NICE, France — Charlotte Salomon, a young German-Jewish painter from Berlin, was among thousands of Jews who fled to one of the few places they felt safe during World War II: this sunny paradise on the Mediterranean.

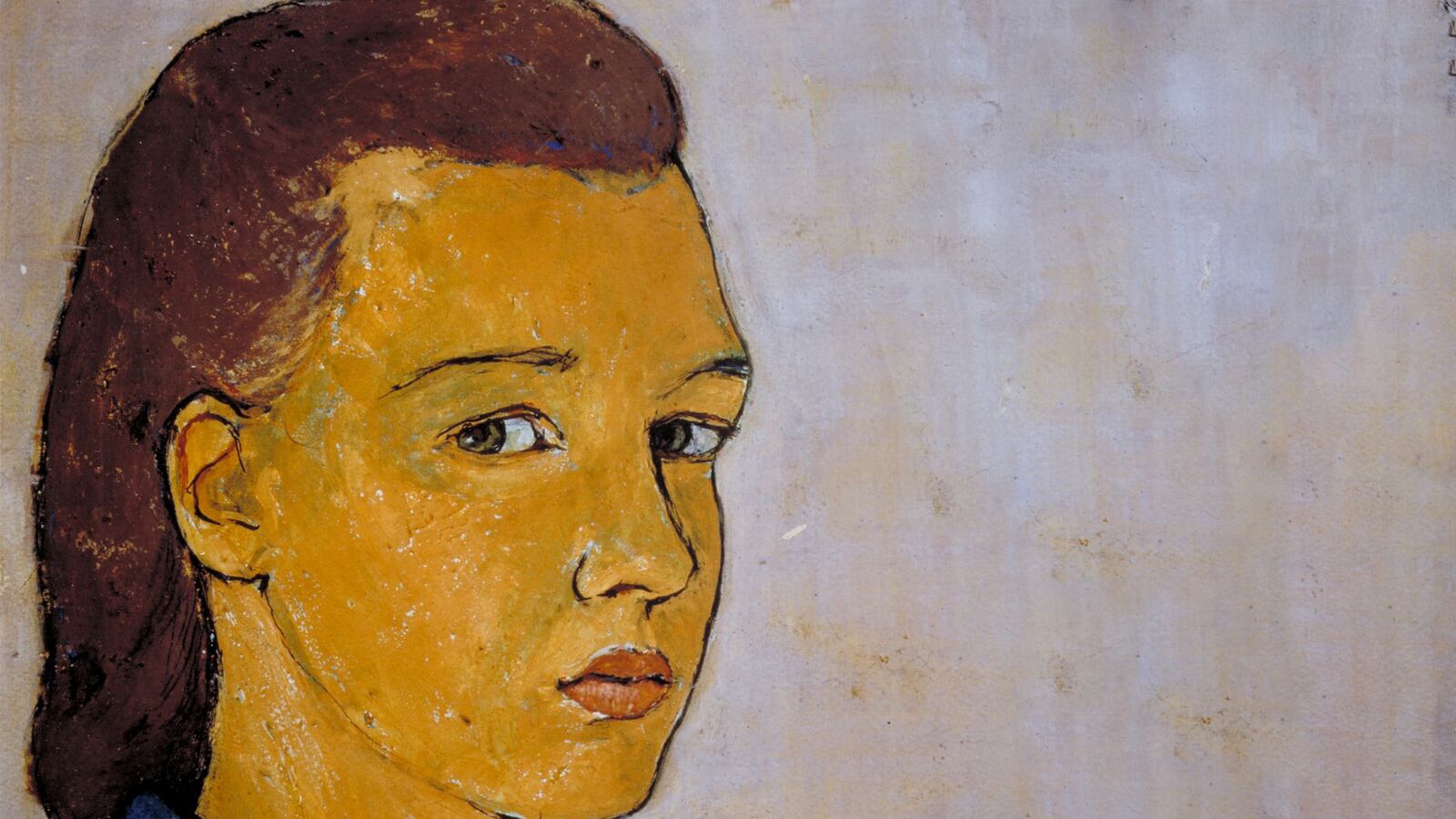

“The war raged on and I sat by the sea and saw deep in the heart of humankind,” Salomon wrote in her masterwork, a one-of-a-kind unperformed operetta consisting of 1,300 colorful paintings overlaid with text called “Life? Or Theater?” produced in a feverish 18-month race against time while she was living on the Cote d’Azur.

“I will create a story so as not to lose my mind,” Salomon wrote in one of her darker passages. But her pessimism was outweighed by her optimism. “How beautiful life is. I believe in life. I shall live for them all.”

The dream of a refuge in the south of France turned nightmarish in September 1943 when the protection given the Jews during the Italian occupation of Nice evaporated after Italy signed an armistice with the Allies. The notorious Austrian-born Alois Brunner, one of the most sadistic and murderous Nazis, quickly showed up here to oversee what one local historian called a “human hunt on the Cote d’Azur.”

