In the festival’s 18-year history, it’s something the Tribeca Film Festival programmers and planners have never had to consider. The awards ceremony and most of the events thrown for filmmakers are typically sponsored by liquor companies, and are 21-and-over. This year, however, one of their marquee competitors is underage. “We were like, hmm, do you think he has a fake ID?” one of the festival’s programmers joked to me. “Obviously, we did not ask him that.”

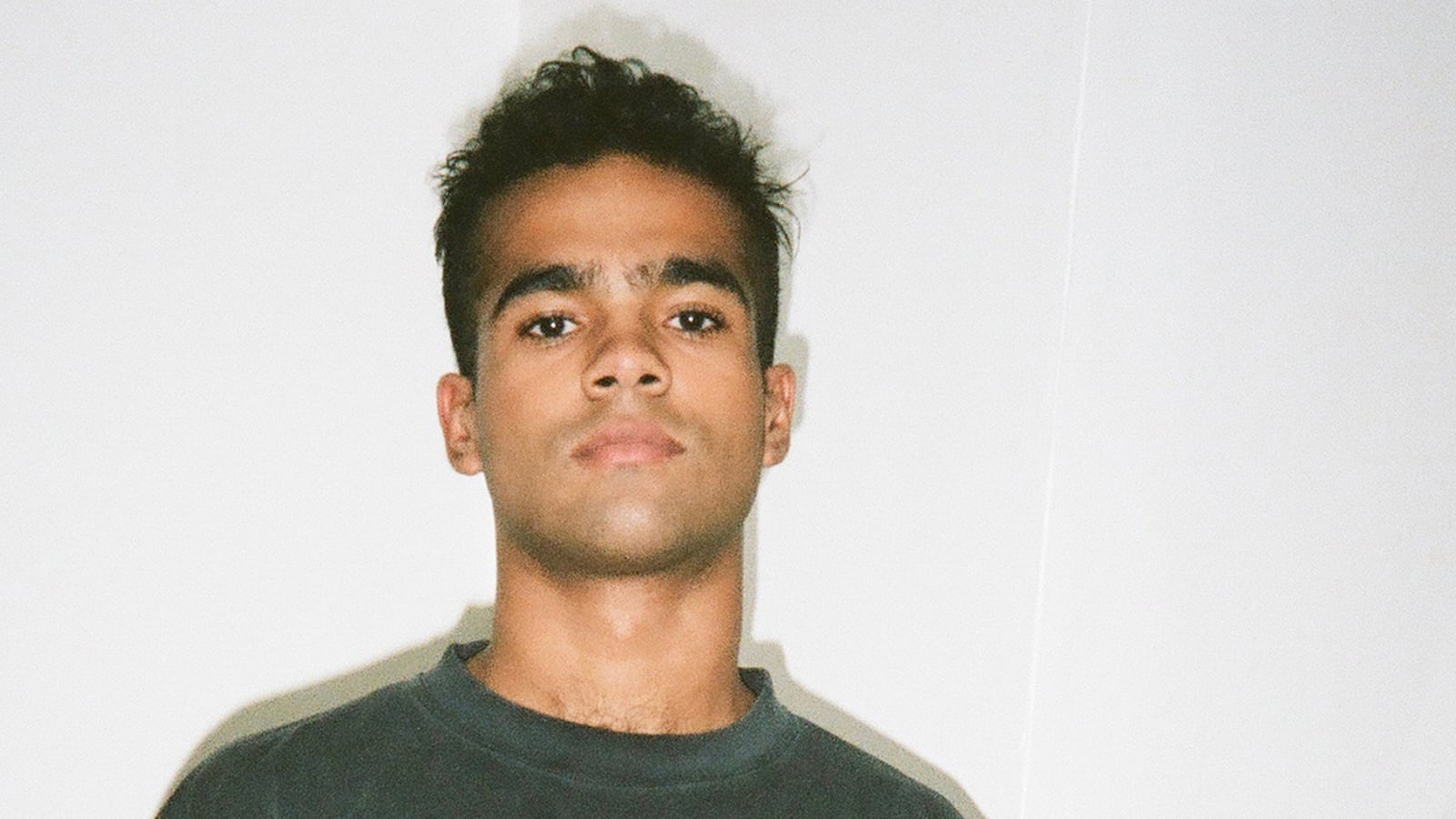

It’s not entirely out of the question. Phillip Youmans, whose film Burning Cane premieres at the festival Thursday, is a freshman at New York University. At 19, he is the youngest filmmaker ever accepted to compete in the Tribeca Film Festival.

