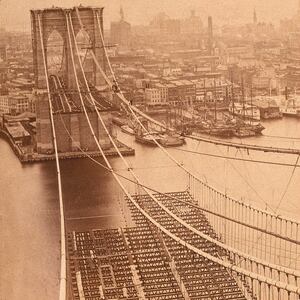

On May 30, 1883, tragedy struck the Brooklyn Bridge six days after the project hailed as the Eighth Wonder of the World had officially opened. It was a holiday in the city, so crowds of residents with leisure time on their hands decided to check out the new bridge for themselves.

For 14 years, they had watched hundreds of workers slowly assemble the first great connector between Manhattan and Brooklyn. The result was the longest suspension bridge in the world, and the first to use steel-wire cables. It was a river-spanning feat of engineering like nothing ever seen before, and everyone was a little on edge about whether or not it would all come tumbling into the East River.

As locals pushed their way through the masses that Wednesday, one woman fell down some stairs. She screamed, which caused others near her to panic and set off a domino effect. A full stampede was narrowly avoided, but not before 12 people were killed in the rush of the crowd.

“Somebody shouted out that there was danger. And the impression prevailed that the bridge was giving way beneath the crowd,” the New York Sun reported.

This impression was baseless, but if one man hadn’t been quite so diligent as the bridge was being constructed, it might not have been so. As a result of just one of the corruption scandals that plagued the Brooklyn Bridge, faulty steel was threaded through the cables holding everything up.

Luckily, the potentially deadly steel fraud was caught and adjustments were made so that the subpar materials didn’t threaten the structural integrity. Nearly 140 years later, the Brooklyn Bridge is still one of the main thoroughfares between the two boroughs. And that weak steel is still stretched along its cables.

“If you receive a bid from a Mr. Haigh of South Brooklyn, it will be well for you to investigate a little”

On Dec. 4, 1876, J. Lloyd Haigh was one of nine people to submit bids to supply steel for the massive new public works project being constructed in New York City. Washington Roebling, the project’s chief engineer, was not happy about it. The decision was out of his hands—responsibility for awarding these lucrative contracts rested with the board of trustees—but Roebling did what he could to warn them that Haigh was not a man to be trusted.

“If you receive a bid from a Mr. Haigh of South Brooklyn, it will be well for you to investigate a little,” he wrote to them in a letter that was maybe a bit too polite.

For his own part, Roebling was a paragon of virtue. Despite the fact that corruption had seeped its way into the Brooklyn Bridge project—the infamous political macher Boss Tweed was happy to help smooth its way after receiving $60,000 cash and $47,600 worth of shares—the family responsible for the design and construction of the bridge had kept their hands spotless.

Washington Augustus Roebling, 1883.

Universal History Archive/GettyRoebling’s father, John A., was the visionary and brains behind much of the bridge’s design. After he died in 1869 following a foot injury, his son Washington took over.

Nearly 30 years before the Brooklyn Bridge project began, the pater Roebling had opened a steel mill under the unwieldy name of John A. Roebling’s Sons Company. The mill produced quality product, and Roebling wanted to make sure that it had a fair and unblemished opportunity to compete for the big new contract. So, he did what others in his position so often haven’t done: he completely divested from the company.

Despite the fact that Roebling had cut all financial ties with his family’s former steel mill, there were still some whispers that favoritism was at work when the trustees awarded the company one of the contracts. But no one blinked when the second contract was given to Haigh against the chief engineer’s warnings.

Later, it would come to light that the problems with Haigh went far deeper than his own shady business practices: future mayor of New York City and current bridge trustee, Abram Hewitt, owned the mortgage on Haigh’s mill and had put his thumb on the scale to look after his own financial interests.

After the trustees made their decision, the chief engineer had no choice but to work with Haigh, but he never stopped being on high alert. And for good reason. From the very start, Haigh had no intention of honestly filling the order.

For most contracts, the bridge sent inspectors to check the materials being delivered every so often. But for materials coming from Haigh’s mill, Roebling instructed his inspectors to check every single roll of steel being sent to the bridge. He also warned them that the man in charge would probably offer them a bribe to look the other way.

Construction of a tower of the Brooklyn Bridge. 1875-1878

GettyRoebling was right. Haigh tried to send subpar steel to the bridge. The inspectors discovered the problem and sent those pieces back. Haigh tried to bribe the inspectors, but they turned him down and told their boss.

One can imagine the conversations had between Roebling and his inspectors. Here they were trying to pull off one of the greatest engineering feats in the world—who did this guy think he was?

During this time, Haigh was the recipient of the first phone line for commercial use in the city in a twist of historical irony that demonstrated the acute need for the bridge that he was diligently trying to undermine. Haigh’s Steel Company had offices in both Brooklyn and Manhattan and, according to the Brooklyn Eagle, he “found it irksome to send messengers trotting back and forth” between the two, a trip that was long given that there was no direct route across the river. So, he was able to get a phone line strung “along the uncompleted skeleton of the bridge.”

In the meantime, the bridge authorities couldn’t do anything about Haigh’s steel contract, but they could continue to collect evidence against him and diligently check every shipment. They thought they had taken all proper precautions to thwart his shenanigans, but in late July 1878, they realized they hadn’t gone far enough.

A crowd stands on the early foundations of the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, September 21, 1872.

Hulton Archive/GettyWhen faulty steel was discovered in the shipments, the inspectors would reject it and order Haigh to put it in a discard pile. One day, one of the inspectors noticed that, while steel continued to be rejected, the pile holding the condemned pieces wasn’t growing any larger.

They soon found that, after a wagonload of steel was issued a certificate of approval, Haigh would have it make an extra stop at the location where the faulty steel was being held. The loads would be switched out, and the bad steel would be delivered to the bridge worksite with the certificate saying it had passed inspection. The good steel would then be returned to Haigh’s mill, where it would be loaded onto a wagon and the whole process would begin again.

By the time this scheme was discovered, Roebling “estimated that as much as 221 tons of rejected wire had been spun into the cables,” according to Structure Magazine. It was too late to remove it.

Roebling quickly informed the board of trustees about what was going on. “The responsibility of any weakness that may be found in the cables rests with the old board of trustees, because they awarded so important a contract as the cable wire to a man who had no standing, commercially or otherwise, and the same responsibility must be assumed by the present board if they fail to at once put an end to Mr. Haigh’s contract,” he wrote to them.

But the board was terrified about the optics. According to David McCullough in The Great Bridge, the local press had been questioning “in big headlines whether the bridge was a failure.” Boss Tweed had died earlier that year and the corruption that pervaded the city was now being uncovered and condemned. They were worried about what another scandal would do to the project. So… they chose to do nothing.

They ordered Roebling to continue the contract with Haigh and they suppressed the information.

Today, the throngs of pedestrians and cars who travel over the East River daily can do so with every feeling of safety because Roebling, once again, saved the day.

Redundancy had been built into the cables—they were six times as strong as they needed to be. With the faulty wires, it was estimated that they were now only five times as strong. But that wasn’t good enough for the man in charge. Roebling decided to add 150 additional wires to each cable, and told Haigh that he would supply each of them of good, sound quality free of charge.

In the end, Haigh went down, but not for his egregious behavior on the project that would become one of the iconic sights of the city. His company was mired in financial troubles, for which he was eventually put in jail. And what was in part responsible for the downturn of Haigh’s business? The financial drain of having over $200,000 of bad steel left on his hands.