Is there any other nation on earth so enamored with the idea of a funny chief executive? Ingrained in our anti-monarchistic democracy is a populist pleasure in hearing our presidents make self-deprecating jokes, while comedically jousting with political foes. What else would explain why every spring since 1920 (the year of the first White House Correspondents Association dinner) we have asked our president to deliver a comedy routine instead of, say, recite poems, perform an interpretive dance, or juggle objects of various shapes, sizes, and weights. Even our last president, George W. Bush, managed to oblige our need for presidential humor, exceeding expectations with some playful single entendres.

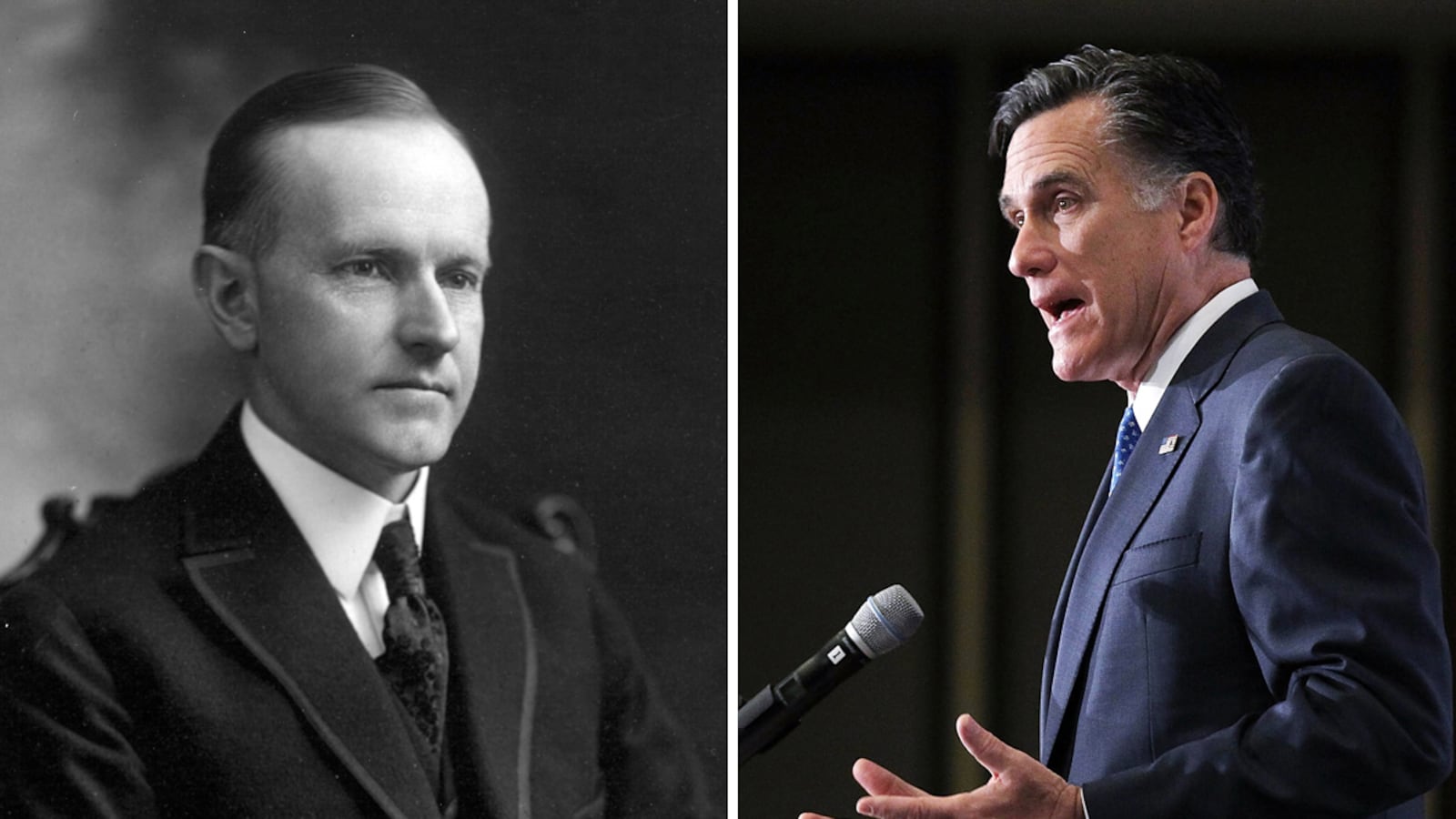

Accordingly, presidential historians are prone to rank our chief executives by their sense of humor, assembling a Mt. Rushmore of sorts of stand-up standouts. Not surprisingly, Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan almost always top the list. But on this President’s Day of this presidential election year, allow me to nominate another candidate to join the pantheon of funny presidents and explain how his alternative style of humor could be instructive to the current crop of would-be commanders-in-chief. Ladies and gentlemen, please put your hands together for our 30th President of the United States, “Silent Cal” Coolidge!

