In June 2023, a potentially deadly airborne pathogen known as the Catasat virus began spreading in a small American town called Dewberry Hollow (pop. 100). The symptoms ranged from a light cough at best, to a fever and moderate cough at worst. While the virus puzzled researchers, scientists warned it could put the town’s older residents at risk.

But even younger adults were not immune. Residents like 29-year-old Liza developed symptoms. Instead of going out, she stayed at home and quarantined to reduce the risk of spreading the virus. However, people like 36-year-old Carol chose to go out and continue to earn money to support herself—despite being aware of the virus’ spread.

While the illness continued to come back in waves, the population of Dewberry Hollow was able to flatten the curve of Catasat cases. Eventually, the virus became endemic thanks to the responsiveness of the town’s citizens.

The case of Dewberry Hollow should be familiar to all of us who have lived through the past three years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Of course, there are some differences. For one, the Catasat virus didn’t appear to be as deadly as the coronavirus. The pathogen was also localized in a small town instead of the entire world.

The biggest difference though: The entire scenario was completely made up—a product of the imagination of ChatGPT.

“We coupled an epidemic model with ChatGPT, making them continuously communicate at each time step and for each personified individual in our model,” Ross Williams, a doctoral student in industrial and systems engineering at Virginia Tech, told The Daily Beast in an email. “The novelty is that it offers a totally different way of incorporating human behavior in epidemic models.”

Williams and his colleagues made a preprint version of their study (not yet peer-reviewed) available to read online. For the study, they developed a system that combined an epidemic model with ChatGPT in order to simulate the spread of an illness like COVID-19. The authors argued that such a system offers a unique and innovative way of predicting human behavior—something that they say is a primary challenge with traditional epidemic modeling. The preprint is currently under review.

However, there are a number of concerns surrounding using a chatbot in such a manner—including perennial issues when it comes to AI including bias, hallucination, and accuracy. When it’s used for something as important and impactful as epidemic modeling, the consequences could be dire.

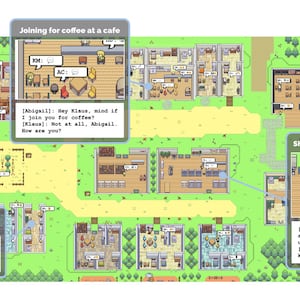

The study itself drew inspiration from Stanford University research that used ChatGPT in order to create “generative agents,” or distinct personas with identities and ambitions that are placed into a fictional town setting. In the Virginia Tech team’s “generative agent-based modeling,” they created 100 different personas with names, ages, personality traits, and a basic biography of their life in the fictional town of Dewberry Hollow.

“We think generative AI has the potential, through generative agent-based models, to provide us with synthetic data on human behavior so policy makers can make more informed choices,” Williams said.

For example, there’s the aforementioned 29-year-old Liza who “likes the town and has friends who also live there.” She “has a job and goes to the office for work everyday,” but later contracted Catasat symptoms including a fever and cough. After reading the newspaper, Liza learned that 4.4 percent of Dewberry Hollow’s population were infected.

The authors prompted ChatGPT with information like the above and simulated how generative agents responded. For example, Liza’s persona opted to stay home and quarantine based on the prompt.

“Liza has a fever and there is a potential epidemic of an unknown deadly virus spreading in the town,” the chatbot responded. “Staying at home will reduce the risk of getting infected and spreading the virus to others.”

The authors conducted three experimental set ups for the citizens of Dewberry Hollow. In the first, the personas were given no additional health-related information like how much the virus is spreading in the town and how Catasat was affecting them. In the second, the personas were given information about their own health—allowing them the ability to self-quarantine if it chose to do so. In the third, the personas were given information about their own health and the town’s growing number of cases.

As you might expect, the first experiment resulted in the epidemic spreading until nearly every citizen of Dewberry Hollow was infected. However, once the personas were informed of their own health situation in the second experiment, there was a sharp decline in generative agents leaving their house and number of overall Catasat cases.

