In some East Asian cultures, during a child’s first birthday shindig, parents and celebrants crowd together in an endearing fortune-telling practice to predict the direction of their professional lives. The baby, in traditional clothing, sits in front of a table with different objects in front of them—a pencil, a string, a book, a stethoscope—each denoting a career path or life trajectory to which they might be energetically drawn. In Korea, the practice is called doljabi. And in Netflix’s new academic dramedy show The Chair, a depiction of doljabi for a rather anonymous baby in the fifth episode holds the show’s central thesis: as pure as intentions may be, the game has somehow become fixed.

The scene doesn’t feature the main character, Dr. Ji-Yoon Kim (played by Sandra Oh), the titular chair of the English department and first of her background in a fictional college called Pembroke. Rather, her adopted daughter Ju Ju (Everly Carganilla) and spiraling white love interest, Bill (Jay Duplass), attend the doljanchi (first birthday) and act as spectators to the thrilling doljabi. On the table sit a stethoscope, a string (indicating, as Ju Ju notes, a long life), a paint brush, a pencil (representing education), and a dollar. The baby hesitates, confused, watching the adults cajole her toward one object or another. Her hand touches the brush and a smile creeps along Bill’s scruffy, unkempt face. (Having dealt with his own troubles at the university, it stands to reason he’d love for this child to choose a different path.) But a woman in red nudges the single American dollar forward, right into the child’s field of vision, and the baby ends up choosing it. Bill, in the midst of a cultural practice that firmly places him on the outside, starts to lose it, claiming that she “rigged” the game. He goes full-on white man and lunges for the dollar, enraged and held back by family members who only know him as Dr. Kim’s disheveled dick appointment. In all the tumult, the assortment of drugs he’s been popping to keep his lid on comes tumbling out of his jacket and onto the table. In a flash of horror, the baby almost grabs a pill before a relative scoops her up.

So yeah, shit hits the fan rather quickly, but it could’ve been a lot worse. Which also seems to speak to the rationale of continuing to push in a game that ultimately feels fixed for certain people’s failure. The Chair is interested in the psychology of marginalized people who choose to press forward in an academic culture that was built on their exploitation. Even if one sits as department chair, they’ll ultimately eat the shit of largely white male counterparts.

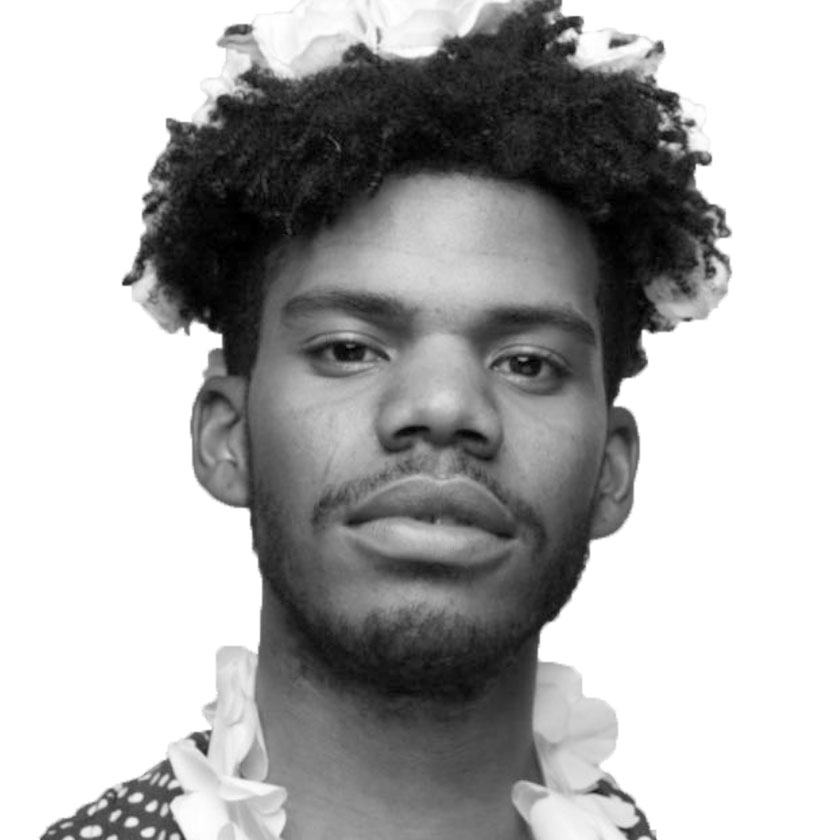

The moment that Dr. Kim gets the position, she is pressured by the dean (David Morse) to push out the oldest, least popular members of the faculty: an unnamed narcoleptic (Ron Crawford), her friend Prof. Joan Hambling (Holland Taylor), and Prof. Elliot Rentz (Bob Balaban), each holding on to tenure for their dear, geriatric lives. Rentz opposes the promotion of a young Black professor, Yaz McKay (Nana Mensah), whose innovative pedagogy proves threatening to the suffocatingly white-ass teaching methods of the others. Kim is caught at a crossroads as she desperately wants to promote Prof. McKay to a distinguished position but also save face with the elders who actually hold power in the department.

The power struggle here between Kim and the department reflects one academics may recognize time and again: the difference between having a title and actual influence. It’s clear to Prof. McKay, to Bill, and even to her adopted child that despite the promotion, Kim is still impotent against white dominance. No one actually listens to her. Bill certainly doesn’t, not even after a number of spectacular fuck-ups including accidentally projecting a photo of his late wife in labor to his entire class and joking about Nazism in a room full of always-online students. Her daughter Ju Ju doesn’t either; she runs away from home and disrespects Kim at every turn, even while, rightfully, clocking her for not being motivated to be close or intimate with her. That lack of intimacy is packed with a certain kind of shame around Kim’s mothering, in what feels like a cycle of guilt that is only amplified by her new gig.

There is clearly a lot going on but Amanda Peet and Annie Wyman’s half-hour series handles the plot with arresting efficiency. There is no fluff, no wasted air time; it demands your eyes up from your phone to catch all the jokes and subtle meanings. There are lessons on the ways racism, sexism, ageism, and consumerism have all seeped into scholarship, but it never feels like a lecture. Nor does it fall into the trap of being anti-intellectual or, as some folks would term it, “anti-woke.” The show is careful not to disparage young people who, yes, can be reactionary but often because they can smell bullshit from a mile away. The students stage a march and protest against Bill, and that does turn into a back-and-forth that seems to lose the plot a little. But those students also form the moral center of the entire show. They realize that the only real power they have is as a collective and they exercise that power by signing petitions to save ethnic studies and ensuring the work of Prof. McKay is respected and rewarded by the English department.

As a moral compass, the students’ posturing can come across a bit showy—as is the case when Prof. Kim conducts a seminar discussing Audre Lorde’s famous essay on the master’s tools’ inherent inability to dismantle the master’s house. Still, the scene shows her that the impotency she feels in this fucked-up system is intentional, and purposeful. Either get in line using the tools to further their exploits or get gone.

It doesn’t matter what her aims were stepping into the new position, Prof. Kim was always going to lose unless she shed parts of herself—her care for the powerless, the indelible purpose of her teaching dogma—but The Chair makes the narrativizing of this lesson so incredibly fun and worth it that we almost can’t help ourselves in playing along and rooting for her to win. The game is the game, after all.