Personality-driven docuseries like Tiger King, The Way Down, and Bad Vegan are, to a large extent, the offspring of early-2000s freak-show reality TV, and that relationship is once again highlighted by Dangerous Breed: Crime. Cons. Cats. The three-part nonfiction venture (Nov. 22 on Peacock) was born out of Frederick Kroetsch’s decade-long attempt to turn amateur pro wrestler Teddy Hart into a small-screen star. While that effort went for naught, it did give Kroetsch access to a wild individual who bred Persian cats, engaged in polyamory, smoked tons of weed, and was charged with sexual assault—all before his wrestling-trainee girlfriend Samantha Fiddler went missing shortly after entering his orbit. It’s a tabloid-y tale of sex, drugs, and violence, and one that Kroetsch rightfully views as an indictment of himself and the tawdry genre that helped facilitate its horrors.

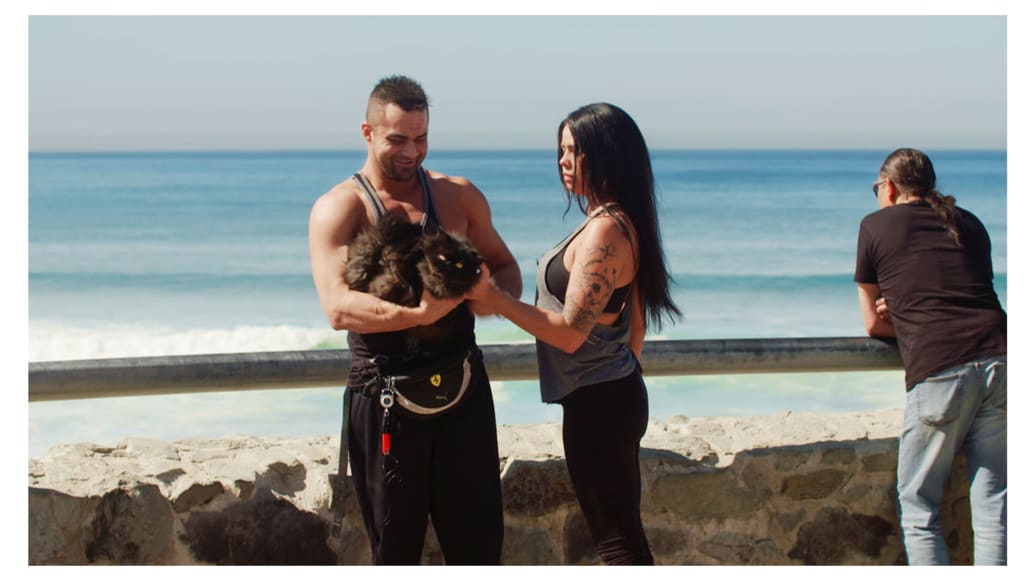

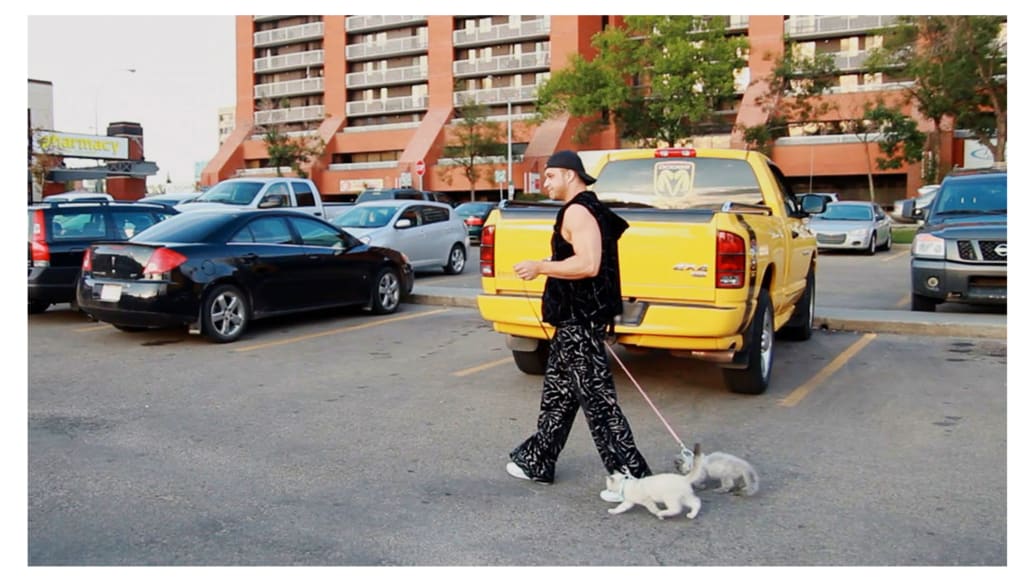

Samantha’s disappearance, which remains unsolved to this day, is the central focus of Dangerous Breed: Crime. Cons. Cats., although it can only be understood within the context of Kroetsch’s 2012 decision—as a fledgling Edmonton filmmaker in search of a gripping story—to check out the local amateur independent wrestling scene. That’s where he met Hart, a member of a legendary wrestling clan that included Bret “The Hitman” Hart, Jim “The Anvil” Neidhart, and Davey Boy Smith, aka “The British Bulldog.” The first time Kroetsch visited Hart, he knew he had a potential ratings bonanza on his hands, given that the athlete resided in a house decorated with marijuana posters and populated by Hart’s partner Faye and girlfriend Michelle, as well as by anywhere from 50 to 100 Persian cats that he bred, sold, and juggled. With a blunt always in hand, Hart was a train wreck who was tailor-made for trash TV.

Though he hailed from pro wrestling royalty, Hart was on the skids by the time Kroetsch hooked up with him, thanks to a history of being a difficult, unmanageable loose cannon. Dangerous Breed: Crime. Cons. Cats. establishes his in-ring skills and manic, narcissistic demeanor through a combination of archival clips from his wrestling past and from Kroetsch’s initial reality-TV footage, upon which the director frequently comments in hindsight.

To package and sell his material, Kroetsch took various tacks, first emphasizing Hart’s cat obsession and, later, his swinger lifestyle. Yet a real angle emerged when, after two and a half years of filming, and on the verge of finally signing a broadcast contract, Hart was accused of sexual assault, physical assault, and illegal confinement by Faye and Michelle, who in a subsequent interview detail the methods of domination and control that Hart used against them, from stealing their passports and holding them hostage to choking and raping them.

Peacock

