ROME—If there is one open secret in the eternal city, it is that the allegations of clerical sex abuse in Italy have always been swept away, into the shadows of the Vatican.

The last three popes have had mixed reviews on their handling of the global scandal. When the worst of the abuse was coming to light, Pope John Paul II was too infirm and impotent to do anything about it. His successor Pope Benedict XVI was demonstrably blind to the problems coming in from the global church, and was implicated in the coverup in Germany. Pope Francis has done more than both of his predecessors in terms of reconciling the pain. But none of these leaders of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics have done enough or what the victims want, which is that clerical child sex abusers are treated like secular ones: that they go straight to jail.

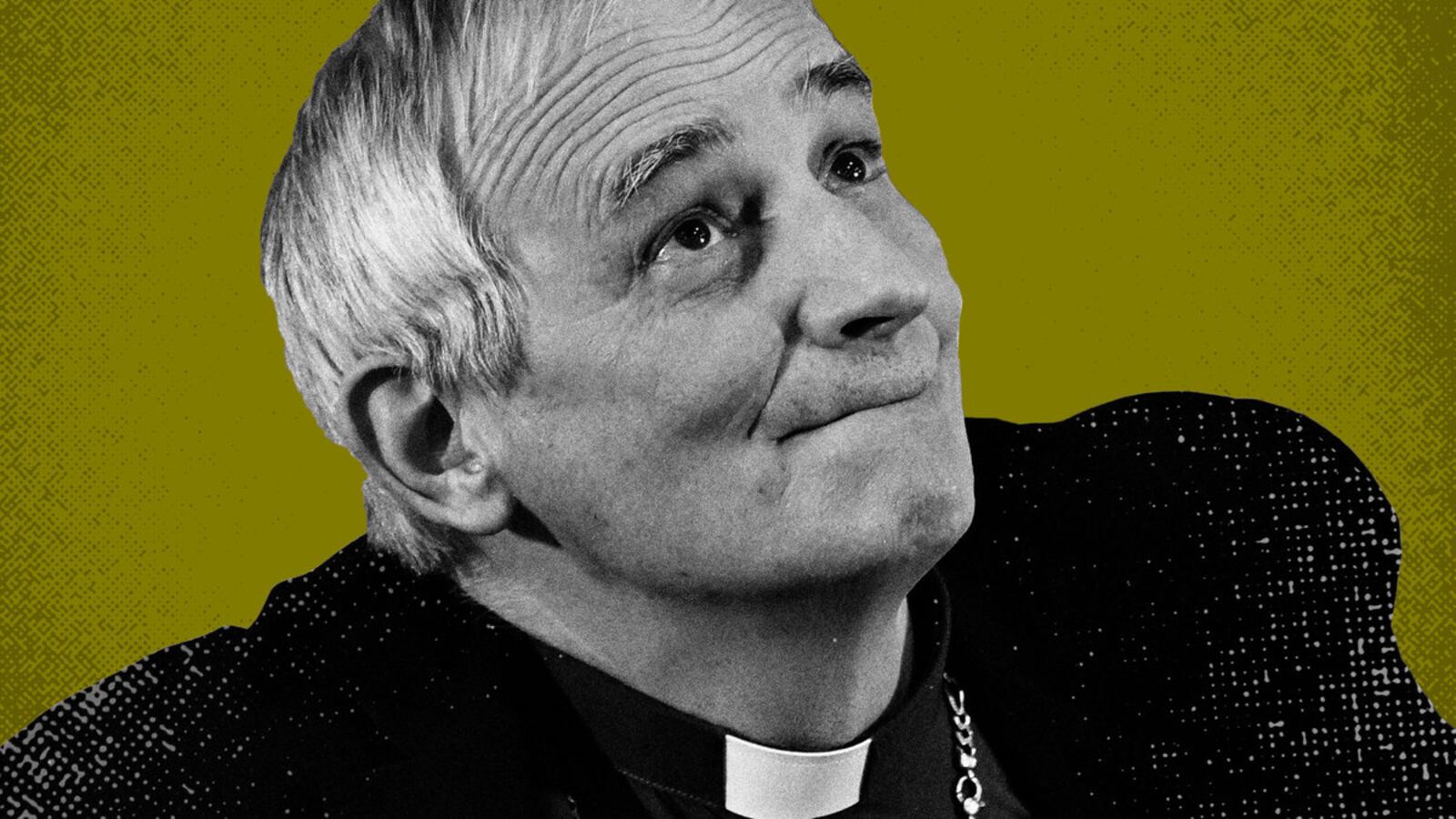

The idea that rampant abuse that has been exposed in the United States, Germany, Ireland, and elsewhere is also happening under the popes’ noses in Italy for decades has been something previous pontiffs have successfully kept a lid on. But an increasing drum beat from Italian sex abuse victims has sent a shockwave that has finally reached the Holy See. And the new head of the Italian Bishops’ Conference, Cardinal Matteo Maria Zuppi, has just promised to break Italy’s so-far hidden sex abuse history wide open by implying that the seat of the Roman Catholic Church is directly involved in covering up the crimes in its host country. He says he will investigate what has until now been no-go territory, guarded by church insiders who were in some ways as powerful, influential, and dangerous as the mafia.

