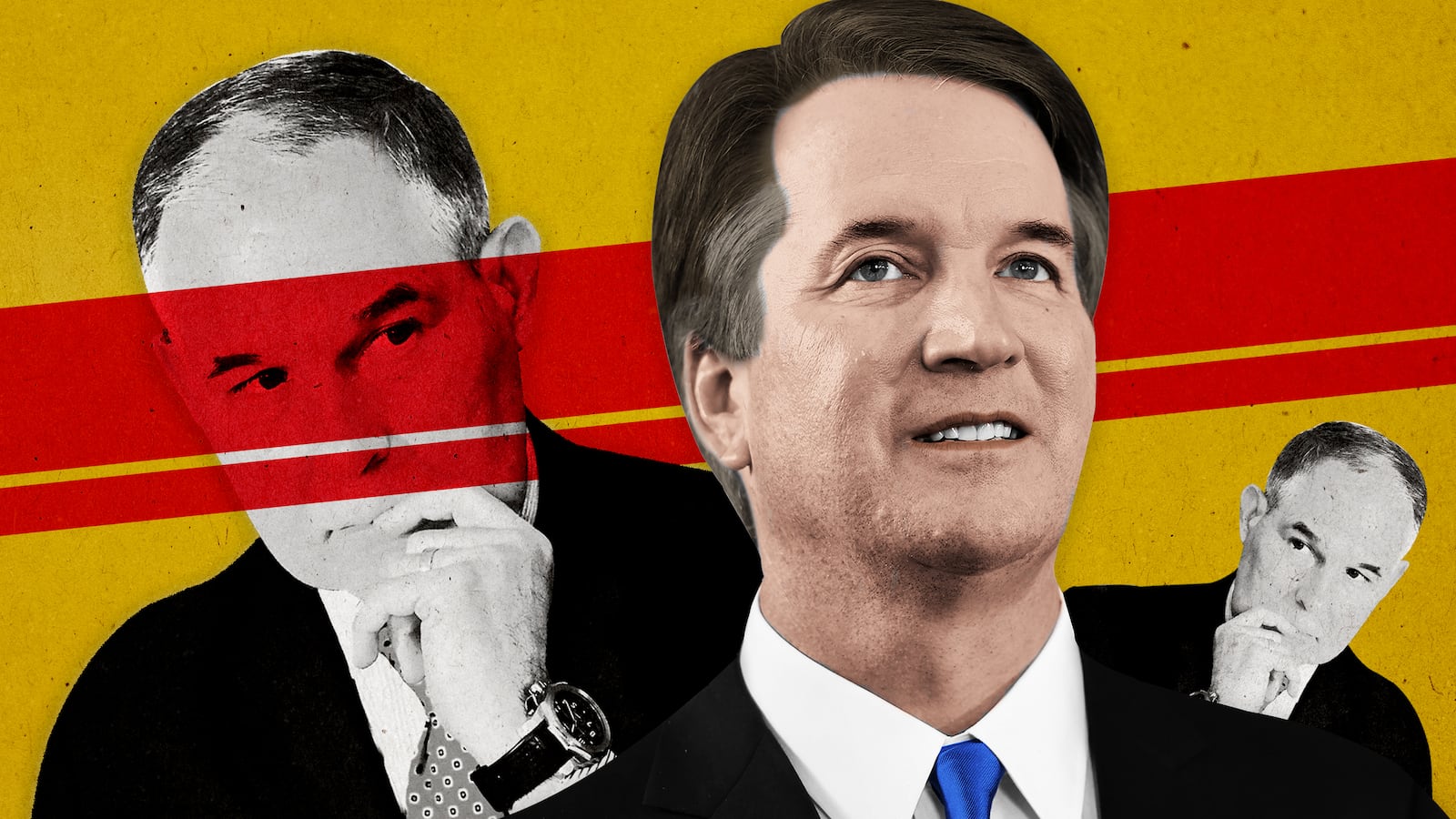

Not surprisingly, most of the coverage of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh has focused on social issues like abortion, LGBT equality, and contraception.

But while Kavanaugh’s record on those issues is sparse and unclear, his record on economic and environmental issues is as clear as a smog-free day: Judge Kavanaugh is like the Scott Pruitt of the federal judiciary.

This assessment is based on a long string of Kavanaugh’s rulings as a judge on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, most of which rely on the premise that, contrary to prevailing Supreme Court doctrine, administrative agencies have very limited discretion to act in the absence of congressional instructions.

That’s how Kavanaugh has been ranked as more conservative than every sitting Supreme Court justice save Clarence Thomas: not because of abortion or same-sex marriage, but because of a long line of cases where he has ruled against environmental, health, and safety regulations and in favor of the businesses regulated by them. For example:

- In 2014, he dissented from the D.C. Circuit’s approval of the EPA’s “Clean Power Plan,” writing that the EPA must consider the costs of cleanup in addition to the environmental benefits. This position became law when the Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Scalia, quoted from Kavanaugh’s dissent and adopted his position.

