David Duchovny Turned Down Scientology, Doesn’t Care About UFOs, and Loves Making Sweet Music

Ekaterina Gerbey

The actor, novelist and musician opens up about his new album “Gestureland,” why “Californication” couldn’t be made today, and telling Xenu to f*ck off.

The fifth episode of The Chair, Netflix’s critically-acclaimed series about the minefield that is modern-day academia, sees Professor Ji-Yoon Kim (Sandra Oh), the freshly minted chair of the English department at Pembroke University, pay a visit to the home of actor David Duchovny. You see, in a bid to juice enrollment, the university decided to go over Ji-Yoon’s head and give their Distinguished Lectureship post to Duchovny, and she’s determined to talk him out of it.

After drinking in a red Speedo-clad Duchovny—a nod to that infamous X-Files scene—and some haggling over the pronunciation of the word “prescient,” he disappears into a far-away room in his mansion. When she finds him, Duchovny is seated on a build, strumming at the guitar, and singing a tender song.

You have a good voice, she mumbles.

And you know what? She’s right. It’s evident on his new album Gestureland (out now), particularly via songs like “Call Me When You Land” and “Tessera.” It is evident that, unlike the Russell Crowes of the world, music has become more than a passing hobby for the former X-Files and Twin Peaks star—this is his third LP after all—but a genuine passion. The past few years have also stirred Duchovny to be outspoken politically for the first time in his life, as on his tune “Layin’ on the Tracks,” where he lambastes the “stupid orange man in a cheap red hat.”

