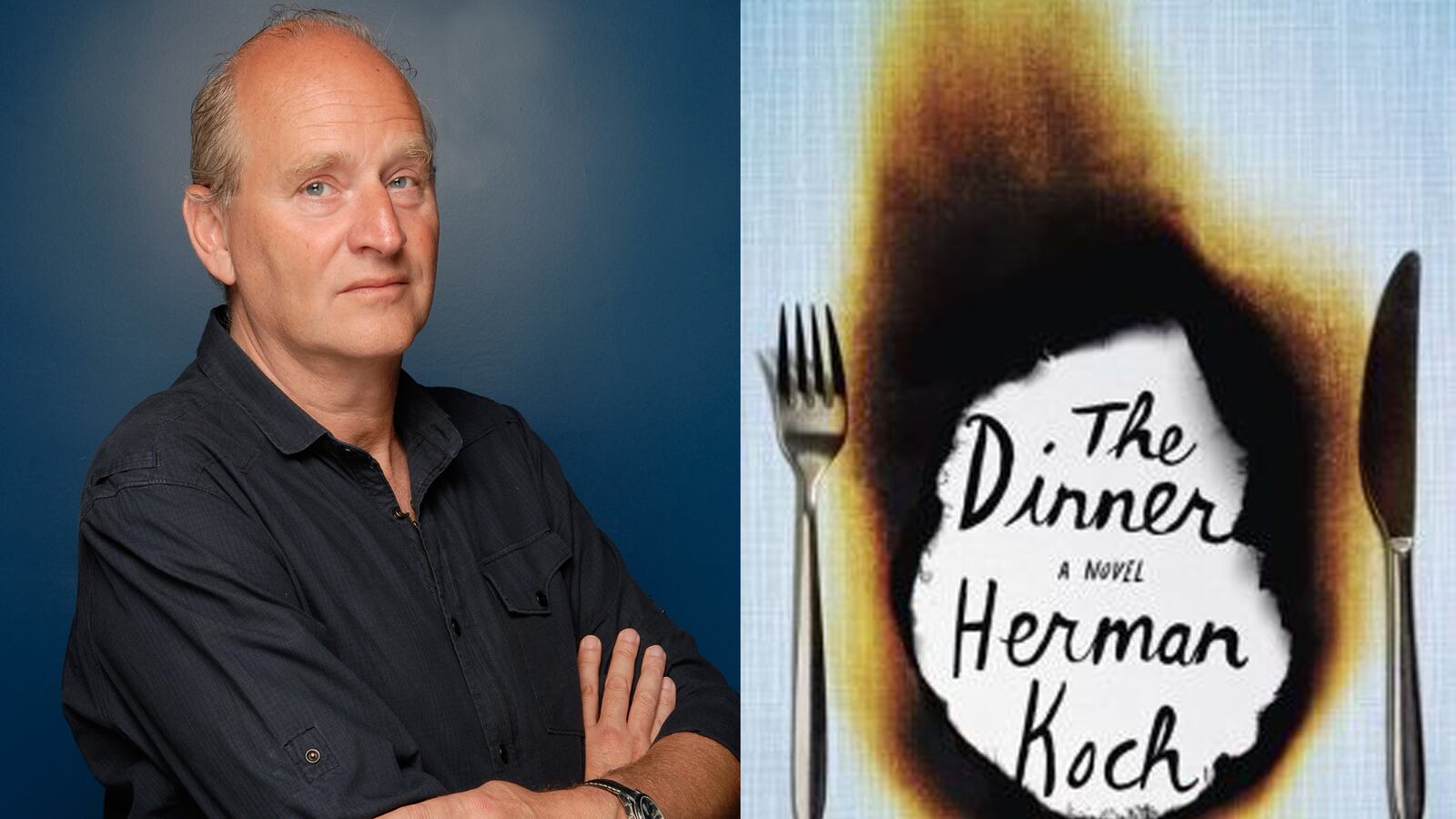

When Herman Koch’s The Dinner is released in the United States this week, it will have already sold well over a million copies. It will have already become a bona fide publishing phenomenon and a topic of spirited cocktail conversation. This is because it will have already been published in 15 other countries, with release in eight more on the way.