- In 2012, he wrote that the EPA exceeded its authority under the Clean Air Act by attempting to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. This position, too, was adopted by the Supreme Court in a majority opinion by Scalia.

- That same year, he wrote the decision that struck down a federal rule quantifying how much “upwind” states must clean up air pollution in order to avoid Clean Air Act violations in “downwind” states. He said the EPA’s apportionment of responsibility exceeded its authority. The Supreme Court later overturned that decision and supported the EPA.

- In 2011, he declined to defer to the EPA’s designation of a “critical habitat” for an endangered species of shrimp, even though it was backed up by scientific evidence.

- In 2017, he again ruled that the EPA had exceeded its statutory authority, this time in attempting to regulate hydrofluorocarbons, a major contributor to climate change. “However much we might sympathize or agree with EPA’s policy objectives, EPA may act only within the boundaries of its statutory authority,” he wrote. (That case is being appealed; if it goes to the Supreme Court, Justice Kavanaugh will be recused.)

All that being said, there are four mitigating factors when it comes to Kavanaugh’s philosophy of environmental law.

First, the overriding theme in these decisions is a restrictive view of administrative discretion, not disbelief in environmental science or environmental law. In this way, Kavanaugh is not like Scott Pruitt at all: he is thoughtful, concerned, and aware of science.

In the 2012 case on greenhouse gas emissions, for example, Kavanaugh wrote that “the task of dealing with global warming is urgent and important.” Even though Kavanaugh ultimately voted to strike down the regulations, that position is miles away from the official climate change denialism of the Trump administration.

Kavanaugh is not an anti-environmental ideologue; if anything, he is an anti-regulatory one.

Second, Kavanaugh’s relative lack of deference to administrative agencies cuts both ways. The Pruitt (now Andrew Wheeler) EPA, for example, has been cutting regulations like a lawnmower. As a result, in the short term, the Supreme Court may well be reviewing more anti-environmental regulations than pro-environmental regulations -- and the less deference given to EPA decisions, the less EPA can cut.

Already, in some cases, courts have already rejected these efforts as administrative overreach. Last year, for example, the D.C. Circuit rebuffed Pruitt’s effort to roll back methane regulations without a formal process. Kavanaugh was not part of the three-judge panel that decided that case, but he wrote a similar decision in 2014, in which he invalided an EPA rule that would have allowed polluters to mount a specific kind of affirmative defense. Again: anti-EPA, but pro-environment. In short, because of the Trump administration’s anti-environmental policies, Kavanaugh’s philosophy might actually be a short-term boon for environmentalists.

Third, Kavanaugh’s record is not 100% anti-environmental. In a handful of cases, he has ruled for the EPA. In 2014, he upheld EPA’s plan for mitigating the pollution caused by mountaintop-removal coal mining. And in 2010, he upheld EPA’s review of California’s emission limits.

Finally, since Kavanaugh has amassed a very large body of opinions – he has written 286 opinions, 122 of which deal with administrative law – it is possible to derive various conclusions about his judicial philosophy in general. And the scholarly consensus is that he is more of a case-by-case pragmatist like Justice Kennedy (for whom Kavanaugh clerked, and who appears to have played some role in his selection) than a principled ideologue like Justice Scalia.

Unlike Justice Gorsuch, for example, Judge Kavanaugh has not questioned the general principle of deference to administrative agencies instead preferring to apply it in a narrow way. Again, that’s not exactly a green position, but it is perhaps better than the alternative.

These caveats aside, it’s clear where advocacy groups expect Justice Kavanaugh to land on environmental cases.

Among his biggest fans is the arch-anti-environmental group Pacific Legal Foundation, founded in 1973 by oil tycoons and more recently funded by the Koch Brothers.

“Judge Kavanaugh… has demonstrated the right approach to judging,” said Todd Gaziano, Pacific Legal Foundation’s Chief of Legal Policy and Strategic Research, in a statement. “Justices on the Supreme Court who carefully enforce the Constitution’s protections also ensure the other branches observe the proper separation of powers when they write laws and regulations and take other executive actions.”

In other words, one of the leading anti-environmental groups in the country loves Kavanaugh and his view of the “proper separation of powers.”

The president of EarthJustice, meanwhile, which has filed more than 100 lawsuits so far challenging Trump’s anti-environmental rollback, said in a statement that “Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to take Justice Kennedy’s seat on the U.S. Supreme Court jeopardizes people’s ability to rely on the courts to protect their health, safety, and the environment. In key cases, Judge Kavanaugh has favored unduly limiting federal regulatory powers that are central to keeping Americans safe.”

The question is, with so much attention being focused on a few scraps of statements on abortion, will anyone else pay attention to Judge Kavanaugh’s mountains of opinions against the environment?