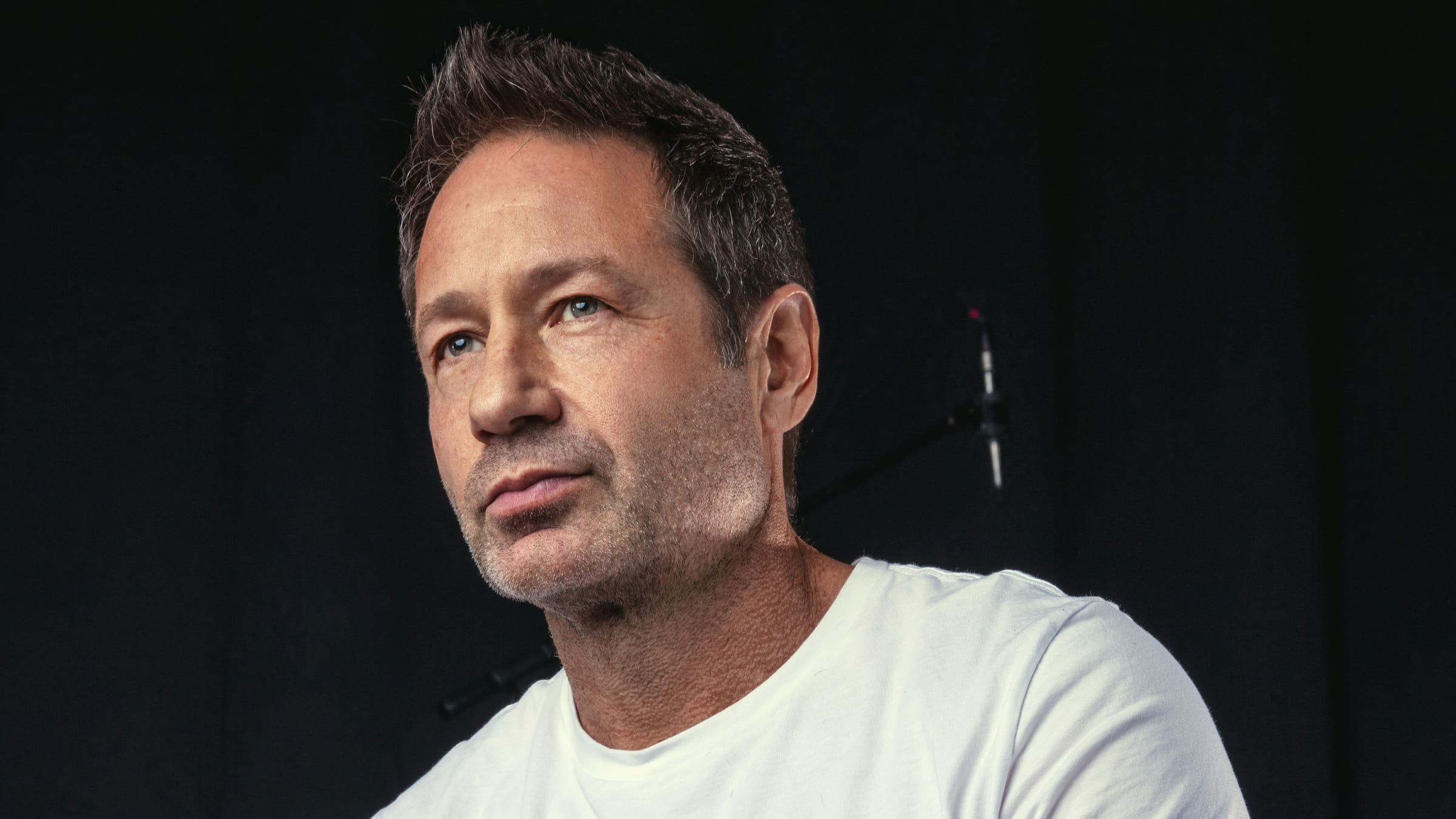

In a wide-ranging talk from his home in California, Duchovny—sporting about three days of stubble—spoke about the making of Gestureland, what it felt like to lose one of his best friends to Scientology, how Californication has aged, and why everyone should get vaccinated: “You do the right thing, and you get to become a citizen of the world and not a citizen of your screen.”

Before we get to the album and everything, it’s been an insane year and a half. I’m curious how the pandemic has altered your perspective on things, since we all spent a lot of time with ourselves.

These world-shaping events—9/11, COVID-19—that affect the entire globe, they tend to make us say, “Oh, we’re going to change now. We know now that it’s about love, it’s about family, it’s about connection.” And we do that for a while, and then we go back to whatever colder, default position we were in. I guess that’s what I was looking at, because I was locked down with my son, which is a great thing to have for a father, but it’s not so great for a 16, 17-year-old boy. There’s no world where that would happen except for this one. That got me thinking, “The world went to hell, everybody’s suffering, people are dying, and yet I’ve been forced into this deeper connection with this person that means so much to me. Can I hold onto that once I let him go? Is that what life is about? Is life about holding onto it, or is life about letting go of it?” That’s all the shit I was going through.

And I read that you got COVID, so you know how bad it is. Is it therefore infuriating for you to see people who are just refusing to even get vaccinated or wear masks?

It’s infuriating because it’s really about generosity. If I’m wearing a mask, it’s protecting you more than it’s protecting me. I’m protecting you more against my aerosols than I’m getting from yours, so it’s really a way of saying, “I care about you, let’s get through this.” Vaccination is the same. It’s not just taking care of myself; it’s making sure that I’m not going to be carrying it and giving it to other people. The fact that this has been politicized to such a degree—it feels impossible to untangle. It’s a real moral failure on the part of politicians and people. It’s the most cynical thing I can think of. It’s not even, “I got it so I’m angry,” it’s that we could be almost done with this. We could have done so much better.

Your new album Gestureland isn’t really a “pandemic” album, so to speak.

It’s not the Bo Burnham show.

Exactly. I’m curious how this album took shape, because you started it in Feb. 2020, right before the pandemic hit.

We were far along in recording—we had the demos—so obviously none of these songs were written during the pandemic, but they were produced during it. What you realize is that everything that comes out now you see through the lens of the pandemic. It’s just the major lens we have now, and I think if songs are strong enough, they can get reinterpreted. I think the best songs take on new meaning depending on what’s going on.

So, you wrote a song like “Everything Is Noise” prior to the pandemic? Because listening to it now, when you sing about “running away from death” and trying to break free from the constant hum of chaos and noise, it seems very timely.