He wrote and directed the film, which will vie for the Founders Award in the U.S. Narrative Competition. In recent years, the section included critically hailed indies like Reed Morano’s Meadowland, Ingrid Jungermann’s Women Who Kill, and Nia DaCosta’s Little Woods, which opened in theaters last weekend.

In what would become the repeated choreography and chorus of our conversation when we meet, he shakes his head in disbelief, squirms in his seat, and flashes his broad, youthful smile when I ask how he feels about it all. “It’s so dope, dude.” He runs his fingers through his hair. “It’s totally surreal.”

I’m only the second member of the press he’s ever talked to. When we finish our interview, he has to head back downtown to the NYU campus. He has a Writing the Essay class at 5 p.m., followed by Storytelling Strategies after that. At some point, he needs to study, too.

The festival ends May 5. If Youmans happens to win a prize, the celebration will be brief. There’s only a week left in the semester after that. From Tribeca, he’ll head into freshman year finals.

Youmans is part of an impressive Tribeca class. It’s the most inclusive slate of directors in the festival’s history. Forty percent of the festival’s 103 features are directed by women, and 50 percent of the competition films are. Almost 30 percent are directed by people of color, and nearly 15 percent by people who identify as LGBTQIA.

Even with esteemed filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola, Werner Herzog, and Rob Reiner taking part in this year’s festival, it’s Youmans whose name keeps coming up as one of the biggest draws. At a press luncheon celebrating the opening of this year’s program, Jane Rosenthal, who co-founded the festival in 2002 with Robert DeNiro, singled out Burning Cane as the competition film everyone in attendance should see.

After Youmans was accepted into this year’s lineup, Rosenthal invited him to a meeting at her office. Like any proper film school student—or, let’s face it, 19-year-old male in their freshman year at college—the walls at Youmans’ dorm room in the East Village are wallpapered with the posters for Taxi Driver and Goodfellas. DeNiro and Martin Scorsese will be interviewing each other at a special event at the festival, and Rosenthal promised that she’d introduce Youmans to them. She even sent Scorsese a screening link to his film.

She promised an intro to Francis Ford Coppola at a screening of a new cut of Apocalypse Now, too. “It’s so insane,” he says, beaming.

Youmans grew up in New Orleans’ Seventh Ward. “If you start in the French Quarter and go up towards the lake, it’s around there,” he says. He and his sister were raised by his mother, who transplanted to New Orleans from Lowcountry South Carolina. He went to a French immersion elementary school, and then high school at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts.

At around 12 years old, he started taking acting classes, and eventually started auditioning for and booking small roles in projects that shot locally around New Orleans. He was an extra in 2014’s Sex Ed, starring Haley Joel Osment, and had a small speaking role in 2015’s American Hero. On set, he found himself more interested in the conversations that the director and the DP were having than where his mark was supposed to be. From that point on, at age 14, he began making his own shorts.

His upbringing was rooted in the Baptist church, which inspired Burning Cane. His mother would take him every Sunday. During summers at his grandmother’s house in South Carolina, where she was the accountant at her town’s church, he would go almost every day.

Burning Cane is set in rural Louisiana, where cane fields backdrop the devastating tension between religion and family as an aging mother contends with her values and a grown son whose alcoholism and vices are overtaking his life. Wendell Pierce (The Wire) plays her conflicted preacher, a commandeering and leading presence in the community, but whose own alcoholism consumes him.

