimer: I also work there). This storm followed that track, allowing it to gain the moisture from the Gulf of Mexico before heading up the east coast of the country. What is somewhat more unusual for an El Niño year, according to Barnston, is for the storm to reach as far north as New York City.

If El Niño continues its influence on the North American jet stream, this could be the first of several major storms, especially for the southeastern US. Stick your nose out the window and you may just get a whiff of that tropical breeze.