That was before, but you’re right: I think we have to come to terms with the fact that we’ve all gone a little crazy. We think we’re the same, but a year is a long time to change your behavior that drastically. And I think that’s kind of what the people that don’t want to wear masks—underneath the craziness of it, the illogicalness of it, and that stupid fucking, “We’re Americans, you don’t tell us what to do—I think that underneath that is this sense of, “I just want to recognize myself. When I look in the mirror, I don’t want to see this person anymore that I’ve been for the last year.” So, I get it, man. We’ve all gone a little crazy. We’re all having trouble recognizing ourselves, literally and figuratively. I want it to be done too, bro! But it ain’t. So be smart, do the right thing, and don’t be an asshole.

I’m curious, do you think a show like Californication could get made today?

The short answer is “no,” and the long answer is, “If you really watched the show closely, yes.” But that’s never going to happen. You’re never going to get past the bells and whistles of it to get to the heart of it, and to see that it’s actually on the side of the things that we think are good now. But it’s done in such a tonally-discordant-to-our-time-now way, that I think people would just throw up their hands immediately and say, “Turn it off!”

David Duchovny performs on stage during the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival at Public Hotel on April 22, 2018, in New York City.

Steven Ferdman/Getty

I don’t think people would be able to move past the first few episodes, when you talk about him having sex with a 16-year-old girl…

Oh yeah, sure. Exactly. And politically, I agree with it; but artistically, if nobody is actually getting hurt, anything is fair game. What are you saying? Does your story have merit? Does it have artistic merit? Does it have storytelling merit? I don’t judge actions politically and artistically the same way, and yet I don’t think we’re in a culture now that distinguishes.

I do art should be a space to examine troubled people and disturbing behavior, and that it doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re co-signing these actions.

No, not at all. But that is a funny thing. When you’re forced to talk about what you do when you’re creating stuff, people ask you what you’re saying. So, first of all, what I say I’m saying doesn’t matter—and if I did it successfully is up to you guys to figure out. If I wanted to say it, I would’ve said it. The reason why I wrote it as a song, or wrote it as a novel, or acted it, is because I couldn’t say it. It’s more complicated than that. And now, it seems like we want our art to say something really straightforward and simple. And that’s OK, because that’s where we’re at. But if you can say in an interview what you’re trying to say in an artwork, I’m going to think that it’s probably not that good.

You do have an anti-Trump song on the album, “Layin’ on the Tracks,” and almost any act of celebrity protest is sort of met with an eyeroll these days—especially during the Trump years, where Trump assumed the bullshit role of this anti-elite populist, which therefore made it even more difficult for famous folks to come out and say stuff. But what compelled you to write it?

It was kind of cobbled together. I think we mashed together two or three songs to make that song; and at one point, we just felt we should lean into the political stuff. I’d never written anything like that or was even that into politics until the Trump years—and then I became obsessed, and then during lockdown I was like, “Dammit, I’m watching Chris Hayes and Rachel Maddow every single night. This is going a little crazy.” I really liked, “Stupid orange man in the cheap red hat.” I know it’s not clever, but I just thought, keep it in. And a lot of the other lyrics were more introspective, and it was about my failures. It wasn’t about Trump’s failures or his followers’ failures. At one point I say, “The part of me that turned away I have to kill, I have to bury the chain, because your suffering is my shame, it’s my suffering.” So, I’m addressing my own selfishness and my own apolitical-ness. But I was aware that if you hear a song with the line, “Stupid orange man in a cheap red hat,” you’re not going to win anybody over. It’s just name-calling. It’s not sophisticated political debate. It was just anger at that point—and disbelief. I’m still in disbelief.

There’s this idea that people in Hollywood should shut the fuck up and not speak up when it comes to politics, and I’ve always thought that’s pretty silly, because not only are there people from all over the world in Hollywood who work different-paying jobs, but there are a lot of smart people there. You went to Princeton and Yale, and I know where you went to school is whatever, but it seems ridiculous to think that you’re therefore not entitled to a political opinion because you’ve attained a certain level of fame or because you act.