If Zuppi makes good on his laundry list of promises—including having academics aid in researching complaints that might have been buried in the Vatican archives, looking at ignored police reports, and listening to the until-now-stifled accusations of Italian victims—the Vatican will patrol its own backyard effectively for the first time since its special city state status was signed off by Benito Mussolini.. Any investigation of any regional Catholic church ends up on the pope’s desk in Vatican City. And Zuppi has promised not to hold back. “No coverup, no resistance from the bishops. We will take the beating we have to take and also our responsibility,” Zuppi said as he accepted the papal appointment. “We owe it to the victims; their pain is the priority. And we owe it to the Holy Mother Church.”

Zuppi said that on Nov. 18, the Vatican will publish its analysis of all the complaints of clerical sex abuse in Italy—something that has never been attempted given the Catholic Church’s mafia-style influence across the country. Every city in Italy has a patron saint, bank holidays are primarily holy days, and priests play God in almost every single community. Survivors say reports of abuse have always been snuffed out and “taken care of” by shuttling the predator elsewhere or, as is often the case, straight to Vatican City for a little penance.

Francesco Zanardi, a vocal survivor from the northern Italian town of Savona, started publishing accounts of abuse in a newsletter sent out widely from his support group Rete L’Abuso, or Abuse Network. His social media has gone viral with his hashtag #ItalyChurchToo which, in its one year of existence, has pulled back the curtain on grotesque accounts at the hands of influential church members in this hyper-religious country. He says he hopes that Zuppi’s investigation will truly do what it promises, and that the usual “interference“ by the Italian Catholic hierarchy over the Italian judicial system won’t make it impossible. He told The Daily Beast that the very fact that crucifixes hang by law in all Italian courtrooms is more about “omerta” than faith. He says they are there as “a threat and reminder that the Church is more powerful than even God.”

Zuppi’s predecessor, Cardinal Gualtiero Bassetti was pressured by many in secular society to heed the calls of Zanardi’s growing influence to launch an internal investigation of the magnitude of Pennsylvania’s in 2018 that found more than 300 predator priests and 1,000 victims in that state alone.

When Zuppi made the announcement at his swearing-in over the weekend, the 223 Italian bishops were told that they would play a very big role in self-policing, which has not been a particular strength among any of the Catholic hierarchy. Italy currently does not have “listening centers” or safe lines to call to report abuse in 30 percent of the country, which is 90 percent Catholic.

The first phase of the report will focus on the years between 2000 and 2021, a period when predator priests were finally put in check in other countries by increased involvement from the secular judicial system. But in Italy those years could prove horrific since no one was investigating reports. It remains to be seen how bad the abuse allegations are from the decades before.

Zuppi did say that the “Italian path” would differ from countries that recently blew the lid on their sex abuse scandals, including Germany, France, and Spain. In Italy, he said the plan would not be merely “lip service” or a “false acknowledgement” of the problem. “The investigation will be a serious, real thing that leaves no room for controversy,” he said, nodding to France’s report that is still being debated among the French Catholic hierarchy. “We don’t want to argue, we don’t want to sidetrack. The report does not serve as a sedative, but to do things seriously.”

The reason Zuppi said he would focus on the previous 21 years first is because it is more relevant. “With regard to the past 20 years, it has to do with us, it involves us directly. It feels much more serious to us, it hurts much more,” he said. “1945 was 80 years ago. I believe that judging something from 80 years ago by today’s criteria, something that was judged by other criteria at the time, creates difficulties of evaluation.”

Zanardi, who says he knows of 1,600 cases from before 2000, says instead that the time limit was discriminatory and it could make the problem seem smaller than it is. Zuppi has asked Zanardi for a meeting. “We would be very happy to meet with you,” he told Zanardi, who attended his first press conference and asked the incoming cardinal about reparations. “If you have a case, tell us. I don’t know if you’ve already done so, I’m speaking only for myself... Then there’s the State, you go to the police. Surely it will be very useful to make a report.”

For years, these accusations have been buried to protect the Vatican and its popes from embarrassment. The task to untangle such a deep web of sinister secrecy is daunting.