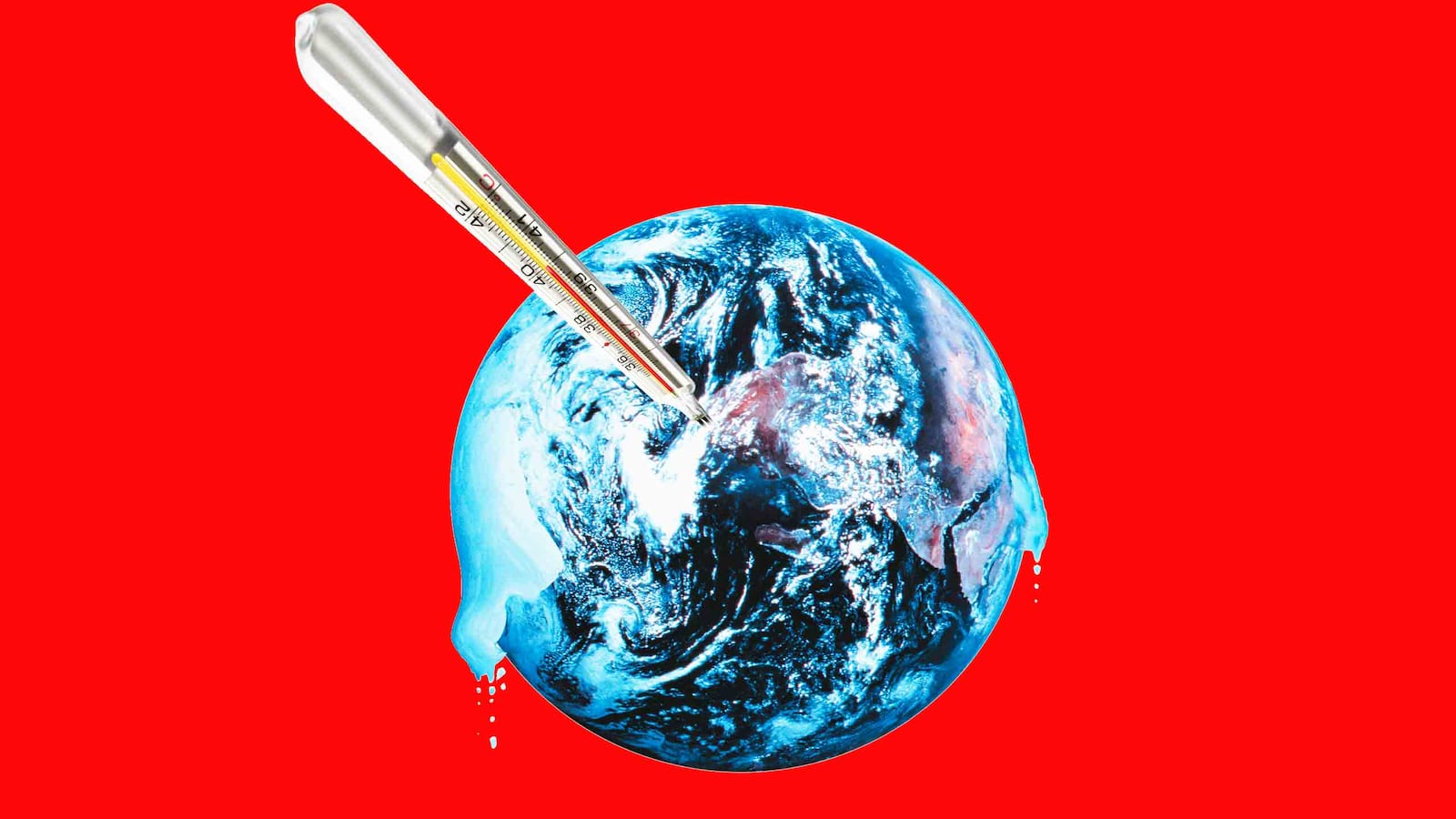

The videos have been devastating: infernal fires threatening Los Angeles like in a Hollywood disaster movie, a starving polar bear collapsing of hunger, “once in a century” hurricanes devastating island after island. Will this finally be enough to persuade Americans to act against climate change?

No.

Americans live in separate mental worlds now. To moderates and liberals, these are obvious signs of global climate disruption—signs predicted, to the detail, by climatic models from the last century. But to those in the Fox News-and-rightward universe, these stories are merely unrelated natural disasters, if they are reported at all.

Are we all just doomed, then?

No, but it will get worse before it gets better.

First, since it is impossible to link any individual storm, drought, or starvation to global climate change—climate change has only increased probabilities, not dictated individual outcomes—the possibility of denial is, it seems, infinite. Every “last straw”—surely, they’ll have to accept reality now, we say—is just another random straw, blowing in the wind.