I agree with you—but I also disagree with you. I will play Devil’s advocate here, because it’s kind of what I would say when I wouldn’t express my political opinions, because I didn’t for a long time. The first thing I would say is that, similar to what I was saying with art and politics, politics is not nuanced. And I’m not necessarily good at that. I’m good at nuance. I want everyone to get a vaccination. That’s not nuanced. And yet, if I sat here and went, “Oh, maybe they’re afraid or this or that,” that has no business going out in public. If you’re going to be a politician, you’ve gotta be hard. Obama tried his best to be nuanced, and whenever he tried it he got fucking killed. My nature is nuance, so I’m not going to win in that area—plus they’re going to attack me personally, and it’s going to hurt. I don’t need all that stuff. Having said that, yeah, my opinions are fine. Sure. They could be worthwhile for some people. But the idea that anyone would change their minds because I had a certain opinion? I wouldn’t want that. That’s not what I’m going for. In a song like “Layin’ on the Tracks,” I’m trying to create a mood that puts a little at this guy’s doorstep, but also says it’s part of yours too, listener, and mine too, writer.

Now, to go to the other part where I disagree with you, which is that famous people should not speak out, is this: I think that the whole Citizens United stuff—that’s the debacle of campaigning, that the Supreme Court equated money with free speech. Like, I can give as much money wherever I want because it’s the same as my words. It’s putting your money where your mouth is, literally. It’s perverted our politics. And celebrity is a different kind of currency. So, if I’m a celebrity—and I’m not a big social-media guy, and the highest part of my being a famous person is pre-2012, so I don’t have as many followers as whoever the fuck—but you have to conceive of that as money; you have to conceive of that as a donation. When a celebrity gives an endorsement, it’s worth something.

David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson in The X-Files

FOX

Sort of like these sponsored Instagram or social media posts.

That’s right. So that was always my reason. I thought, “I know who I’m voting for”—and this is before now, when I wasn’t as angry—so my saying it out loud to influence other people, why should I exercise that power? Why is it legal that I should be able to exercise my voice? It’s one person, one vote, but it’s not one voice, one voice. This one voice has more power than this other voice, so to me, it seemed like gaming the system. And that’s not what I wanted to do. It felt like a donation, and it felt like money. I don’t know. Or maybe I was just lazy and didn’t want the hassle.

One show you did that I really love is Twin Peaks. And with Denise Bryson, you’re connected to this trailblazing transgender character. I’m curious what you and David Lynch were trying to accomplish with Denise? Because the series came out at a time when there was a lot of transphobia in media, in films like The Silence of the Lambs, that portrayed transgender people as psychotic serial killers. So, to have this self-possessed, virtuous transgender DEA agent seemed to fly against that ugliness.

I couldn’t tell you what David was thinking, but I could tell you what I thought about the character and what I was told going in. What I was told was that Mark Frost, who was co-writing the series with David, is good friends with James Spader, and Spader had come up with this idea of a Drug Enforcement Agent who went undercover in women’s clothes and then decided that that was the way they wanted to live. So, Mark wrote it, and then Spader got busy, so they had to recast it. I was a struggling actor desperate to get jobs, so I got a call to do this audition from Johanna Ray, who was this casting director who was always trying to cast me in stuff and a big supporter of mine, and somehow, I got it. You know what? I never thought about anything political or sexual; I just approached it the way I approach anything I do. I had to figure out how to make it real to myself so that it felt real on the outside. So, I thought, “What is human in me that would want those human things that that person is doing? What is the expressiveness through those clothes, or through that affect, that I can relate to?”

Denise Bryson (David Duchovny) on Twin Peaks

ABC

The key to it wasn’t the clothes for me, it was seeing that bar scene. Men kind of hang back and keep a neutral face in a conversation and are maybe nodding, and there was a feminine energy that was much more present—and maybe that’s a cliché or a gross generalization, but that was my way in. Everything this person did opened them up, and they just felt good. That’s the way I went at it. And so many years later, I got to do it again [in The Return]. And in the current climate, I couldn’t even audition for it now if I wasn’t closer to that person. David [Lynch] has this great line in this one scene I did with him as an actor, and he talks about how he went to bat for me, and he says, “I told that clown car that they had to fix their hearts or die.” And I thought, “That’s the line of the year.” I just was in love with that line. And for me, that’s what the whole role became. It’s not about a political statement of any kind—it’s fix your hearts or die, people. It’s forgiveness, love, and empathy. This is where we’re at. Fix your hearts or die.