Nestled between Warren Harding and Herbert Hoover, Calvin Coolidge survives today as one of the many animatrons in Disneyworld’s Hall of Presidents with a non-speaking part. This would have been his strong preference; like the silent movie stars of his day, Coolidge earned his laughter by way of restraint. Rather than be saddled with a comic persona foisted upon him by others, Coolidge fostered his own: a lackadaisical loafer largely disinterested in his own presidency. It was a high-wire act to be sure, but Calvin Coolidge managed to pull it off.

Coolidge was elected vice president in 1920 and became America’s sixth substitute president when his boss, Warren Harding, died in office. Cal’s interest in the job appeared half-hearted from the moment he was sworn in. His first act as president was going back to bed.

Later in his presidency, a reporter asked him if he had any hobbies. To which he responded: “I hold office.”

His renowned reticence earned him the nickname “Silent Cal,” and one Washington socialite—the daughter of Teddy Roosevelt, no less—famously described him as a man who appeared to have been “weened on a pickle.” At a dinner party, the woman next to Cal tried to engage in conversation by bringing up a bet she had made. She had bet, she told the reticent president, that she could get more than two words out of him. Coolidge’s response: “You lose.”

Coolidge not only insisted on sleeping 12 hours every night; he seemed determined to make that fact well known. During the day, he almost always got in a two-hour nap. What was his explanation? When you’re asleep, you can’t make any bad decisions! Upon waking up, he would reportedly ask his aide, “Is the country still there?” With jokes simultaneously anti-government and self-deprecating, Coolidge invented the presidential brand of humor that Ronald Reagan would later make his signature. Indeed, Coolidge’s fundamental conservatism was well-expressed in jokes like these, as they arose from the idea that America does not need a president—or a government—to be great. Sounds like a Tenth Amendment guy to me!

No matter his ideology, Coolidge arrived at an insight that today’s political consultants charge hundreds of thousands of dollars to dispense: voters crave authenticity. The American public of the 1920’s rewarded Coolidge with their genuine affection, and had he run for re-election in 1928, conventional wisdom decrees that he would have likely won. Instead he announced “I do not choose to run,” which was a line so memorably peculiar that decades later, none other than the namesake of Seinfeld paid it homage in a well-loved episode.

But what is the point of history if not to learn its lessons, and perhaps there’s a valuable one for another former Republican Massachusetts governor. Mitt Romney’s stabs at humor come mostly in the form of one-liners too-obviously culled by his staff and spelled out phonetically into the margins of his remarks.

But if you listen carefully, you can hear Silent Cal whispering another way. The problem Mitt Romney has connecting with the other 75 percent of his own Republican party is that he appears reluctant to let his true self be known. Perhaps because of his famously secretive religion, or the fact that he signed a thousand too many non-disclosure agreements from his days at Bain, Romney is the candidate incapable of candor. Is it any wonder that voters are wary of a person so obviously afraid of his own thoughts? Romney would do better to let himself be known or, more to the point, create a more plausible persona that resonates with truth and then have some fun with the results! Is he stingy? Does he love puzzles and board games? Is he lactose-intolerant? Or is he just a straight-as-an-arrow Eagle Scout, far more Clark Kent than Superman? OK, that can work too. Remember: Al Gore spent the better part of his vice presidency telling anyone who would listen that he was stiff and boring to brilliant effect, coming within one Scalia of becoming president.

As Mitt Romney flies around the country in his bid to be as beloved as Lincoln—espousing his (new-found) love for Ronald Reagan and spitting out JFK-style bon mots that are just not that bon—he would do well to emulate the authenticity of Calvin Coolidge and a brand of humor that is true to self, whatever that self may be.

Listen up, Mitt: Silent Cal is trying to tell you something.