Armed with the full gamut of information and context about the virus, though, the generative agents were able to reduce the number of cases and bend the curve much more quickly than the previous experiments.

“The most surprising moment for us was when the model began to work,” Williams said. “It was just shocking [when] we noted the individuals in our model started staying home as they started coughing or as they heard about the increasing number of cases outside. We never told them they should do that.”

Of course, this might not be a total surprise—especially when you consider that ChatGPT was trained on data up to the year 2021. That would include a sizable chunk of the pandemic. However, Williams argued that it could still provide a fairly accurate picture of how we’d respond to a potential disease outbreak.

“We as humans also take our past experiences to inform our future experiences, so in some ways, having data on COVID-19 data may not be a bad thing,” he said. “Some scholars have already argued that some countries’ better response to the COVID-19 pandemic stems from their previous experiences.”

Williams reasons that ChatGPT essentially fills in a big gap in current epidemiological modeling: human behavior. This is something that’s widely recognized as an issue with tracking the spread of disease—and something that we saw happen with the pandemic.

Humans are complicated creatures, after all. There’s no telling how we’ll respond to things like lockdown orders, vaccination protocols, and quarantine rules. That can be hard for an epidemic model to predict—which is why agent-based modeling can be so crucial.

“[The] lack of accounting for human behavior is arguably the biggest flaw in our current approach to epidemic modeling,” David Dowdy, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University, told The Daily Beast.

While Dowdy praised the inventiveness of the Virginia Tech team’s model, he cautioned that the technology behind large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT aren’t suitable for epidemic modeling—or predicting human behavior. LLMs are language predictors. They’ve been trained on a massive corpus of text for the purpose of predicting the next word in a sequence of words.

While language can tell us a lot about humans, an LLM isn’t designed to predict human behavior. They’re chatbots, designed to produce words and sentences in a human-like manner. Oftentimes, they even fail at doing that.

“For epidemic modeling, in general, we’re looking for things beyond just use of language,” Dowdy explained. He explained that such models are tasked with taking “data on the time and place where people are getting infected with various diseases and then predict where the next disease hotspot is going to happen.

“The amount of data we have on the time and place where people are getting infected with a given disease is orders and orders of magnitude less than the amount of data we have on written language,” he added.

On top of that, there are also the issues that have plagued LLMs like ChatGPT since their inception: bias, racism, sexism, and overall problematic behavior. These issues arise because, as we mentioned, these bots have been trained on text produced by biased humans.

While OpenAI might have attempted to rein in the worst behaviors of its popular chatbot, ChatGPT is not immune to this problematic behavior. Another preprint study released in April found that users could get ChatGPT to espouse hate speech by prompting it to act like a “bad person.” Other LLMs have not fared better, with one bot from Meta claiming erroneously that Stanford University researchers created a functioning “gaydar” to find homosexual people on Facebook.

To their credit, Williams is open about the fact that the team was intentionally vague on the details of the generative agents. They had no clear race, gender, or socioeconomic status. They did the same for the virus, which they gave a fictional name with no clear disease type. “We didn't want to go into too much detail of what composed their persona in fear of biasing the agents,” Williams said.

Dowdy acknowledged that our behavior is—in some ways—determined by our language. Also, the language we use might actually be a solid indicator of where a disease is and where it might spread to. However, an LLM like ChatGPT likely might not be the best tool for modeling an epidemic.

“I think we ascribe a lot to models like ChatGPT because we’re impressed with how well they talk,” he said. “But just because they speak well doesn’t mean they can do other things well. We have to realize what these things are used for. Don’t over-humanize ChatGPT just because it can talk like a human.”

For now, the Virginia Tech team plans to “let the model rest” while focusing on researching generative agent-based modeling for other applications, according to Williams. If there’s anything we’ve learned from the past several years of the pandemic, though, it’s that the more tools that we have at our disposal the better.

However, with the infusion of largely experimental technology like ChatGPT, it might be worthwhile to pause and ask ourselves whether or not this is the right tool for the job—or we might find ourselves in a situation where the cure is worse than the disease.