Welcome to Debunker, a weekly breakdown of misleading (and sometimes flat-out wrong!) news from the worlds of science, health, and more—for Beast Inside members only.

Climate change will suck—but will it suck the same everywhere? One narrative has held that the interior of the U.S. might not be hit so bad, at least compared to the apocalyptic cocktail of hurricanes and flooding heading for the coasts.

But a new paper by scientists at the Environmental Protection Agency pokes some substantial holes in the idea that one could escape all that catastrophe by simply moving to the plains, like staying clear of windows in a house during a violent storm.

In fact, the new study’s authors write that “there are no regions that escape some mix of adverse impacts.”

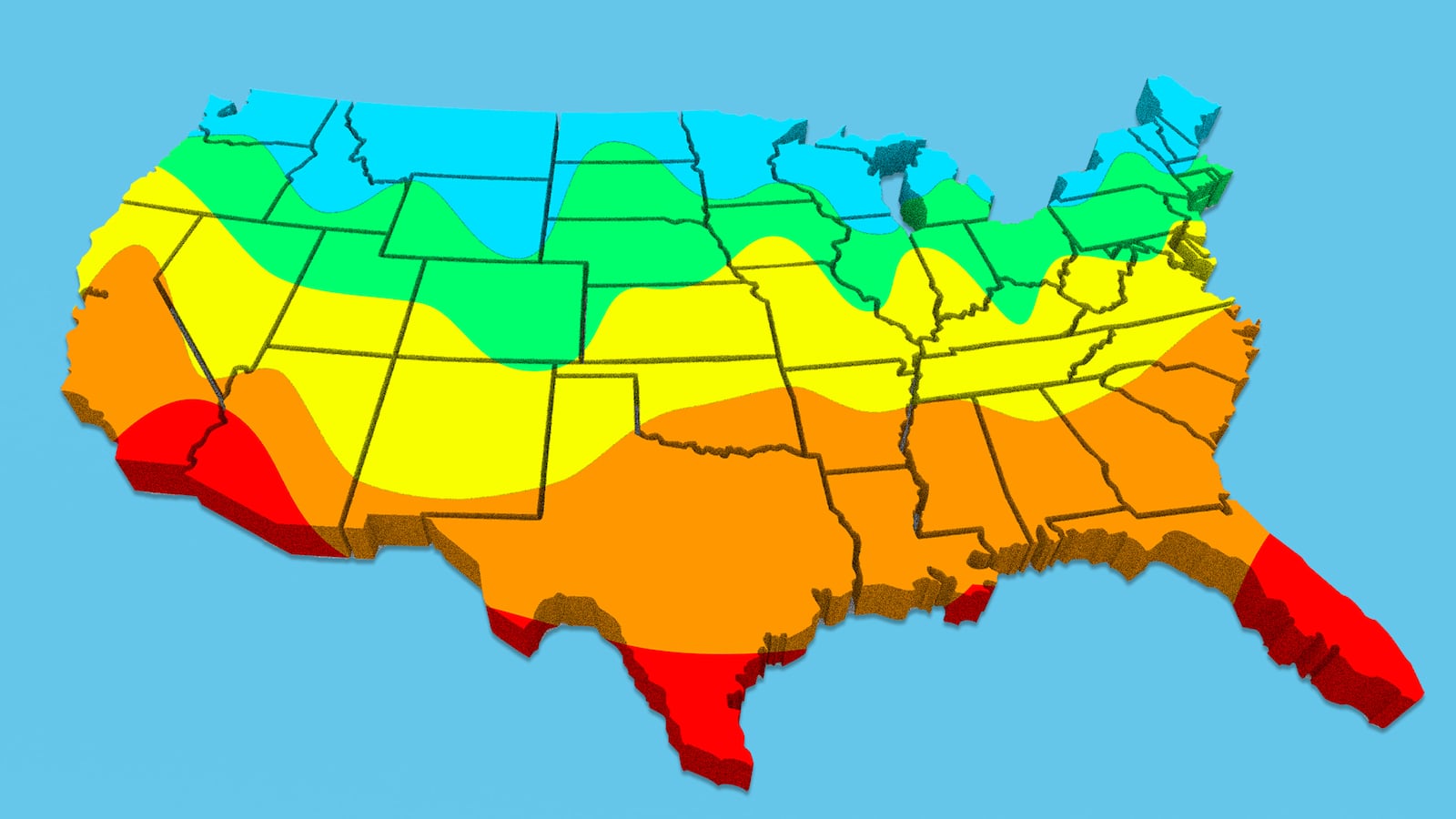

The study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change by EPA scientists Jeremy Martinich and Allison Crimmins, used a complex set of computer models to highlight the physical and economic damages climate change will inflict upon 22 different “sectors,” like air quality, roads and bridges, and coastal property, across varying regions of the country.

