LONDON—Arriving in Florence on Friday alongside the leader he is plotting to topple, Boris Johnson will no doubt consider himself a modern-day Niccolò Machiavelli shuffling through the very same cobbled streets where the philosopher crafted a 1513 treatise on realpolitik that would echo through centuries of coups, power-grabs, and back-stabbing.

Britain’s foreign secretary believes himself to be another towering intellect but—viewed from outside the gravitational field of his historically proportioned ego—the blatant and clumsy plots to install himself as prime minister have taken on the air of a tragi-comedy.

Less The Prince; more court jester.

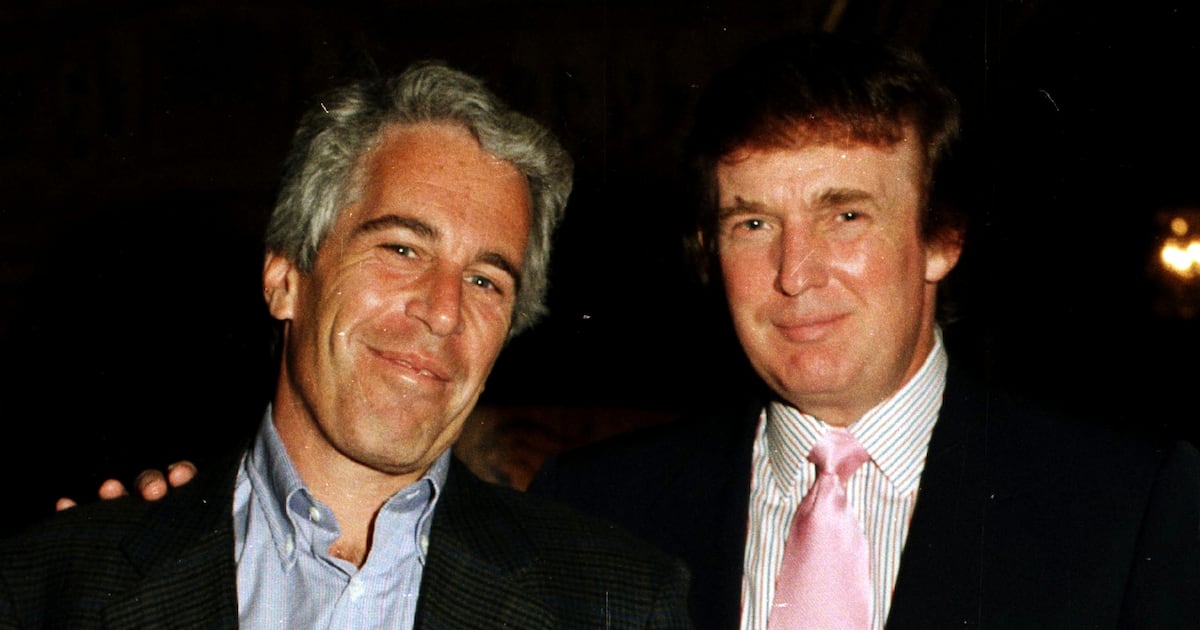

That is not to say that all this blundering will necessarily prove fatal to Johnson’s ambitions. Donald Trump’s current address, after all, is 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

One thing is for sure: Johnson will not stop plotting to become PM.

Under the British parliamentary system, he wouldn’t even have to win a general election to assume that role. He just needs to take over as leader of the Conservative Party. With Theresa May still badly weakened by her electoral humiliation, Johnson knows the position could fall vacant at any time, especially if someone were to give May a little push.

The annual Conservative Party conference next month in Manchester will be one of the most eagerly watched for decades as plots and counter-plots are hatched in the bar of the Midland hotel.

The awkwardness of Johnson’s latest attempt to hurry May out the door was captured by a moment of farce inside an elevator at the W hotel on Lexington Avenue in New York. British broadcast journalists were on their way to interview his boss, May, on the 18th floor when the foreign secretary came bounding into the lobby after an early morning run.

What followed was a sweaty exchange in which Johnson—in shorts and a T-shirt—denied undermining May and threatening to resign unless she adopted his Brexit strategy.

Johnson and May were in New York for the United Nations General Assembly but they were also locked in their own diplomatic standoff. Johnson was forced to admit on camera that they had not yet spoken to each other on the trip even though they were staying in the same Midtown hotel.