Hart promptly fled to Dallas and professed his innocence to Kroetsch, who—eager to have his work pay off with a TV deal—went along with what his subject was selling and kept the cameras rolling. In the U.S., Hart moved in with aspiring wrestler Machiko, who in a clip is seen being threatened with abuse outside a Japanese restaurant (“You’re on borrowed fucking time”). In return for keeping the show alive, Kroetsch convinced Hart to return to Edmonton to face Faye and Michelle’s charges, and when Hart kept up his end of the bargain, he was promptly arrested, while Machiko was busted for an outstanding warrant and his beloved Persian cat Mr. Magic was deported over a paperwork issue. Within days, however, Hart was free on bail (thanks to shady acquaintance Bill Kazoleas) and was grooming Samantha, a stripper and single mother of three, to be his latest wrestling protégée and paramour.

Kroetsch admits to not being particularly proud of these decisions, both because of what he suspected about Hart and because his presence—and the promise of fame and fortune—is what drew women to the wrestler and encouraged and enabled his bad behavior. For all the director’s regret and self-recrimination, Dangerous Breed: Crime. Cons. Cats. doesn’t go the extra step and point a finger at itself as a continuation of such filmmaking exploitation, but its relative self-awareness is nonetheless refreshing. Kroetsch is correct in positing himself as an active, influential contributor to the saga he was recording. And his sense of culpability helps transform these proceedings into a case study of the inevitable effect that documentarians have on the stories they tell, and thus a refutation of the idea of detached non-fiction impartiality.

It’s also a portrait of an unhinged creep who lives up to Faye’s description as “one of the worst men on the planet.” That becomes apparent once Hart got involved with Samantha and convinced her to relocate—without her three kids—to Orlando to train at Team Vision Dojo, a school whose owner Chasyn Rance is a registered sex offender (for crimes against minors) and the producer (along with Hart) of wrestling fetish videos. Before long, Hart bailed on Samantha, and the evidence on display strongly suggests that he stole her Canadian passport and left her to her own devices as a veritable illegal immigrant in Florida. There, after a few months of working as a landscaper (and, possibly, exotic dancer), she dropped off the radar, never to be seen or heard from again—thereby initiating a frantic, futile search by her sister April and friend Jayme, among others.

Peacock

Kroetsch confronts Hart about Samantha in 2021 but only comes away with denials, evasions, and egotistical woe-is-me complaints. Despite his numerous lies, it seems probable that Hart didn’t directly have anything to do with Samantha’s disappearance. Still, Kroetsch persuasively contends that Hart’s decision to disempower and abandon Samantha in a foreign country with no means of supporting herself or returning home was a major factor in her mysterious fate. For this, Kroetsch feels a measure of guilt, since—as with everyone in Hart’s orbit—Samantha probably stuck around the wrestler because he appeared to afford her a shot at a better life, thanks in part to his promising reality TV program.

Dangerous Breed: Crime. Cons. Cats. doesn’t go so far as to blame Kroetsch more than Hart for this sorry state of affairs. Yet at its best, it does recognize the toxicity of not only “outrageous” entertainment-industry individuals but, also, the shows that make them notorious stars.