“I knew I wanted to touch on a lot of conversations and debates I was having within myself in the church and stuff that I had kind of always been going back and forth about throughout my whole upbringing,” Youmans says. “I’ve always been able to recognize why it’s powerful in terms of community building, but I’ve also always been able to realize that there’s a lot about the doctrine and what’s being preached that doesn’t speak to the sentiment of a lot of people who are attending church. A lot of it can be destructive.”

Burning Cane began as a short film, titled The Glory, that Youmans began writing when he was 16. Encouraged by one of his teachers, he started writing a feature version of the story. He shot the film near his arts school when he was 17. He edited it when he was 18, and finished the summer after he graduated, a month before heading to NYU.

He started an IndieGogo fundraiser to fund production, supplementing costs with his savings and money he made working at a beignet stand. His mother also donated money to the cause. But things really changed once he caught the attention of Oscar-nominated director Benh Zeitlin (Beasts of the Southern Wild), who would eventually become an executive producer.

After wrapping principal photography, Youmans cut a miniature trailer and sent it via direct message on Instagram to Zeitlin, who had an arts non-profit called Court 13 Arts that included a mentorship program for young filmmakers—but whom Youmans didn’t know personally.

By a miracle, Zeitlin watched it, and was immediately taken with it. He took Youmans under his wing, helped him secure a cash grant that would allow him to license music and set him up with an editing suite, where they would sit for hours together combing through the footage.

Zeitlin had no idea how young Youmans was when he watched the video he had sent over Instagram.

“What’s amazing both for his age, but for anybody, is that his work is totally not derivative of anything,” Zeitlin says. “Especially for someone coming up that young, you meet lots of filmmakers who are huge film fans and want to be Quentin Tarantino or want to be Martin Scorsese, but Phillip is drawing his own vernacular that seems to come from him completely magically.”

He was struck not only by Youmans’ raw talent, but how he engaged with the world.

“There’s a complete fluidity between his questions about film and his questions about, like, life,” he says. One question will be about whether a voiceover works in a particular scene, closely followed by whether Zeitlin thinks love lasts. “I think it’s emblematic of someone whose life and the way they express themselves with art are inextricably connected.”

Youmans submitted a five-minute version of Burning Cane, a character study called The Reverend that focused on Pierce’s character, with all of his film school applications. Ultimately he chose NYU because of a lifelong calling he felt to New York City.

He was in a recitation for a psych class when he checked his phone and saw the email that he had gotten into the Tribeca Film Festival. He ran to the bathroom and called his mother and texted Pierce. Then—he laughs even just remembering it—he had to go to back to class.

A question about what he does for fun as a freshman at NYU quickly turns to talk about more work—and some unintentional name dropping. He’s not much of a partier, he says. He’s been to one party, but it wasn’t in a dorm. “It was actually a frat party,” he says, laughing. “Maybe that’s why.”

He spends most of his free time working on extra-curricular film projects. He’s in post-production on his first short doc in collaboration with musician Jon Batiste, and also for a short narrative film he’s making for Solange’s brand, Saint Heron.

“It’s dope. Dude, it’s crazy,” Youmans marvels over the fact that he is even mentioning the name Solange in our interview. “I really dig how unapologetically black everything she does is. I just feel fortunate really to have even fell into that situation, because I feel like it really aligns with my vision to tell black stories.”

Zeitlin isn’t surprised that the young filmmaker is finding so much success already. There’s something about the way he thinks that feels both fresh and familiar.

“It’s innovative, but it feels ancient,” Zeitlin says. “It’s not hip, it’s not new, it’s not flashy. It’s at the core of something that is eternal. It’s almost like when you listen to folk music and it’s the same song you’ve heard how many thousands of times, but the way someone plays that song makes it new again. That’s how Phillip’s film seems to me: I know this, but I’ve never seen this.”

A contingent of Youmans estimated to be around 15 strong will join him for Burning Cane’s premiere Thursday. His grandfather, who is also named Phillip Youmans, is particularly excited to see the moniker flashed in the credits of a film playing in a New York City movie theater.

Then again, the shake of the head, the fidgeting, the big sigh and bigger smile: “It so tight, man. Really. It’s insane.”