The question now: can this Dutch literary sensation strike a chord in America as well? The Dinner has already surpassed perhaps the biggest barrier to success in the American market—finding a publisher. Commercial houses here are notoriously averse to taking on translations. Independent presses take more chances, but conventional wisdom holds that about 3 percent of all titles are translations, and less than 1 percent of trade fictions are. (Editors I spoke to refer to the blog Three Percent as the most thorough and reliable source on the matter.)

The language barrier is an obvious culprit. “So few editors [in the U.S.] read in second languages or third languages,” says Michael Reynolds, the editor in chief of Europa Editions, an independent publisher focused on bringing foreign fiction to America. While all of Reynolds’s editors read in at least one other language, in most cases U.S. editors rely on less direct means of vetting foreign works. “A lot of finding interesting international books is about the collective mass of enthusiasm from people we know and whose taste we tend to trust,” says Amy Hundley, an editor at Grove/Atlantic, an imprint with a history of embracing foreign fiction. Hundley also points out that foreign agents increasingly commission sample English translations to help sell their books in other countries.

In the case of The Dinner, a translation had already been completed for publication in the U.K. by the time the work went up for auction with U.S. publishers. Hogarth Press, a division of Random House launched in 2012 with an eye toward literature with international appeal, ultimately beat out six other bidders for the novel.

Hogarth now hopes The Dinner will join the exclusive list of international phenomena that found success in the U.S. Sweden’s Stieg Larsson and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo provide a high-profile example. But more ardently literary works have broken through as well—Roberto Bolaño’s catalog, for example, or, most recently, Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard’s autobiographical work My Struggle.

From these authors, though, it can be a steep drop to one like Jonathan Littell, whose 2006 French novel The Kindly Ones became a critical and commercial smash in that country, and came to the U.S. three years later with bloated expectations. The reaction here, though, was often scathing—Michiko Kakutani slammed the novel in The New York Times, for example—and it ultimately proved a $1 million blunder for Harper, selling only 37,000 copies to date, according to Nielsen BookScan, which tracks 85 percent of the print book market.

The most encouraging precedent to The Dinner may be The Elegance of the Hedgehog, the 2006 French novel by Muriel Barbery published in the U.S. by Europa Editions in 2008. Like The Dinner, it’s a highly readable story set in a European capital, using personal struggles to illuminate greater societal and philosophical concerns. To date, it has sold 750,000 copies here, according to Nielsen BookScan.

Hedgehog turned out to possess a crucial universal appeal. A foreign translation “needs to have that ability to cross borders, to speak to a larger audience versus a regional one,” says Corinna Barsan, another editor at Grove/Atlantic. The Dinner’s American editor, Alexis Washam, believes Koch’s novel possesses this X factor. “There are moral and ethical problems [in the book] that could take place in any culture,” she says. That it has found audiences from Turkey to China to Australia would suggest she may be right.

Its prospects are at least partly driven by the story, of course. And The Dinner’s plot is a compelling one, unfolding over—you guessed it—dinner, in this case one shared by two brothers and their wives in a chic restaurant. Their meeting, it soon becomes clear, is precipitated by a dire turn of events involving their sons. Given the framing of the story, with each section representing a dinner course (opening with “The Aperitif,” for example), the pages could easily have descended into gimmickry. But Koch’s ability to toy with the reader’s alliances while using one family’s distress to consider greater societal ills gives the novel a vital punch.

A final hurdle may lie simply in getting the word out. The Dinner’s publicists got lucky again with Koch—he is fluent in English and schooled in American culture, making interviews and appearances a relative cinch. Ahead of The Dinner’s U.S. publication, Koch came over to meet with media and booksellers. That effort paid off with NPR, which is airing an interview on Morning Edition and has published an excerpt online.

But generally speaking, publicists continue to fight the lingering sense that foreign fiction is not palatable for the general reader. “There’s still a perception that translated books are ‘small’ … Part of that has to do with what has traditionally been translated,” says Hundley. “Difficult literature that is gunning for the Nobel Prize isn’t necessarily going to reach the audience of a Stieg Larsson.” But Hundley believes the situation is improving. “Literary fiction in translation that sells is no longer considered an oxymoron.”

Ultimately, American readers may be more enthusiastic about foreign fiction than they’re often given credit for. “Having a list that’s filled with perspectives that are different from the American one is actually finding a larger American audience than might have previously been thought,” Washam says. Michael Reynolds agrees that for literary readers, the country of origin isn’t a hurdle at all: “I find that American readers don’t care whether a work is a translation or not. I think they’re interested if a work is good or not.”