Second, science is up against a billion-dollar climate-denial industry, a “fake news” machine that existed before fake news was a thing. (No coincidence that the Heartland Institute, one of the most powerful climate-denial front groups, also led Big Tobacco’s fight against the overwhelming scientific consensus that smoking is bad for you.) It’s hard enough to persuade people to do the right thing without billions of dollars’ worth of lies persuading them not to.

Third, the good news is not enough to outweigh the bad. Most climate activists these days take an optimistic approach. Even absent government action, the private sector is leading the way, they note; even WalMart is taking powerful steps to reduce their carbon footprint. States and other countries are stepping in where Trump’s stooges fear to tread. There’s technological innovation all over the place, from Tesla to TerraCycle. And renewables are getting cheaper, while fossil fuels—until the fracking boom, at least—are getting more expensive.

This sunny view is a product of market research, though, not hard science. No one gives money to a hopeless cause—let alone changes their behavior at significant personal cost. If you want people to vote for science-accepting legislators, to buy smaller houses (home heating and air conditioning is usually the single largest contributor to an individual’s carbon footprint), or to support a climate movement, you have to give them hope.

Environmental activists have learned the hard way that “we’re all going to die” is not a good motivator, and so they’ve ditched it in favor of more inspiring messaging.

But good branding is not the same as good science. If you just add up the numbers, there’s no way the bevy of independent, awesome initiatives is going to counterbalance carbon emissions from power plants and cars and fires, methane from agriculture, and the rest. “Think Globally, Act Locally” is a great slogan, but it is ineffective policy.

Fossil fuels, meanwhile, still provide 80 percent of the world’s energy, with trillions of dollars of corporate muscle devoted to extracting every last penny from it. And the same kinds of innovations that improve renewable capacity improve fossil-fuel capacity as well—like fracking.

So, once again, are we all just doomed?

Probably not. But before things get better, they will have to get even worse.

For example, in the near-ish term, poorer coastal areas, like most of Bangladesh, are in serious threat. But richer ones, like New York and San Francisco, will find ways to fend off rising tides, just as Amsterdam and Venice have for centuries. Coastal ecosystems are in grave trouble. Coastal condominiums less so. Big agriculture will adjust; family farms will not. The effects of climate change, like most other things, will vary according to capital.

Tragically, that will translate into lives. The World Health Organization estimates that between 2030-2050, climate change will cause approximately 250,000 deaths every year from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress. But those lives aren’t going to be in places like Paris or San Diego; they will be in developing-world countries with inadequate health care, infrastructure, and money.

Indeed, it’s quite likely that the outstanding progress we’ve made eradicating disease will be nullified by global climate disruption. We’re not all going to die—the richest will live.

Eventually, though, the effects of climate change will trickle up. Maybe it will be ecological disaster that wreaks economic havoc. Maybe it will be a mass refugee crisis, as a billion people flee coastal areas and newly desertified regions, choking cities and straining food supplies. Whatever “it” is, at some point, the vast right-wing conspiracy to lie about climate change will, like Big Tobacco, be humbled.

At that time, it will likely be too late for cutting emissions alone to help. But conveniently, more conservative-friendly climate strategies will be available just as conservatives finally awaken to scientific reality: strategies like carbon removal, geoengineering, and other forms of climate management. These are strategies that even a Republican can love, because they don’t restrict consumption or production. On the contrary, they create jobs.

For example, if you could plant aquatic “forests” of phytoplankton, and they could suck up carbon like a vast rainforest of trees, you could meaningfully move the needle on atmospheric carbon without one coal job being lost. (Yes, of course, that job will be lost anyway due to changing technology, but you get the idea.) That process, using “ocean iron fertilization” to stimulate huge phytoplankton blooms, is already being tested today.

Likewise if you could directly suck carbon dioxide out of the air—a process known as “carbon removal”—and embed it into rockbeds. This technology, too, is already being tested today.

We might even be saved by dust. In one of the more promising geoengineering scenarios, ordinary airplanes could scatter dust particles in the upper atmosphere, simply by flying a bit dirtier than they do now. The dust, in turn, would increase the reflectivity of the upper atmosphere, allowing more energy to be reflected rather than absorbed. The process is known as solar radiation management (SRM).

SRM may sound far-fetched, but it’s happened before. When Mount Pinatubo spewed 17 megatons of ash into the atmosphere in 1991, global warming actually paused for a year and a half. SRM is being studied at the Department of Energy—for now, anyway.

Of course, all of these climate-management techniques involve the risk of unforeseen consequences—also the stuff of Hollywood disaster films. They may work unevenly, or not at all, or too well. They also piss off environmentalists by giving polluters a pass. It’s like putting our planet in the hands of tech bro douchebags.

Which is exactly why climate management will save the world: because it’s the only climate strategy that can appeal to a broad enough constituency and can kick in when all else has failed.

Whether you find that comforting or depressing is up to you.