The findings are, unsurprisingly, not pretty: In some sectors, a scenario involving largely unchecked climate change would result in hundreds of billions of dollars in annual damage by the end of this century.

The idea that certain parts of the United States might provide some refuge from the coming climate disaster has long wavered between a silly cliché and an actual scientific talking point: Tulsa, Minneapolis, and Pittsburgh have been touted as safe havens. “Cincinnati… is surprisingly good,” one scientist said last year, while another suggested Buffalo and Duluth.

It is easy to understand why. Some of climate change’s most prominent and obvious impacts, natural disasters like hurricanes, wildfires, and sea level rise, don’t really make an appearance in, say, Des Moines.

It gets somewhat more counterintuitive, though, when looking at the regional breakdown of some of these damages. Take air quality, specifically the concentration of ground-level ozone, which can exacerbate asthma and cause other respiratory problems. Under that high emissions scenario, the Midwest and the northern plains will see by far the biggest increases in ozone by 2090, while the Southeast and the West Coast may actually experience reductions. Move away from the rising seas, and find yourself breathing poison.

“Many people have the mistaken impression that the Midwest is not very sensitive to climate change, yet warming impacts in the Midwest are actually substantially larger than many other parts of the globe,” Alan Hamlet, an assistant professor in Notre Dame’s department of civil and environmental engineering and earth sciences, told The Daily Beast in an email. Hamlet has been involved with efforts to assess climate impacts to Indiana, and he said that the Midwest is slated to warm three degrees Fahrenheit more than the projected global average by 2100.

“Counter to common assumptions by the general public, the Midwest is a climate change sensitive region that will likely experience extreme impacts by the end of the 21st century,” Hamlet said.

Those ozone changes seen in the new EPA modeling study have a big impact. In 2090, the Midwest will see 910 excess deaths due to air quality, far more than any other region. The Midwest will also suffer 2,000 more deaths each year due to extreme temperatures, similar to the Southwest and trailing only the Northeast. The region has more bridges that will be vulnerable to climate change’s attendant extreme heat and weather—1,700 of them in 2090—than any other region, will lose more visits for winter recreation than anywhere other than the Northeast, and trails only the Southeast in terms of total economic damages ($46 billion, every year), across all the studied sectors, in 2090. How does Des Moines sound now?

“We tend to focus our attention on the major catastrophic events... in public discourse,” Amir Jina said in an email.

Jina, an assistant professor in the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy Studies, has participated in earlier analyses that modeled out economic damage from climate change.

“That has the unfortunate effect of focusing attention away from the more gradual and less dramatically noticeable impacts, which are typically what you'll see in the Midwest. It's great to see work like this that is contributing to the hard task of adding up the potential impacts not just of the large events but also the more subtle but also sizable pressure from gradual environmental changes and degradation.”

Jina added that he doesn’t find the new results particularly surprising, and stressed that this process of putting numbers to potential damage is key to helping the public understand what is at stake, and maybe push back against that idea of gaps in the catastrophe map. And perhaps equally importantly, the study puts some numbers to the potential benefits of actually confronting the problem.

For example, a scenario involving substantial emissions reductions would reduce the number of severe inland river floods by half, which could save almost $4 billion every year. Other sectors represent even greater opportunities: the avoided deaths due to extreme temperatures represent a savings of $82 billion per year, and work hours saved with a stronger climate policy add up to $75 billion. That air quality problem that will plague the Midwest? Reducing emissions dramatically could cut $8 billion per year off of that particular price tag.

And while Jina is encouraged by this sort of accounting, some experts think we’re still not accurately projecting climate change’s impacts. Michael Mann, a professor of atmospheric science at Penn State and author of several books about climate change and climate change denial, notes that some of the economic damages in the new study arise due to extreme weather events—and it may underestimate just how bad these might get.

He said that his and his colleagues’ own work has shown that the climate models currently in use may be failing to incorporate some important inputs that will exacerbate storms and other extreme events as the climate continues to warm.

“In that sense, studies like this one if anything actually underestimate the impact that climate change is having on these events,” Mann told The Daily Beast via email. That might mean that the damage projections on things like coastal property—or, to head back to the Midwest, inland flooding—could be even higher than we expect.

In their paper, Martinich and Crimmins stress that these sorts of studies still need improvement, in the form of additional sectors and improved modeling capabilities, to better understand what’s coming down the road. But the study, from which “a complex geographic pattern of damages emerges,” should probably put to bed the idea that there are some secret hideaways where climate change won’t reach.