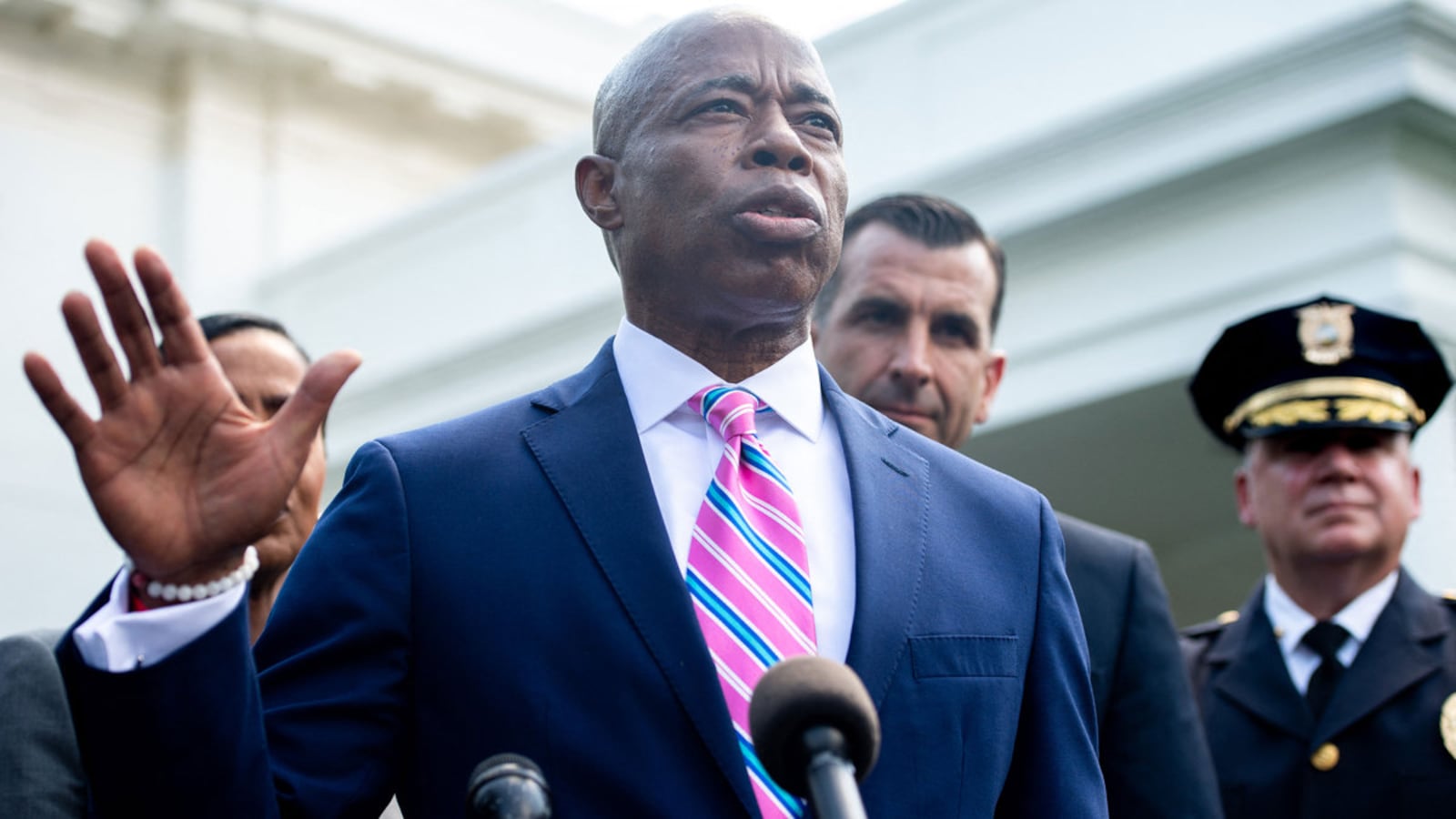

President Joe Biden will meet with New York City Mayor Eric Adams next week to discuss the mayor’s plan to combat gun violence. It’s not their first talk. Last summer, when Adams was a candidate, he met with Biden to discuss crime and they got along so famously that Adams declared, “I feel like I'm the Biden of Brooklyn.”

Both men frame their approach to criminal justice as moderate and pragmatic, balancing reform with public safety—while eschewing both “defund the police” and “tough on crime” postures. Their centrist politics won’t win them many fans among the progressive activist wing of the Democratic Party, but it propelled both men to victory over more radical candidates, in large part thanks to people of color who are the most affected by crime.

The accepted wisdom among the political commentariat held that the winning moderates’ plans are about common sense, and attuned to the dangerous realities of the street—a welcome alternative to the fantasies peddled by radical reformers.

But what if it’s lawmakers like Adams and Biden, with their sensible-sounding centrism, who are the delusional ones, rolling back the clock on crucially-needed reforms they’ve previously claimed to support?

The deadly, nationwide wave of gun violence of 2020 was horrific. But, there are many indicators that point to the now-waning pandemic as the main driver of violent crime.

And new “tough-on-crime” measures that result in a larger population detained pretrial are not likely to lower violent crime long-term: Any entanglement with the criminal justice system destabilizes people’s lives. They might lose a job, be frozen out of professions as varied as EMT and hairdresser, lose public benefits like housing, or even custody of their kids. According to the Bureau of Justice, 67.8 percent of formerly incarcerated people were arrested for a new crime within three years—and research shows that steady employment and strong family ties are the most effective at preventing recidivism.

