In a shock verdict in France, International Monetary Fund chief Christine Lagarde, one of the world’s most powerful women, has been convicted of negligence over a $400-million state payout she okayed as finance minister back in 2008.

The decision comes as a surprise just days after the state’s prosecutor had called the evidence against the IMF’s managing director “very weak” and recommended an acquittal. The good news for Lagarde? The court handed down no punishment. And the IMF is keeping her on, citing "the wide respect and trust for her leadership globally" in a statement issued just hours after Monday's verdict.

The case had dogged Lagarde’s entire tenure at the IMF. Indeed, it was already on the table before Lagarde’s whirlwind IMF leadership campaign in 2011 saw her travel 31,000 miles over 12 days rallying support for her cause in Brazil, India, China, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. The lingering litigation didn’t stop Lagarde, 60, from scoring a second five-year term as IMF chief last February, either.

The dispute that would come to be known as the Tapie Affair began in 1993. Bernard Tapie, a businessman and cabinet minister under former Socialist President François Mitterrand, sold the sporting goods giant Adidas that year to a consortium led by Crédit Lyonnais, then a state-owned French bank, for $328 million. The following year, Crédit Lyonnais sold the company again for more than twice the price it paid to Tapie, leading the tycoon to claim he had been swindled.

The disgruntled Tapie sued for damages and saw his case plod through French courts for more than a decade, reportedly costing taxpayers $10 million in legal fees alone.

In 2007, soon after Lagarde was named finance minister under President Nicolas Sarkozy—who was close to the controversial Tapie—she called for the case to go to private arbitration. A year later, the arbitrators found in Tapie’s favor, awarding him over $400 million in public funds as compensation, and leaving Lagarde to decide whether or not to appeal the reward.

Lagarde’s biographers Cyrille Lachèvre and Marie Visot wrote in 2010 that she shut herself away in her office for a full weekend to pore over the case and sound out experts. Ultimately, Lagarde, who made her name as a top-flight corporate lawyer before politics called, decided to let the state’s case rest.

But the court last week noted that contesting the massive reward handed to Tapie could have at least brought to light alleged organized fraud later discovered in the case. Lagarde has not been implicated in that fraud, but six others have been investigated, including Lagarde’s former chief of staff, Tapie himself, and one of the arbitrators who awarded the astronomical compensation.

During her trial last week, in a special court for offenses allegedly committed by serving French cabinet ministers, Lagarde told the court she had been busy with the 2008 financial crisis and that she had considered the arbitration process “not a priority.” She told the court, “the risk of fraud completely escaped me.”

Monday’s ruling appeared to accept the explanation of Lagarde — who returned to Washington before the verdict was read — that she was preoccupied with the global crisis, at least insofar as it gave no penalty at all after convicting her of charges that could have carried a sentence of up to a year in prison and a $15,600 fine.

“The context of the global financial crisis in which Madame Lagarde found herself should be taken into account,” said Martine Ract-Madoux, the case’s lead judge. The ruling ascribed negligence not to Lagarde’s decision to seek a settlement with Tapie, but in not contesting the mammoth reward, leading to the misuse of public funds.

Still, the verdict is a new embarrassment for the IMF and for France. Lagarde’s predecessor, her disgraced compatriot Dominique Strauss-Kahn, stepped down in a letter penned from behind bars on Rikers Island in 2011 after he was accused of violating a Manhattan chambermaid.

Strauss-Kahn’s criminal charges in that case were eventually dropped. As it happens, Strauss-Kahn’s own predecessor as IMF chief, Spain’s Rodrigo Rato, is currently standing trial on misuse-of-funds charges dating back to his tenure as head of a Spanish bank.

It has been a tough run for former French cabinet ministers, too. Earlier this month, Jérôme Cahuzac, Socialist President François Hollande’s former budget minister in charge of fighting tax evasion, was found guilty in a spectacular tax-fraud scandal. Cahuzac was sentenced to three years behind bars, a rare custodial sentence for a French politician.

Indeed, Lagarde’s guilty-but-not-punished verdict isn’t likely to do much to quell French public impatience with politics-as-usual ahead of a presidential election next spring. Hollande has conceded the obvious by not even trying for a second term, while far-right, throw-the-bums-out standard-bearer Marine Le Pen is poised for a trip to the presidential run-off round in May, say pollsters.

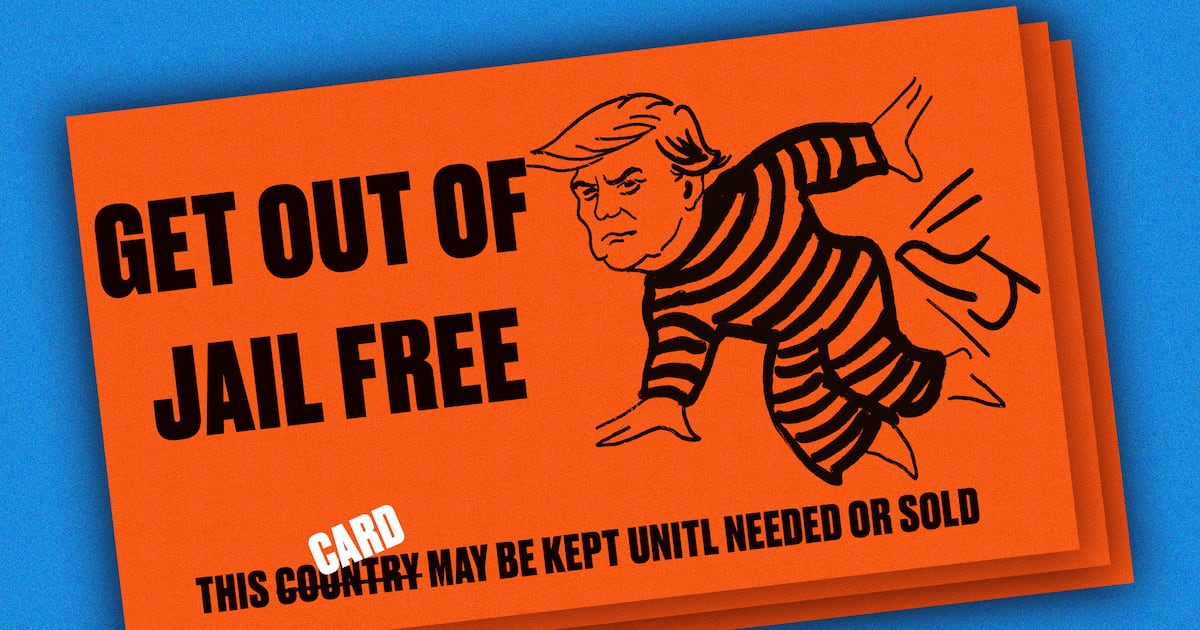

Social media was dripping with sarcastic retorts in French after the verdict. Politicians and regular joes alike took to Twitter to contrast leniency for Lagarde with the fate of lesser folks for lesser losses. Pierre Laurent, the leader of the French Communist Party, caught the zeitgeist, tweeting, “So you can get fired from a cashier’s job for an 85-cent error, but escape punishment for 400 million. #Lagarde #injustice.” You can bet not a few of Laurent’s fellow politicians will look to cash in on Lagarde’s expensive misfortune, too.