Salomon, just 26 and four months pregnant with her first child, was one of Brunner’s first victims. A Gestapo truck picked up her and her husband in a house a few miles outside Nice in Villefranche-sur-mer on Sept. 24, 1943. A housekeeper remembered hearing “screams.” Salomon was gassed at Auschwitz on Oct. 10, 1943.

But unlike Anne Frank, another German Jew whose journal was discovered right after the war and published in 1947, Salomon’s stunning and heartbreaking visual diary has remained relatively obscure despite exhibitions of her work and several films about her life. Were it not for Salomon’s own foresight and the tireless efforts of a few people who labored to preserve and promote her, it might never have come to the public’s attention.

“Keep this safe. It is my whole life,” Salomon said when giving her work to a friend on the Riviera for safekeeping—even though she didn’t know that deportation was imminent.

Salomon has become a new obsession in France thanks to a recent bestselling and prize-winning short book, Charlotte, by French writer David Foenkinos, which will be published in English in the U.S. next month.

Most importantly, for the first time since Salomon was deported from Nice in 1943, "Life? or Theatre?” is finally being shown here through May at the Musée Masséna, and Salomon’s work shines a light on a horrifying era called les années noires, or “black years,” long lost to the touristy, mythic image of the region.

“It’s where she lived and it’s so extraordinarily moving to see it on display there,” said Foenkinos, who became obsessed with Salomon after seeing her work in Paris in 2006.

The exhibit, housed in a museum just blocks from the notorious Excelsior Hotel where 3000 Jews including Salomon were kept before being herded up one block to the train station and transported to concentration camps, is normally at the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam.

"Life? or Theater?" chronicles what it was like to be from a bourgeois family in Berlin during the heady and then chilling final years of the Weimar Republic—and later details the grim reality of being forced to decamp to the south of France where the beauty of the region and perceived safety gave way almost overnight to mass arrests and deportations in 1943.

Not long after the Kristallnacht in 1938, a coordinated attack on Jews throughout the Reich, Salomon was sent to live with her grandparents who had fled to Villefranche-sur-mer in 1934 and were taken under the wing of an American woman named Ottilie Moore who helped refugees.

It was there where Salomon discovered she came from a family with a history of suicides. When she was nine she had been told her mother died of pneumonia, but in fact her mother had killed herslef. Her aunt drowned herself. Her grandmother jumped out of an apartment building in Nice not long after Salomon arrived in the south of France.

“It would be miraculous and inconceivable to her that her work was being shown in the very place she painted it,” said Mary Lowenthal Felstiner, a former professor of history at San Francisco State and author of the astonishing and meticulously-reported 1994 biography of Salomon, To Paint Her Life: Charlotte Salomon in the Nazi Era.

There was almost no information available about Charlotte when Felstiner began researching her. Felstiner, who first saw a book of Charlotte’s paintings while on a trip to Jerusalem in 1975, scoured phone books in the U.S., Europe and Israel to track down Salomon’s few remaining relatives and friends and even learned German so she could better understand her subject. She spent hours digging in archives in Paris and a sleepless night in one of the rooms at the Excelsior in Nice where the local Nazi Kommandant had been quartered.

“The success the Nazis had was so phenomenal that few who lived through it could have imagined at the time that Charlotte’s art would survive, never mind come back home to Nice,” Felstiner told the Daily Beast.

It’s doubtful that most tourists who have come to Nice today for the famed winter Carnival or the brilliant sunshine and piercing blue skies of spring could imagine what took place in the fall of 1943 and winter and spring of 1944 along the city’s broad boulevards and colorful Belle Epoque villas:

Nazis ordered men to pull their pants down in public to show whether they were circumcised or not. Teams of “physiognomists” patrolled the city looking for people with “Jewish” features. Local French residents were encouraged to turn in people they thought were of Jewish descent and the stacks of “denunciation” reports about Jewish neighbors piled up on Nazi desks.

A series of violent raids on homes and in apartment buildings where it was believed Jews were hiding netted thousands who were then brought to the Excelsior Hotel where they were kept under guard before being transported to the Drancy camp near Paris and then to concentration camps in Poland.

As Felstiner points out in her book, the reason why more Jews in the Nice area failed to escape was simple: Getting a visa for the U.S. was almost impossible at the time and the only way out of the region was through the mountains that were heavily guarded and often impassable.

Also, nobody really knew at the time that when the Jews were arrested, they were going to be sent to their deaths. Even when they were sent to Drancy, many thought they were only being sent to labor camps in Poland, not death camps. “There was no precedent for this,” Felstiner said.

Felstiner quotes a historian in her book who notes Brunner’s homicidal reign on the French Riviera “surpassed in horror and brutality everything of this kind previously known, at least in Europe.”

Yet many art critics have pointed out that Salomon was more than just a victim and Holocaust heroine. Her goal, which she made apparent in “Life? Or Theater?” was to break the cycle of suicide in her family and produce one of the most thorough and moving visual records of the Nazi era. In that she was successful.

As she explained in the last image of her work:

“'With dream-awakened eyes she saw all the beauty around her, saw the sea, felt the sun, and knew she had to vanish for a while from the human plane and make every sacrifice in order to create her world anew out of the depths.”