And since the average prison sentence is roughly five years, most incarcerated people will end up back in the community, carrying the trauma of prison and frozen out of opportunities that would make them less likely to re-offend.

Further, “tough-on-crime” advocates often whitewash the dangers of harsh policing. Adams, who was beaten by officers of the 103rd precinct as a child, has brought awareness to abusive police behavior. But you might not know it from looking at his blueprint for stopping gun crime, to which Biden has pledged “full support.”

The mayor was lauded for vowing to invest in youth programs, but the rest of the plan is one giant roll-back of the modest reforms of the past few years, such as bail reform and the dissolution of controversial plainclothes units, with no clear plan for stemming abuses.

Adams wants to try 16-year-olds who are found with guns in adult court. He wants to let judges gauge “dangerousness” before setting cash bail, a policy likely to further strain the overcrowded war zone that is the jail on Rikers Island (New York City public defenders have extended an invitation to Biden to visit Rikers on his trip next week). Adams also seeks to promote Crime Stoppers, a group that turns anonymous tips over to police and awards cash prizes to informants.

Distressingly, the mayor, a former NYPD captain, is fast-tracking the relaunch of the plainclothes units that had been disbanded by former Police Commissioner Dermot Shea in 2020 after decades of misconduct.

The plainclothes units, composed of officers dressed in civilian attire to avoid detection, were the forces behind some of the very high-profile killings that helped spark the Black Lives Movement movement: Eric Garner (killed by police in 2014 after being suspected of selling loose cigarettes), Sean Bell (killed on the morning of his wedding in a hail of 50 bullets), Amadou Diallo (killed by police in 1999 while standing on his front stoop and reaching for his wallet).

Additionally, the plainclothes units cost the city millions in lawsuit payouts for excessive force, assault, false arrests, framing people for gun possession, and racist stop-and-frisks.

Citing his own experience, the mayor has sternly declared that he’s going to hold bad cops accountable. But when pressed on details, he cited body-worn cameras, which studies have shown don’t significantly change officer behavior or lead to accountability. While a bodywork camera—when properly turned on, not obscured, and whose footage doesn’t get buried in the NYPD vaults—might lead to accountability in a clear-cut case, many forms of alleged abuse are much harder to document from body cams alone.

An even less-practical idea cited by Adams was having such units wear special windbreakers that identify them as cops. This presents the obvious conundrum of a supposedly undetectable unit essentially wearing a uniform—in this case, a windbreaker jacket that would be particularly conspicuous in New York’s summer heat.

Adams also stressed that officers would undergo rigorous training and be strictly vetted based on their personality type and disciplinary records. “You must have the right training, the right mindset, the right disposition and be, as I say all the time, emotionally intelligent enough that you are getting ready to engage someone in the street,” Adams has said. But this week, the mayor promised to launch the plainclothes units during the next three weeks, a rather thin timeline in which to do all the necessary vetting and training.

One thing that’s absolutely clear is the street crime units’ directive: they are to focus on getting guns off the street. But that also presents a potential problem. Last year, uniformed NYPD officers confiscated a record number of guns: 6,000. That’s more guns than at any time since the 1990s. Naturally, the pressure will be on the plainclothes units to match or top that number—otherwise, why risk bringing back a unit with such a troubled history and bad reputation?

And part of that troubled history stems from police abuses that occur when officers are under the gun, as it were, to produce results.

Data-driven policing, like COMSTAT, has had the perverse result of pressuring officers to make more arrests to generate favorable numbers. The racist use of stop-and-frisk is among the common examples of abuse. But there have been multiple incidents of NYPD officers trampling the rights of civilians in order to rack up collars, from interrogating innocent people until they cough up information to brazenly planting weapons on suspects.

To cite one example, in 2014 officers framed three men for gun possession. The tips that led officers to the innocent men were processed by Crime Stoppers, the group also promoted in Adams’ blueprint. Advocates have suspected that police themselves called in the fake tips. Two of the men falsely arrested spent a year locked up at Rikers.

To recap, Adams is fast-tracking the mobilization of a historically dangerous unit, which has a fraught relationship with the community, which is now tasked with the mission of saving the city from deadly violence, and whose failure to do so would likely sink Adams’ mayoralty. But, surely, they won’t bend the rules to get results, since they’ll have cameras and windbreakers?

Adams is not the only practitioner of magical thinking posing as reasonable centrism. The Eric Adams of Washington, President Biden, recently earmarked millions in funding to police, with no caveats on how it’s to be used.

“We shouldn’t be cutting funding for police departments. I proposed increasing funding,” Biden said to a conference of mayors. The president is funneling $651 million in his 2022 budget to expand hiring in police departments, and there’s also $350 billion in discretionary funds from the 2021 American Rescue Plan—a COVID-19 relief initiative—to expand police budgets, anthropologist Eric Reinhart reported in Slate.

Why does Biden think that, this time around, federal and local incentives that spur more aggressive policing will solve crime, without leading to widespread misconduct and mass incarceration?

Adams and Biden lived through the “tough-on-crime” sprees of the 1980s and 1990s that turned the U.S. into the top incarceration nation in the world. Biden was one of its primary architects, while Adams was one of its countless victims. The president, while campaigning in 2020, expressed regret for his role in crafting harsh sentencing laws and cruel drug policies. And Adams, as a member of the city council, has been a proponent of police reform.

You’d think they might be less inclined to create policies, laws, and funding streams that would fuel another “tough-on-crime” wave.