I’ve reported a lot on Scientology and did a story on your good friend Jason Beghe, and how he stood up to the Church of Scientology. I’m curious what it was like for you to lose one of your best friends to Scientology? I’ve never lost a close friend of mine to a cult, so I can’t imagine what that must have been like. And did they ever try to recruit you?

Well, Jason and I drifted apart during that time, because Scientology hangs with their own when they’re doing it. We’d see each other from time to time, and I noticed that his vocabulary was different. The way he described the world and his experiences, particularly his psychological experiences, was cult-ish and had changed completely. Either I didn’t have the balls to slap him and snap him out of it, or he said it was working for him, or… maybe I failed him as a friend during those years? I did go to his wedding at the Celebrity Centre in Los Angeles, and they made a play for me. I did squeeze the cans and I did a session on the E-meter, and I realized immediately, because they’re asking very personal questions, that they were gathering information that I didn’t want to give out to a stranger. So, the session didn’t go well. I didn’t play by the rule, and I never went back. And Jason, to his credit, never tried to recruit me. He only “recruited” me in the sense of saying, “This is great, and I think you should try it,” not anything harder than that.

You dodged a pretty big psychological and financial bullet. They drain people dry.

They really do. And that’s another thing—the tax code. I don’t really understand it. It’s a “religion,” but who figured that out? There are other religions that are tax-exempt that have a lot of wealthy people in them as well, so it’s really a question of taxes and religions, but it’s also a question of: How do you define yourself as a religion? Why can’t I be my own religion of one and stop paying taxes? I think that’s what Jeff Bezos is up to!

I’m also a fan of The X-Files. How frustrating has it been for you to constantly be asked about UFOs in recent years?

It’s not as bad as it used to be. It kind of ticked up with the recent revelations—or non-revelations. But I never connected to it with any kind of intensity on a personal level—it was my job to appear that way—nor did my involvement with the show cause me to have any greater interest in it than I did. For me, it was more like a religion and that’s how I played it. I would’ve acted that way if he was a Scientologist. This was a fanatic, in a way. Rationally, I get that people associate me with that, so I don’t get super frustrated. I just wish I was more interested, because I’m not that fascinated with it. I have to say though, when I was a kid, I was super fascinated with it. I loved Chariots of the Gods? and when I was 11, I saw that movie and was really into that shit. But somewhere along the way, I lost it and never got it back.

In addition to The X-Files, I grew up a fan of The Simpsons, and “The Springfield Files” is an all-time-great episode. One of my favorite scenes in it is where you’re working out Homer on the treadmill, and you ask, “What’s the point of this test?” and Scully says, “Oh, I just thought he could stand to lose a little weight.”

[Laughs] I have no recollection of that! I should watch it. All I remember is the ID with me and the Speedo. But yeah, it was just such a busy, busy time. I’m sure we were shooting a season of the show and at some point, we both said yes to doing The Simpsons—which I didn’t really watch. Obviously, I was aware of it and had seen some, but I wasn’t a huge watcher of the show. At the time, I probably felt like, “Oh, fuck. I’ve just gotten off work and now I’ve gotta go and record these scenes.” I didn’t know it was gonna last longer than anything and be important to people.

I wanted to go back to Californication for a sec. I know you went to rehab at the time [for sex addiction] and did the character of Hank Moody have a strong effect on you? Because it is this libertine, freewheeling character that you were inhabiting.

No… Nah… No. To me, doing that job was just pure fun, and working with those actors to make that particular brand of funny was really what I wanted to do at that point, because I’d gotten off The X-Files and thought, “I want to do movies,” and the kinds of comedies I wanted to do weren’t coming my way, and then this came along. I thought I’d never do TV again and then cable started doing these 12-episode years, and I thought, “Oh, this is very doable as a lifestyle.” I could never do 25 hours again. I can’t do that. But 12 half-hours? Yeah, I can do that. But Californication was a lovely set to be on, working with Natasha [McElhone], Evan [Handler], and Pam [Adlon], so no, I can’t point fingers anywhere.