A détente was eventually declared after several days of what has been generously described as “shuttle diplomacy” by May Chief of Staff Gavin Barwell, who must have been running back and forth between the rival camps like a messenger boy hearing “Well, tell her I said that’s not good enough.”

The latest conflict between May and Johnson began Saturday when the foreign secretary published a 4,200-word dissertation on how to deliver a positive Brexit. The unsanctioned manifesto was seemingly designed to undercut May’s own major speech on Brexit that will be given in the Tuscan capital, which was chosen because of the city’s great history of global trade, not political intrigue.

Johnson’s Brexit doctrine was splashed on the front page of The Telegraph and accompanied by several pages of admiring coverage in the Conservative Party’s house newspaper, including an op-ed by the former editor who declared: “Mrs. May promised us ‘strong and stable’ leadership. It was not to be.”

Johnson professes innocence but this was a clear challenge to May’s authority. He demanded that Britain fully extricate itself from the European single market and refuse to agree to make payments into the Brussels coffers beyond the end of a two-year transition period.

This Brexit campaign leader was stirring up the party’s foot soldiers who doubt that May—who campaigned to Remain in the EU—has the gumption to deliver Britain’s destiny.

Ken Clarke, the party elder and former member of Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet, put Johnson’s gambit into context: “He knows perfectly well that normally a foreign secretary would be sacked instantly for doing that, but she unfortunately—after the general election—is not in the position to easily sack him.”

May’s tenuous grip on the leadership is being played out via the near-impossible task of negotiating a Brexit that will cause least damage to the British economy. Johnson’s bullish demands on one side of the debate are being countered with equal ferocity behind the scenes by Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, who wants a more conciliatory approach that retains many trade and economic features of current EU membership. David Davis, the Brexit minister, continues to bark about the simplicity of Britain’s transformation into a global trading colossus.

All four of them will travel to Florence together in what is laughably being billed as a show of unity.

The wording of the Brexit speech was to be agreed upon at a Cabinet meeting in London on Thursday. Even the chief whip—the keeper of the party line—quipped on Instagram “Cabinet about to start… I am sure it will be quite an interesting one.”

It is reported that Johnson has agreed to go along with the speech after some tweaks had been made, but it remains to be seen how long he can stay on message.

He has struggled to do so throughout his tenure as foreign secretary. It may be no coincidence that his verbose intervention on the question of Brexit strategy followed a stinging critique in The Times, which laid out all of the reasons why “Our foreign secretary is an international joke.”

It was claimed that Johnson had infuriated French President Emmanuel Macron by publicizing Libya peace talks that he had been specifically asked to keep secret. One minister told The Times’ Rachel Sylvester: “It’s worse in Europe. There is not a single foreign minister there who takes him seriously. They think he’s a clown who can never resist a gag.”

She also went on to ask why the foreign secretary had made no meaningful contribution to the Brexit debate despite his key role in winning the referendum.

Apparently it wasn’t a remark Johnson could let slide, even if that meant further destabilizing the government. “So I contributed a small article to the pages of The Telegraph, and now everyone who had previously accused me of saying too little are now saying I am saying rather too much. People have got to make up their minds. What do they want? What I want from my critics is some bloody consistency, the great inveterate jalopies,” he said.

The faux-naivety isn’t going to wash; the latest tangle could be described as his third overt bid for the leadership in just two years.

His first attempt to appeal to the party members—who will probably vote on the next Conservative leader—was to join the Brexit campaign, which pitted him against his then-boss and former school friend David Cameron. Like most observers, he was confident that Britain would vote to remain in the European Union. He knew Cameron would be wounded by the campaign and hoped that a failed but valiant effort would boost support among the grassroots, making him favorite when Cameron chose to step down.

His plan was thrown off course by the shock Brexit referendum result and Cameron’s immediate resignation. Undeterred, he swiftly mounted challenge No. 2; amassing the support of 100 Conservative MPs to select him as the next PM before his old chum Michael Gove turned on him at the last moment, publicly declaring that he was unfit to lead.

That paved the way for consensus candidate May to take over last year. Johnson’s apparent focus is now on ousting her from the job after less than two years—and taking what he sees as his rightful place in No. 10.