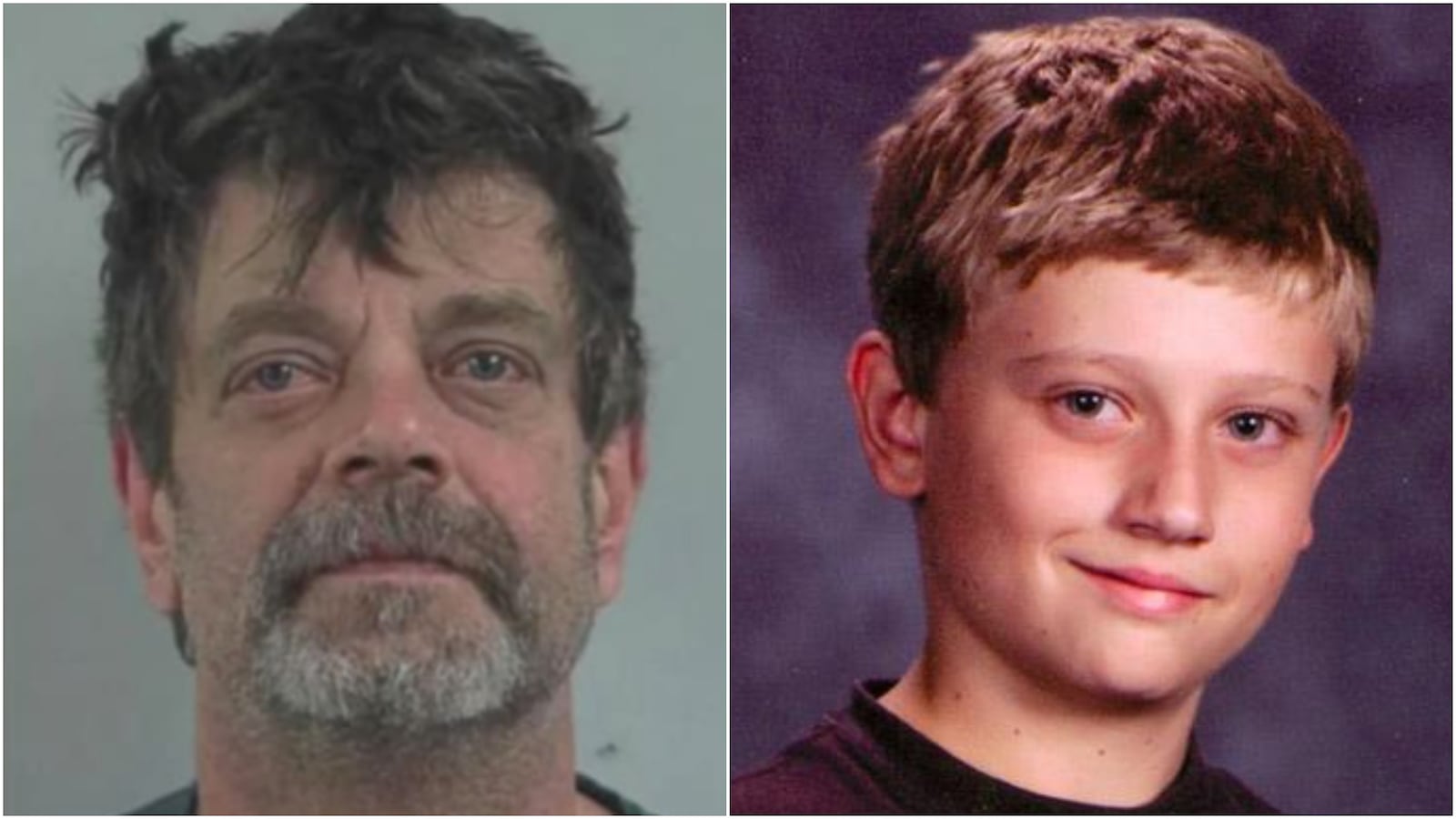

After six-and-a-half hours of deliberations, a Colorado jury on Friday found Mark Redwine guilty of second-degree murder for killing his 13-year-old son Dylan in a fit of rage after the boy found photos of Redwine wearing a red bra and eating feces from a diaper.

Redwine appeared next to his lawyers in court Friday wearing a black shirt and a gray tie, but no jacket. He awaited the verdict with his hands folded, and showed no emotion as it was read out. His lawyers, John Moran and Justin Bogan, did not immediately respond to a request for comment on Friday.

Redwine’s trial on murder and child abuse charges began in mid-June, after years of delays and two mistrials.

Dylan Redwine was last seen alive on Nov. 18, 2012. He had arrived in Durango, Colorado for a court-ordered visit with his father, amid a contentious custody battle between Mark and his ex-wife Elaine Redwine.

Dylan and Mark, 59, had “argued and fought” the last time the boy was there, states a 2017 indictment charging Mark Redwine with murder. Dylan didn’t want to stay with Mark, and asked a friend if he could sleep over at his house—a “request that was denied by Mark Redwine,” according to the indictment.

That evening, Dylan made plans to meet a friend the next day. He never showed up.

Mark Redwine, 59, reported Dylan missing, but investigators didn’t buy it.

“Dylan Redwine’s blood was found in multiple locations of Mark Redwine’s living room, including on the couch, the floor in front of the couch, the corner of the coffee table, on the floor beneath a rug, and a love seat,” the indictment states.

“DNA testing showed that Dylan Redwine was the source of the blood on the love seat, and could not be eliminated as a contributor to the mixture found in the blood found on the couch, floor in front of the couch, the corner of the coffee table, and the blood found beneath the rug.”

Redwine’s girlfriend at the time explained this by claiming Dylan had cut his finger and bled in the living room, about a year before he disappeared.

In June 2013, a cadaver dog located Dylan’s partial remains off an ATV trail less than 10 miles from Mark’s home. During a subsequent police search of the house, a sniffer dog picked up “the presence of cadaver scent in various locations in the home,” and on the clothing Mark was wearing the day Dylan vanished, the indictment states. Two more years passed before Dylan’s skull was discovered by hikers, about 1.5 miles from where the rest of his remains were found.

Mark’s defense team contended that Dylan was likely attacked by a bear or a mountain lion. However, Redwine was seen driving an ATV down the same road where Dylan’s remains would be discovered, days before a search party was due to look for the boy’s body. And a forensic examination found blunt-force trauma to Dylan’s skull, as well as a fracture above the boy’s left eye—injuries experts testified likely were inflicted by another human, not an animal.

Prosecutors argued that Mark Redwine was the only person with a motive to kill Dylan. They alleged he decapitated his son in an attempt to get rid of evidence that could link the boy’s injuries back to him.

The indictment said that Mark had previously “reacted violently” when Dylan’s older brother Cory challenged Redwine about “compromising photos” in early 2012. The filing also cited a police interview with Redwine’s ex-wife, Betsy Horvath, who said Redwine had told her that “if he ever had to get rid of a body, he would leave it out in the mountains.” She repeated the claim on the stand during Redwine’s trial, during which Redwine’s son from a previous marriage took the stand. Among other things, Mark Redwine hadn’t been particularly interested in helping searchers look for Dylan’s body, Brandon Redwine, Dylan’s half-brother, testified earlier this month.

“I figured Mark knows something,” Brandon told the courtroom. “I didn't know what he knew, I didn’t know how he knew it.”

Redwine appeared on the “Dr. Phil” show in 2013 to deny any involvement in Dylan’s death. He will remain in custody until sentencing, which is scheduled for Oct. 8.